On the slopes of the seven hills that surround the city of Medellín in Colombia, life is pretty good. Children play in the streets. Retirees relax in the parks. Workers bustle to and fro as street vendors hawk arepas–maize pancakes topped with cheese, avocado, and more. When I visited the “City of Eternal Spring” in 2014, named for its year-round balmy temperatures, I found its steep residential neighborhoods filled with spaces for art and theater, verdant parks, schools, and public libraries.

It hasn’t been this way very long. In the 1980s and 1990s, Medellín was the most dangerous city in the world. An urban war involving multiple drug cartels, including the Medellín Cartel led by Pablo Escobar, spiked the city’s homicide rate to more than 800 per 100,000 people in 1993. In barrios like Santo Domingo, which were largely built by refugees from the surrounding countryside, crime was a daily fact of life–and police that tried to intervene paid with their lives.

But today the city’s homicide rate sits around 20 per 100,000, far lower than cities like New Orleans and St. Louis. According to Numbeo’s quality of life index, which takes into account factors like life expectancy, crime rate, purchasing power, healthcare, and more, the city ranks alongside New York City, Turin, and Doha. What changed?

The answer glides silently overhead. In 2004, the city’s then-mayor, Sergio Fajardo, cut the ribbon on a scheme that must have seemed ridiculous at the time: a cable car, running from Santo Domingo down to the metro line that snakes through the center of the city. What use was a ski lift in a place where the temperature has never dropped below 46°F (8°C)?

But, local politicians argued, the idea made a great deal of sense. The steep sides of the Medellín valley make traditional rail transit impossible. Buses get stuck in the city’s perpetual traffic jams, resulting in a commute to the center that takes at least two hours–each way. A cable car, its growing crowd of supporters said, would let the population of Santo Domingo soar over the dense, irregular neighborhoods below, reaching their destinations in minutes, not hours. It would let them become a real part of the city.

“I grew up with an idea of fear, of danger, of exclusion of those areas,” says Pablo Alvarez Correa, a Medellín local who offers free walking tours of the city, describing his first ride on the cable car. “I decided to go when a friend came to visit me from abroad. It was absolutely amazing. It was very interesting to be able to see the state of development of those areas; to understand that many things had improved for them.”

Those improvements were quantified in a 2012 research paper published in the American Journal of Epidemiology. A team of U.S. and Colombian researchers compared violence in city neighborhoods that had access to the new cable car with similar areas that didn’t, both before and after it was built. “The decline in the homicide rate was 66 percent greater in [cable car] neighborhoods than in control neighborhoods,” they wrote, “and resident reports of violence decreased 75 percent more in [cable car] neighborhoods. These results show that interventions in neighborhood physical infrastructure can reduce violence.”

Correa concurs that these areas are much safer than they had been previously, noting that the cable car project marked the beginning of greater investment in these previously neglected areas of the city. “The cable car brought the library, and then next to the library they built a little park, and then they built an entrepreneurship center where they empower people from the community to get access to credit or to get coaching in some idea that they had,” he explains.

“Then because tourism started, someone said, “‘Maybe we can start selling street food in these areas where the tourists go by.’ It’s not only about the cable car and that’s it, but it is using it as an excuse or as part of a program to bring many other services.”

Today, the cable car system in the city has been dramatically expanded. Line K, the original line that connected the metro system with the neighborhoods of Acevedo, Andalucía, Popular, and Santo Domingo, was joined by line J in 2008, and line H in December of 2016. A more tourist-oriented line L opened in 2010.

“Before, those areas with the cable car were extremely dangerous, and now they have become the jewel of the crown of Medellín” says Correa. “Now they are very proud because that’s where people come to visit.”

