There are crimes committed every day by those who know, and ignore, the law. Not huge crimes, admittedly, because we’re talking about the laws of thermodynamics in this case. But the urge to find a way to create something from nothing, to have some quantity of power multiplied into more and more ad infinitum without any continued effort, is an ancient human desire that has appeared regularly throughout history–before the laws were even defined.

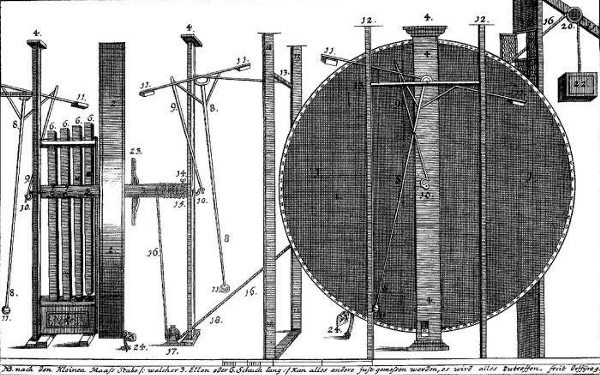

Take Orffyreus–the pseudonym of German inventor Johann Bessler, whose claims to have built a perpetual motion machine made him the talk of Europe’s universities during the 1710s and 20s. What Orffyreus constructed was a series of large, hollow, wooden wheels covered in cloth with pulleys and weights attached; giving them a small shove made them accelerate faster and faster, until they settled at about 26 revolutions per minute. Orffyreus seemed so confident that he had discovered a way to turn gravity into free power that he called his 1719 pamphlet explaining how the wheels worked “The Triumphant Orffyrean Perpetual Motion”.

The inventor’s most infamous demonstration came in 1721, when a group of learned men from across Europe received an invitation to Weissenstein Castle in the capital city of Hesse-Kassel–one of the many nations that made up the patchwork Holy Roman Empire. Orffyrean had been at the castle for several years working on his machines at the duke’s request, and was to showcase a 12-foot-wide wheel to the esteemed guests. For some time he had been building bigger and bigger versions of his perpetual motion wheels, and gaining powerful fans in the process. (Peter the Great had even inquired about purchasing one.) This wasn’t the first famous test, either: A few years earlier, in 1718, one wheel had been allegedly sealed in a room alone and was found still spinning when the door was unlocked two weeks later.

At this latest demonstration, the men present tried to stop the wheel from turning–and, as others had experienced in the past, they were nearly taken airborne with its force. It seemed to all in attendance like a wheel that would spin forever, one that could be used to power any device without need for feeding or refueling. Talk turned to money. Surely, they began to think, there was a way to get rich from this thing? Orffyrean wanted £20,000 [roughly £2.75 million today, or nearly $4 million] to spill the secret of his perpetual motion wheels; the men considered raising the funds from investors in London and forming a company to sell the wheels for use in agriculture and industry.

But things took a turn when the Dutch mathematician Willem ‘s Gravesande started poking around under a suspiciously placed cloth; furious, Orffyreus smashed the machine, claiming the professor was attempting to steal his work. Shortly afterward, a maid came forward and admitted she had been paid to turn the wheel from outside the room with a secret crank. The name Orffyreus quickly became an 18th-century synonym for huckster in newspapers and academies throughout Europe.

(As a side note, ‘s Gravesande didn’t let Orffyreus’s obfuscation dissuade him from believing that gravity was a source of infinite energy–he even tried to enlist Isaac Newton as an investor in the London company there had been talk of forming. The lure of perpetual motion was strong, even in the sharpest minds.)

I found the story of Orffyreus in a piece Simon Schaffer wrote for the British Journal for the History of Science in 1995. In it he argues that we shouldn’t condemn the people of the time for failing to recognize the difference between those wooden wheels and, say, a Newcomen steam engine–which was also on display in Hesse-Kassel in 1721. After all, this was an age when the modern concept of science was still being invented, and alchemy was still a respected field of study–it made as much sense then that the force which makes things fall to the ground could be turned into rotational power, just as steam could. There was also a natural skepticism among many people that the intellectual inventions of philosophy and mathematics had any usefulness for the more practical miner or farmer. Schaffer writes:

The story of perpetual motion [was not] a mere illustration of the inevitable and principled establishment of the equipoise of social prudence against popular delusion and baroque fantasy “¦ Engines such as those shown at Weissenstein were to be used to drive fountains in the prince’s parks, pump water from the state mines, model the ordered cosmos, save the cost of teams of laborers and raise funds from well-heeled financiers.

So, as you watch the videos below–taking a virtual stroll through history to see what perpetual motion looked like to our ancestors–don’t judge the believers too harshly. Once upon a time a battery would have looked just as magical as a wooden wheel covered in cloth and rope.

1. Bhāskara’s wheel (c.1150)

Quite where the idea of an unbalanced wheel first appeared is unclear: There are hundreds of examples throughout history, but the earliest well-documented one was invented by the Indian mathematician and astronomer Bhāskara II, who lived in Bijapur, Karnataka, during the 12th century.

This is a modern version seen above, but the premise is the same as Bhāskara’s. While mercury was his preferred liquid to fill the hollow tubes around the edges (rather than water, as shown), the motion of either liquid is enough to “push” the wheel slowly around. Eventually, though, friction on the central axis will always stop the rotation. It doesn’t matter if the unbalancing effect comes from a liquid, weights on rotating arms, or magnets.

(Note: I found references to an earlier version of this that used magnets, built in 8th-century Bavaria–but no primary source. It is unclear if there is any truth to the story.)

2. Boyle’s flask (c.1660)

Noting that capillary action will draw water up a narrow tube, many people have attempted to create a self-filling flask–whereby a reservoir empties at its bottom into a tube, which then empties out into the top of the reservoir.

