In some ways the first Martian colonists will have it easier than the colonists of Earth’s history. Rather than a rag-tag group of religious outcasts, or refugees from war and famine, the first Mars residents will have undergone years of physical and psychological tests to determine the optimum group for the mission.

But that doesn’t mean it’ll be a walk in the park. The first colonists will face an intimidating task in establishing humankind’s first outpost on another planet. After a long voyage, they’ll have to deal with a hostile environment, limited supplies, and the pressure of knowing that everyone back home is counting on them.

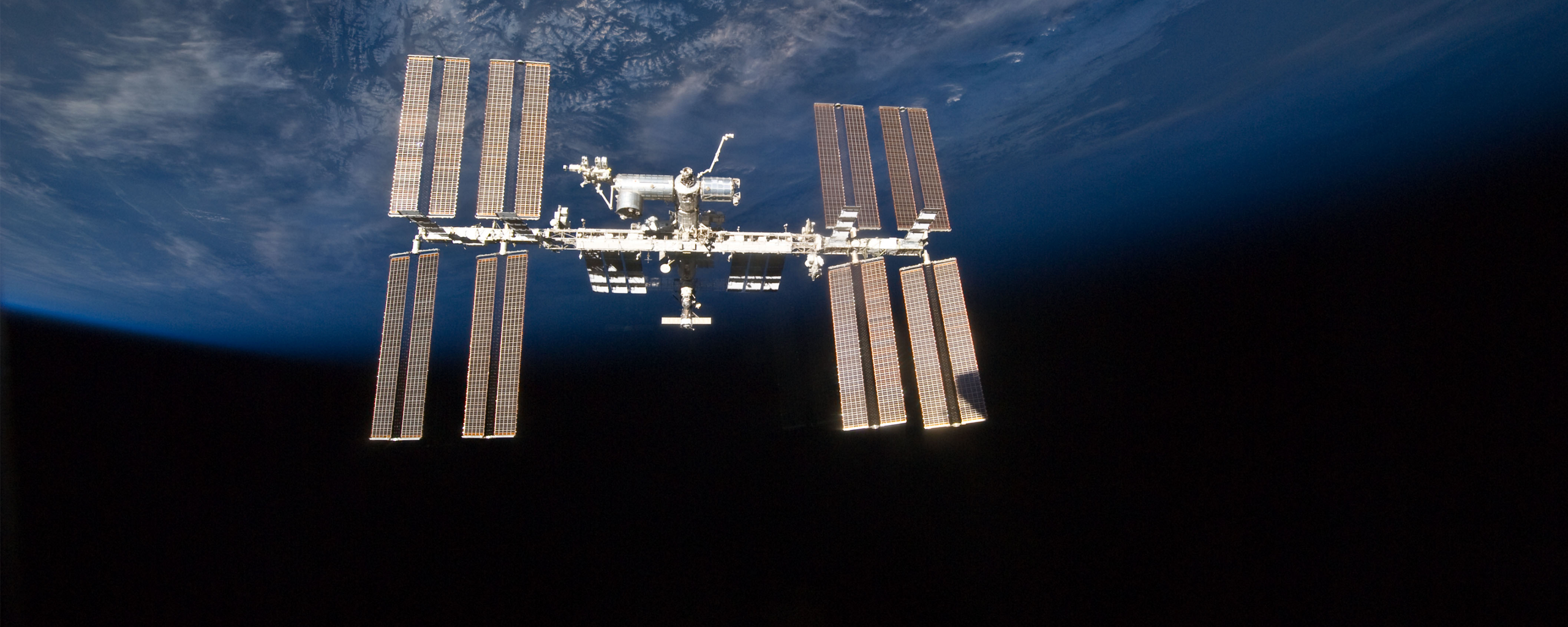

Figuring out who’ll best be able to cope with the myriad challenges involved–both foreseen and unforeseen–is no easy task. To survive, these first colonists on Mars will have to get used to living in a confined environment with people of different backgrounds and ethnicities, much like the multicultural group orbiting the Earth on the International Space Station now. As such, a lot of the same selection principles that go into choosing astronauts today will apply.