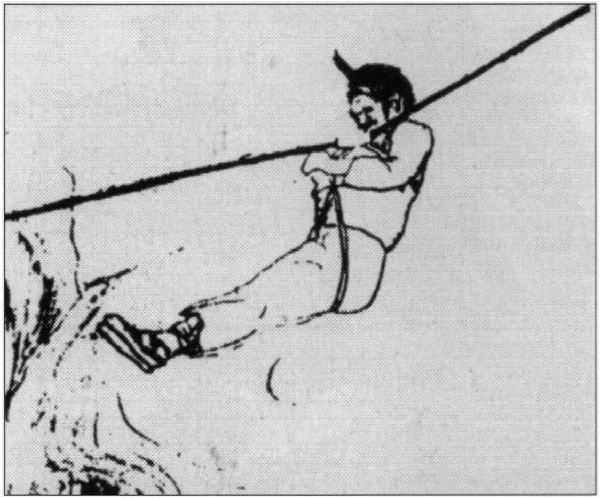

No one knows who invented the first cable-propelled transit system. Its origins are lost in the mists of time, and the technology was almost certainly developed independently in several locations to solve local problems. The first records of people transported by cable-drawn systems go all the way back to a brush drawing of a ropeway (below, centre) in South China in 250 B.C.

Researching the topic can be difficult, primarily because there are seemingly hundreds of different ways to refer to slight variations on the same basic principle. Spend 10 minutes looking into the subject and you’ll find people talking about gondolas, aerial tramways, ropeways, cableways, téléphériques, funiculars, funitels, inclined lifts, and many more.

“That is actually one of the fundamental research problems that people encounter with the technology,” says urban planning consultant Steven Dale, founder of online cable car resource The Gondola Project, who has dedicated his career to the topic. “The blanket term we use for all the technologies collectively is “‘cable-propelled transit systems’: any system that is supported and propelled by a cable,” he adds.

“There’s probably about a dozen different sub-branches, and those are things like an aerial tram or a jigback, or a pulse, or a mono cable, or a bi-cable. The word gondola is specific to the cabin, but it’s become a kind of catchall term to be used for the system as a whole, particularly in North America. Cable car is another catchall term. It actually technically refers to a very specific type of cable-propelled transit system, but it is so commonly used that we stopped fighting that battle a couple of years ago. We realized it was a pointless battle to fight.”

Cable cars (which I’ll try to stick with for the duration of this article) are very good at solving a specific but increasingly common problem–how to transport cargo or people across topographical obstacles. “Remember topographical doesn’t just mean natural–it can mean man-made as well,” says Dale. “We see all sorts of problems where there’s a 12-lane highway between point A and point B, or there’s an industrial park, or there’s some man-made piece of topography that creates a barrier to access.”

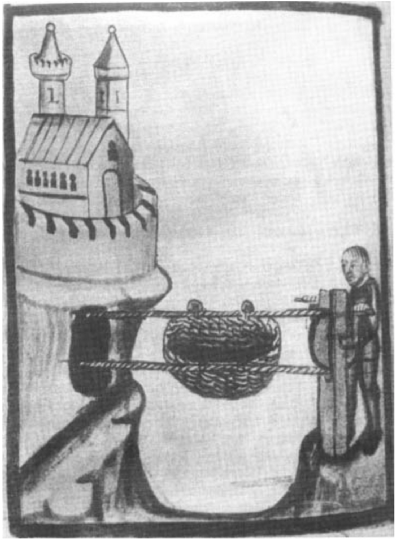

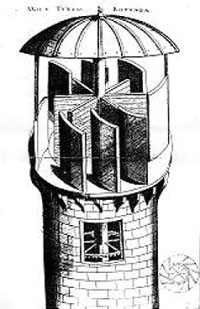

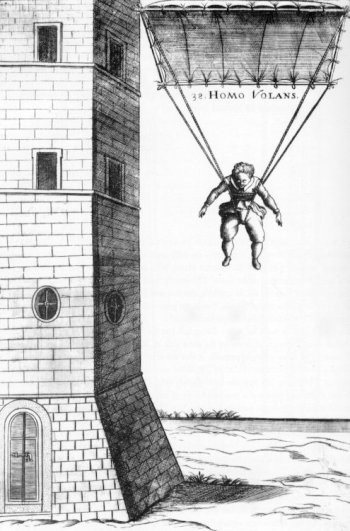

That’s exactly the problem that a Croatian bishop named Fausto Veranzio faced in 1616. One of the earliest urbanists, the Pope had called him to Italy to help deal with the frequent flooding of the Tiber River, which he solved with an ingenious water regulation system. While in Italy, Veranzio wrote and published a book called Machinae Novae, which depicted 56 different inventions, machines, devices, and technical concepts.