This type of setup is usually called Boyle’s flask after Robert Boyle, the influential English chemist who also once proposed such a device. Too bad it doesn’t work. The siphon force only causes the water in the tube to reach the same height as the water in the reservoir, while capillary action will raise it just a few centimeters more. In the video above, it works with beer because of the energy from the escaping carbon-dioxide bubbles–but as soon as the beer goes flat, it’ll stop.

3. The self-filling water mill (c.1480)

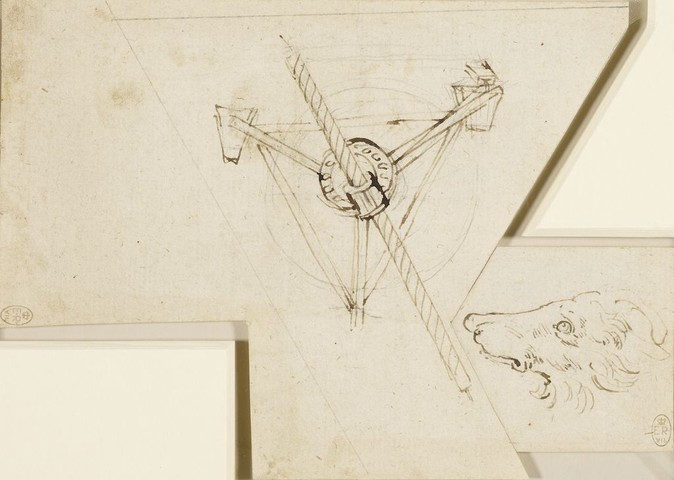

This might be attributable to Leonardo da Vinci, but the idea of a mill that uses a closed loop of water–instead of a river or other replenishable water source–appears multiple times in history. It’s based on the concept that falling water turns a wheel, which powers some kind of system for raising the water back above the wheel (often, an Archimedean screw).

Below is da Vinci’s interpretation from circa 1480; it’s one of several sketches he made of machines like this (he was also a designer of unbalanced wheels).

Even more so than the previous two, it should be obvious why this won’t work. Even if you stop the water from evaporating, the energy required to turn all of the components in a self-replenishing system means it would quickly stop moving from the build-up of water at the bottom.

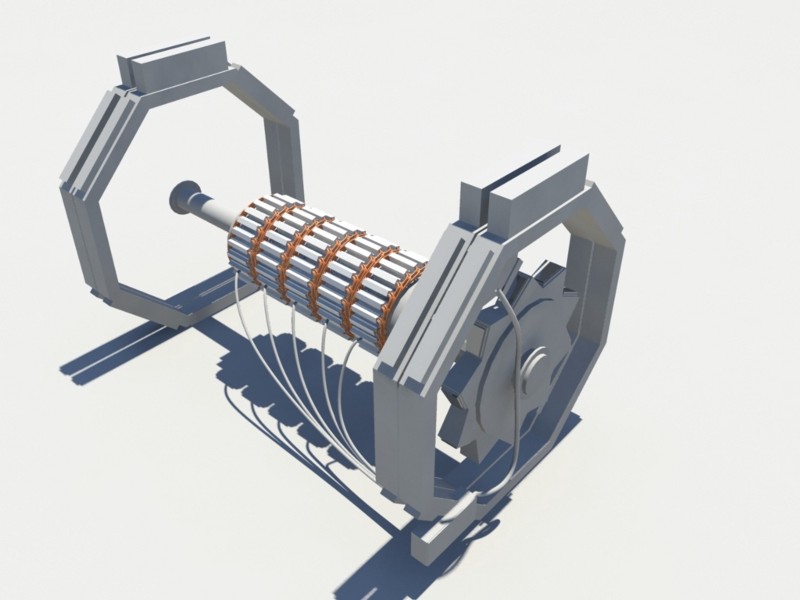

4. Newman’s motor (1979)

It’s a DC motor–that’s it. But inventor Joseph Newman claims to this day that his motor produces more energy than it requires to turn over, so it can recharge the batteries that power it as it runs. (The U.S. Patent Office disagreed, repeatedly.)

There’s still a healthy community of advocates for Newman’s motor online, as, indeed, there is for almost any kind of perpetual motion machine. Many people who rally around the idea that governments and big corporations don’t want us to have free energy do so because they are politically motivated by a desire for self-sufficiency and autonomy.

5. Self-Sustaining Electrical Turbine Generator (2014)

Here’s just one example of the risks of trusting everything you read on crowdfunding sites–this project, seeking to “use existing hardware technology to generate electrically based energy as-needed by using innate gravitational forces,” only raised $128 of its $10,000 goal thanks to widespread condemnation of its clearly nonsensical science.

Sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo don’t have rules barring projects that break the laws of physics, so perpetual motion machines continue to appear online. However, none so far seem to have persuaded enough people to part with their money to being “production.”

6. Steorn’s Orbo (2016)

Dublin firm Steorn claims to have discovered a “magnetic anomaly”–which enables the pulling of power out of thin air–while working on power supplies for boilers several years ago. To its credit, Steorn doesn’t say it’s invented a perpetual motion machine–just that it stuck some metals together using a chemical of indeterminate nature and a current came out the other side, and that their best guess is that the energy is coming from ambient radio waves.

Steorn is even selling phone chargers under the “Orbo” brand name, and you can find its employees performing field demonstrations in bars and pubs.

If you’d prefer not to spend 1200 euro [$1,355] on one, and instead want to know what it actually is, there’s a group of Finnish scientists crowdfunding to buy a couple and take them apart (as well as make a documentary in the process).

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Power Up section, which looks at the future of electricity and energy. Click the logo to read more.