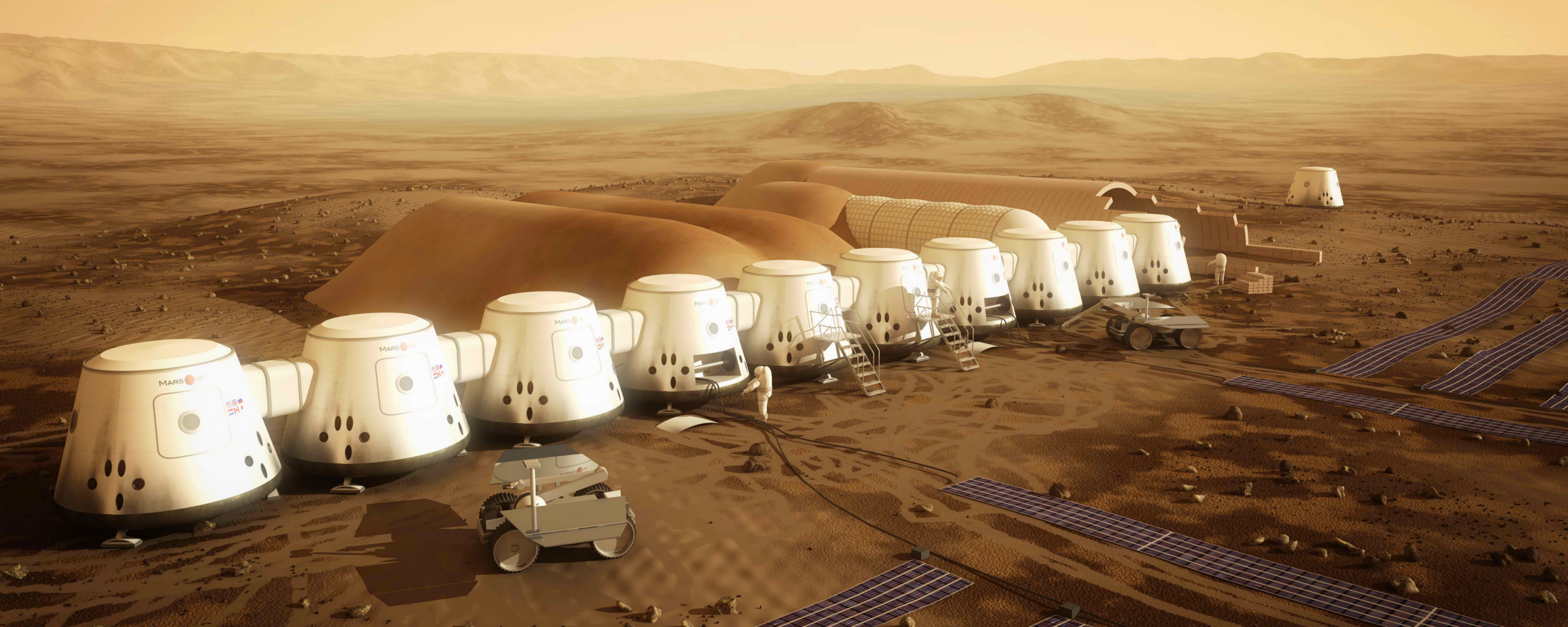

“They live in a tin can and there’s no “¦ escape,” said Norbert Kraft, the chief medical officer running the worldwide astronaut selection program for Mars One, a somewhat controversial endeavor hoping to send colonists to Mars in the 2020s. Despite widespread criticism that Mars One’s model looks more like a reality show than a scientific endeavor, the organization is currently the only group actively recruiting Martian colonist candidates.