Inspired by the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci a century earlier, his inventions included several types of mill, a universal clock, wind turbines, a parachute, suspension bridges, and, most interestingly for us here, an aerial lift that crossed the river on multiple ropes. The drawings earned him a global reputation and were so popular that they were even reprinted in Chinese a few years later.

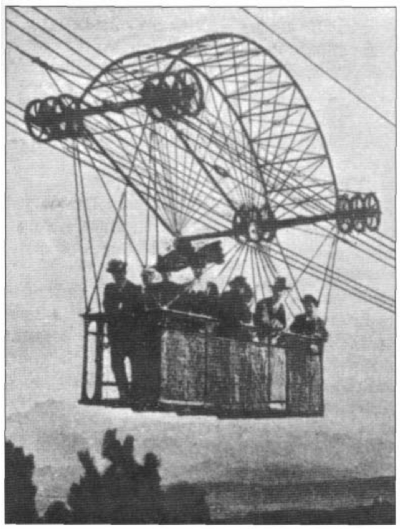

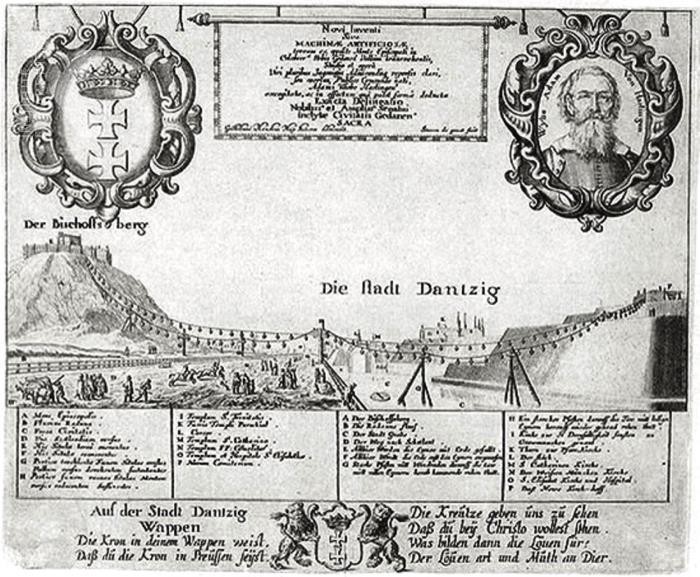

Not long afterwards, in 1644, a Dutch engineer named Adam Wybe was given the task of figuring out how to move large amounts of soil over the MotÅ‚awa River in GdaÅ„sk, Poland, to construct defensive fortifications. His solution was to build the world’s first modern cable car.

The machine was supported by seven wooden pylons, some 650 feet [200 meters] long, and inspired by existing ropeways. But Wybe nonetheless chalked off some significant firsts. He was the first to use a looped cable (as opposed to a rope), the first to put multiple vehicles on the same cable (120 wicker baskets which could be automatically unloaded), and the first to create a system that was in constant motion (driven by a team of horses).

The Industrial Revolution saw the widespread proliferation of the railway, with automobiles following not far behind, but the period following the Second World War was something of a second renaissance for cable car technology. Shortages of fuel, rubber, steel, and concrete made road and rail transport tricky, particularly in Europe, but cableways required very little in the way of construction materials and were seen as cheap, efficient, and reliable.

The most impressive relic of this time can still be found in the dense pine forests of northern Sweden. In 1942, a group of 1,500 men were hired to clear a path for a ropeway that would take ore from a mine in Kristineberg to Boliden, where it could be processed. Designs were based on a 26-mile [42-kilometer] cableway that had been built a year previously in the center of the country, but this time the material would be traveling much farther–an enormous 60 miles [96 kilometers]. That makes it the longest ever built, even today.

Construction was rapid, and the first ore gondola was sent down the cable on April 14, 1943–more than four months ahead of schedule. The system, named the Norsjö Ropeway, ran for 43 years before it was shut down in 1986, when heavy trucks finally became a more economical way to transport the ore. Today, only an eight-mile [13-kilometer] stretch survives, converted to passenger transport as a tourist attraction.

It wasn’t only Europe where cargo ropeways proved popular. In 1954, a French-American company began mining manganese in Gabon, but the nearest reliable transport route–the Congo-Ocean Railway–was more than 155 miles [250 kilometers] away, across rough terrain.

George Perrineau, an engineer, was tasked with constructing a transport link between the two and he chose to construct a cableway system–the COMILOG Cableway. The route ran from the mine in Moanda to a town called Mbinda, where a new branch of the railway was built to link up to the existing tracks and take the metal to ports in the Republic of Congo. Comprised of 10 sections, the cableway was equipped with 2,200-pound [one-tonne] buckets that could carry manganese 24 hours a day. It operated until 1986 when the government of Gabon, looking to ship the metal through its own ports, routed a new railway to the mine.

The ability of cable car systems to easily link up with existing transport infrastructure, as seen in the COMILOG cableway example, is a key reason for their third modern renaissance–this time as mass transit.

“Imagine a theoretical city where your home is one mile away from the nearest metro stop,” says Dale. “Servicing that last mile is incredibly inefficient. We have [public transport] funding problems because we have to get people to the subways, to the metros, through that last-mile problem. That’s where our inefficiencies mostly build up–because we use inefficient technologies like buses and streetcars.”

But cable cars, Dale says, are ideal for fixing that problem–particularly when you factor in topography. “They can provide very high-frequency service–less than a minute wait times–at a very comparable cost to buses and streetcars. In a first-last-mile problem, they’re beautiful–basically acting as feeding systems.”

He adds: “With a cable car there is virtually no incremental cost in adding capacity and lowering wait times. With a streetcar or bus system, the incremental cost is significant–in order to expand capacity or lower wait times, you need to buy/run more buses/streetcars and then staff them as well.”

In Medellín, this factor made a real difference to the success of the scheme–the cable car system there is fully integrated into the metro network, so riders can use one ticket for both. “Everything is in one zone,” says Correa, “meaning that someone who lives in the poorest barrios can reach the industrial areas paying less than a dollar. The metro started closing the chasm in those economic terms. The price drops because now they don’t have to take two buses.”

That success has been noted worldwide. Countries around the globe are now rushing to construct cable car systems in much the same way that they were rushing to construct monorails a few decades ago. The success of the Medellín project inspired its local neighbor, Caracas, to construct its own mass transit cable car, as well as other projects in Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Peru, and Colombia’s capital, Bogotá.

In Iran, the Tochal Telecabin system carries winter sports enthusiasts from the city of Tehran to the enormous Tochal ski complex. In Armenia, the Wings of Tatev cable car ferries religious tourists to the Tatev monastery year-round. Mexico City has a proposal for a cable car, as does Haiti, Vietnam, Lagos, Mombasa, and many other places. The list of current proposals that The Gondola Project tracks is enormous.

“There are a lot of proposals out there,” says Dale. “The majority probably won’t get beyond the proposal stage. That doesn’t negate the validity of the technology.”

Even when they’re built, not all modern cable car projects succeed. In London, in July 2010, the city’s transport authority announced plans for the U.K.’s first urban cable car. Called the Emirates Air Line, the proposal was for a privately funded cable car for pedestrians and cyclists between the Greenwich Peninsula and the Royal Docks.

Planning permission was granted, and construction began, but the cost of the project–originally pegged at £25 million [$31.25 million]–swiftly rose to more than £60 million [$75 million], making it the most expensive cable system ever built. “As someone who happens to know a little bit about cable transit systems, let be me completely blunt,” wrote Dale at the time. “There is absolutely, positively, completely no reason whatsoever this project should cost London taxpayers ~$100m USD. Not a single good reason.”

The Emirates Air Line cable car, named after its sponsor, opened on June 28, 2012, a month before the start of the 2012 London Olympic Games. A total of 34 carriages operate at the same time, with a maximum capacity of 10 passengers each. Crucially, the system–despite appearing on the Tube map–is not integrated with the rest of London’s transport network. Passengers must purchase an extra ticket, costing £3.50, to use it.

While the cable car proved immediately popular among tourists visiting the city for the Olympics, its usage fell swiftly once the Games were over. In November 2012, passenger numbers dropped to less than 10 percent of capacity. For every 10,000 rides, only one was made by a regular commuter. Today, those statistics have been lifted slightly by special, tourist-focused night flights (which serve alcohol) but aren’t much better. The project began to attract major criticism, mostly over its taxpayer funding and location.

In 2015, Transport for London commissioner Mike Brown said that he expected demand for the cable car to grow as the areas that it serves are developed (some dispute this). He also noted that the service has built up a £1-million [$1.25-million] operating surplus. But the reputation of the cable car among Londoners is very poor (attracting the derogatory nickname “dangleway“), and that’s unlikely to change any time soon.

Dale picks out the fare structure and the way the system was sold to Londoners as key reasons why the Emirates Air Line is unpopular, though he insists that it’s not a failure in his eyes. “Your narrative around the system is essential,” he says. “Understanding what you’re trying to do. Are you selling this for tourists? Are you selling this for locals? Is it a hybrid approach where there’s a combination of the two?”

He adds: “Tied to that narrative is your fare structure, because your fare structure is what’s going to determine how this thing makes money or not. So you’ve got to make sure to figure out how to get that right, and that ties into your narrative. They’re two completely different demographics. And if you don’t price those markets differently, you’re leaving money on the table and you’re alienating your locals.”

On The Gondola Project’s blog in January of 2016, Nick Chu wrote: “If anything, the Emirates Air Line is a fascinating case study that offers many important lessons on how cities should, and should not implement urban cable cars and public infrastructure. Aspiring gondola-cities would be wise to pay attention to and learn from its successes and failures.”

The rest of Europe is no doubt cautiously eyeing London’s experience with the Emirates Air Line. In 2021, Paris hopes to become one of the first European cities to implement a modern cable car system aimed at commuters. It’s not trying to be a tourist attraction, nor does it replicate existing transit links. Instead, it hooks up the endpoint of one metro line with more distant suburbs separated by a highway and a steep ridge–exactly the kind of problem that cable cars are great at. It’s being considered in the context of a wider, long-term effort to fix transport issues in Paris’s suburbs.

But Paris isn’t alone–the city of Gothenburg in southern Sweden also has grand plans to build a commuter cable car across the Göta älv River to mark the city’s 400th anniversary. The person in charge of the project is Per Bergström Jonsson, and when I meet him in the city traffic authority’s offices on a cold January morning, he’s surprisingly candid. “When I first got it on my table, I thought, “‘What kind of crazy idea is this?'” he says.

It’s not the city’s first cable car. In 1923, a line was built between the Götaplatsen square and the Liseberg theme park to mark the 300th anniversary of the founding of the city. A century later, the technology is back. “We got the idea from the Gothenburgers,” Jonsson says. “But we have started to realize that cable car technology has big advantages if you compare them to tram lines, or bus lines, or other public transport technologies.”

The city’s new cable car will run from Järntorget square, over the river to the Lindholmen campus and science park, then up to Wieselgrensplatsen where it meets one of the tram lines that radiate out from the center of the city. The aim is to create a shortcut that people can use to transfer between those tram lines without having to go all the way into the center.

“Two and a half million [people] is at least what we are quite certain will use the cable car as a shortcut in the public transit system,” says Jonsson. “They are already using the transit system, and they will gain from using this as a shortcut. On top of that, we will have tourists, we will have new travelers, and we will have travelers that are pedestrians or cyclists that will change to using the public transport system because of the cable car.”

One interesting unknown is what percentage of users will be scared of heights. “It should be somewhere between eight percent and 12 percent, but we really don’t know,” Jonsson says, admitting a little sheepishly that he’s a member of that group.

“But you must have been on a lot of cable cars,” I say.

“I’ve been in some, and some of them are quite scary,” he replies.

In Sweden, building a new public transport system is a cooperation between the municipality, the region, and often the state, too. The country’s consensus-based decisionmaking culture means that things tend to take a little longer than they might in other countries, so final approval–the “point of no return,” as Jonsson calls it–will arrive in mid-2018. “After that we will start building,” he says.

While the politicians deliberate, his office is in the process of securing the various building permits for the construction–no simple task. The bottom of the cable cars will need to be at least 148 feet [45 meters] above the surface of the river, so that boats can pass underneath. On land, they must pass 98 feet [30 meters] above buildings. “That’s a fire restriction, actually,” says Jonsson. “If you have a fire in the building, so that the cables won’t melt from the fire.”

So far, the public favors the idea. “About 75 percent of Gothenburgers like the idea of traveling with cable cars. Almost 70 percent even like the idea of having the cable car outside their house. That’s remarkably high, so far,” Jonsson says. “The general way of seeing the cable car project is a little bit too cheerful, I think,” he adds, stoically.

To preempt complaints, his office has been actively asking citizens what worries they might have–so they can be solved in the planning phase, before construction begins. The biggest fears are privacy, Jonsson says, and rider safety. “It’s a driverless system. We will have people on the platforms, in the stations, but not in the gondolas, and the ride is four-minutes long. Things could happen during those four minutes. I think that if we don’t solve that in a way that the Gothenburgers accept, we will not build it.”

Early ideas to address the rider safety issue include a high frequency of gondolas (“If you are uncomfortable with the persons that you’re about to board with, you can wait,” says Jonsson), safety cameras, a communication system, a staffed cabin every half-hour, and even the ability to reserve individual gondolas at low-traffic times.

Jonsson is also keen to emphasize that the Gothenburg system will be integrated into the city’s tram network–unlike the Emirates Air Line in London, which he describes as “badly planned.” Ridership will be heavily weighted toward locals, who’ll outnumber the tourists at least 10 to one, but Jonsson says that the final numbers will be heavily dependent on how close they can get the cable car terminals to the tram stops. “If we get one and a half minute’s walk, it will be 5,000 [people per day],” he says. “If we have 30 seconds’ walk, it will be 13,000.”

Most impressive of all, though, is the technology that will go into the cable car system itself. The Gothenburg scheme will run on three cables–two for support and one for pulling. That allows for up to almost a half-mile [one kilometer] between towers and exceptional wind stability. Traffic on the city’s bridges is limited at wind speeds of 49 m.p.h. [22 meters per second], but Gothenburg’s cable car should be able to operate safely at speeds of up to 60 m.p.h. [27 meters per second].

“The London system, which is a monocable, shuts down at 14 metres per second [31 m.p.h.]. It’s down about 30 days a year due to wind, and that’s not acceptable for us,” Jonsson says. I ask how many would be acceptable. “One,” he says. “Perhaps a half, one every second year. The cable car won’t be the first system to be shut down when we have bad weather, it will be the buses and the ferries.”

The scheme is due to open on June 4, 2021, and if it’s a success then more lines will follow–along a similar principle of creating shortcuts in the existing transit network. “We will have the first one up and running for one and a half, two years, to see if it’s a good idea,” says Jonsson. “If it turns out to be a popular way of transporting yourself, we will start building the next one four years after that.”

While reporting this story, there was one city that kept popping up–La Paz. The Bolivian capital has the most extensive network of cable cars in the world, named Mi Teleférico, stretching nearly seven miles [11 kilometers] across the city, with another 18.6 miles [30 kilometers] under construction. Cars depart every 12 seconds, seating 10 passengers each, yielding a maximum capacity of 6,000 passengers per hour–a true “subway in the sky.”

“It’s building the backbone of the city’s transit network on cables, and that’s never been done before,” says Dale. “When I said before that they’re really ideally suited to first-mile problems, feeding into a higher-capacity system, La Paz is really challenging that idea, and saying–”‘Hold on a second, why don’t we use this as our trunk, as our main form of public transit’–which is totally unique.”

Ekkehard Assman is the head of marketing for Dopplmayr, an Austrian firm that specializes in the manufacture of cable cars. To date, the company has built more than 14,700 installations in 90 different countries–including the system in La Paz. “It’s more or less the first real cable car network in a city,” he says. “Three lines are already working and have already transported more than 60″”70 million people since they began running in 2014. In addition, we’re on the way to building six more lines and I heard a couple of days ago–they’re not signed yet, these contracts–but President Morales has already talked about two more lines.”

Mi Teleférico combines best practices from all around the world. Prices are rock bottom–about 35 cents for a ticket–while usage is almost all local. “There’s not a lot of tourist things going on there,” says Assman. “It’s more or less pure urban transport.”

While the system opened in 2014 amid the growing global craze for cable cars, the city’s precarious topography means that the idea has a much longer history than other projects. In the 1970s, a team working under councilman Mario Mercado Vaca Guzmán planned a route between the neighborhoods of La Ceja and La Florida. In 1990, a feasibility study for a similar route was performed, but ultimately rejected over high fares and low passenger capacities. In 1993, mayoral candidate Mónica Medina included aerial transit as a campaign promise, pledging a system of interconnected cable car lines.

The idea kicked around for another two decades until July 2012, when Bolivian President Evo Morales called together the mayors of La Paz and El Alto and the governor of the La Paz department and finally got them to make it happen. Funds were provided by the country’s national treasury and the Central Bank of Bolivia, and the doors of the cabins opened for business on May 30, 2014.

Like in Medellín, there have been enormous positive effects on social mobility–the cable car runs between La Paz and the neighboring El Alto, a poorer area with a majority indigenous population. Travel between the two areas has historically been difficult, due to a 1,300-foot [400-meter] altitude difference, but the cable car system has broken down the physical barriers between the two dramatically different populations–and perhaps a few of the psychological ones, too.

As a technology, cable cars have a lot of factors in their favor. They bridge tricky terrain. They efficiently get people to and from bigger mass transit systems. They’re cheap to build and maintain, and the newest designs are safe in even extreme weather conditions. They’re modular, quiet, clean, and run on electricity rather than polluting fuel.

It’s also clear that the technology has to power to effect major, positive change in the world’s cities. It’s not as simple as slapping down a cable car and inequality disappears. “Something that we, in Latin America, have learned is that you cannot copy and paste models and expect them to work perfectly,” says Correa. But if integrated well into existing transit networks, sold properly to the locals, and suitably priced, they can deliver tremendous benefits–both to underserved communities and cities as a whole.

But perhaps the most interesting aspect of the technology is the reaction that it generates in people. When confronted with the idea of cable cars as mass transit for the first time, some people respond with horror or fear, others with mirth or excitement. “I think it’s just”¦ what’s the phrase? Lightning in a bottle, a perfect storm, something like that,” says Dale.

In his job as a cable car consultant, he speaks a lot to city planners who’ve been told to go away and research the subject. “I’ll be honest–the first thing that half of our clients say to us when we pick up the phone is: “‘Is this the stupidest idea I’ve ever had?’ You can hear it in their voice, you can hear fear,” he explains. “Because they know if they get it wrong, they’re going to be jumped on at work, they’re going to be humiliated, people are going to laugh at them and all of this.”

The best part of the job, Dale says, is watching people come around to the idea. “I get a thrill, quite honestly, from being able to take people from a place of thinking, “‘This is the most ridiculous idea in the world’ to a place where they go, “‘This actually isn’t ridiculous at all.’

“So many of the decisions that get made in the urban planning sphere are emotional decisions, and to see [planners] actively confronting that fear, that is unbelievably rewarding and unbelievably exciting.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Going Places section, which looks at the impact of transportation technology on the modern world. Click the logo to read more.