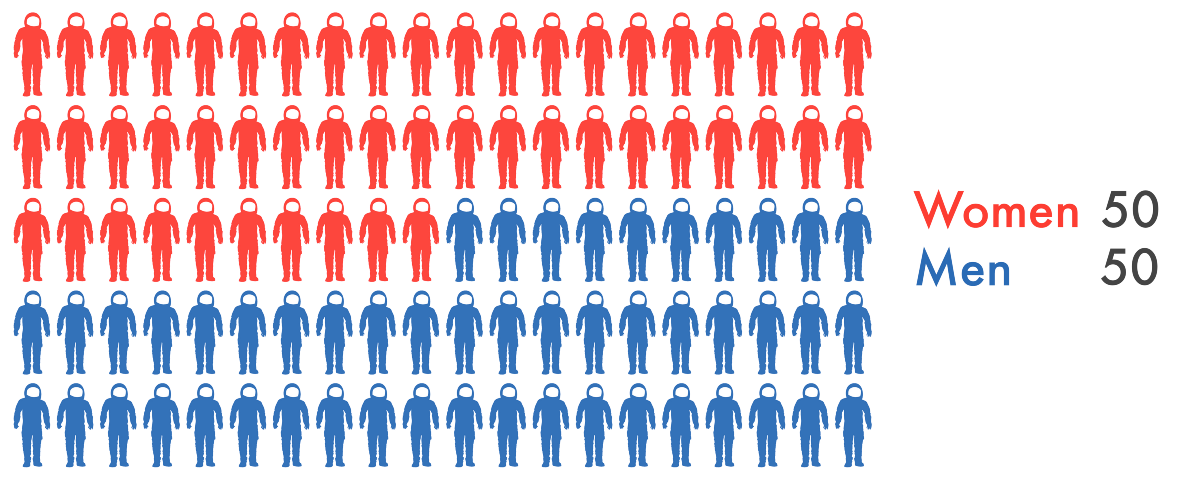

When making his selections, Kraft looks for people who display a degree of emotional intelligence, letting him know they’ll be able to make interpersonal and cross-cultural connections. “We like to have diversity because it brings so much more creativity,” he said, of both the multicultural and gender variety. “The opposite side of the coin is that everybody has different approaches, different thoughts, different behaviors, and you really have to understand how to deal with it.”

Complete isolation for crew members will be new for a Mars mission, however. Astronauts on the ISS can escape one another, in a way; they can video chat with their families back home. But when colonists go to Mars, communication times will be longer. Care packages aren’t feasible. They will need to create their own family unit.

To address this, Mars One plans to train its travelers together for 10 years before they even get on the rocket. That will make the crews of four feel more like family than co-workers. In fact, Kraft turns to a classic example of a well-functioning crew for his ideal model.

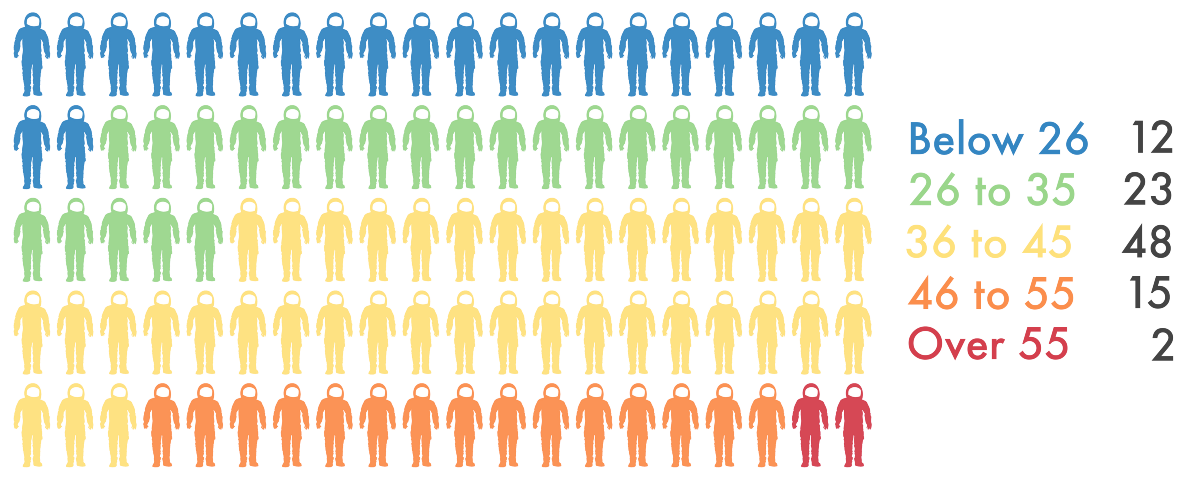

“You have Star Trek: The Next Generation. You see the captain, the older one. You see the young boy. You see different cultures. But they have a kind of family structure,” he said. “The older person has more experience and [a calming presence] “¦ and the younger person [is] pushing forward. That is an ideal combination for especially the first group.”

The family mentality may become literal one day. Kraft hopes that some groups will eventually start families on Mars, making the colony truly sustainable.

While this kind of independent, self-sustaining colony is certainly a future goal, there are many questions around how we can achieve it–not least of which is how many people will be necessary to get such a colony up and running.

“What is the minimum number when you can actually consider it a colony and not just a settlement?” asked Chris Carberry, who thinks a lot about the future of Mars travel as the CEO of the nonprofit group Explore Mars. “Is it over 100? Is it over 50? Is it over 1,000? Obviously you want sustainability and you want “¦ to make sure you have enough variation in your gene pool if you want to actually go forth and multiply, to create an actual growing, thriving colony.”

Sometimes he speculates about the possibility that, down the line and once the basic ability to survive on Mars is established, some religious or political groups might send a cluster of people to set up their own little utopia, just like the Pilgrims of the 17th century.

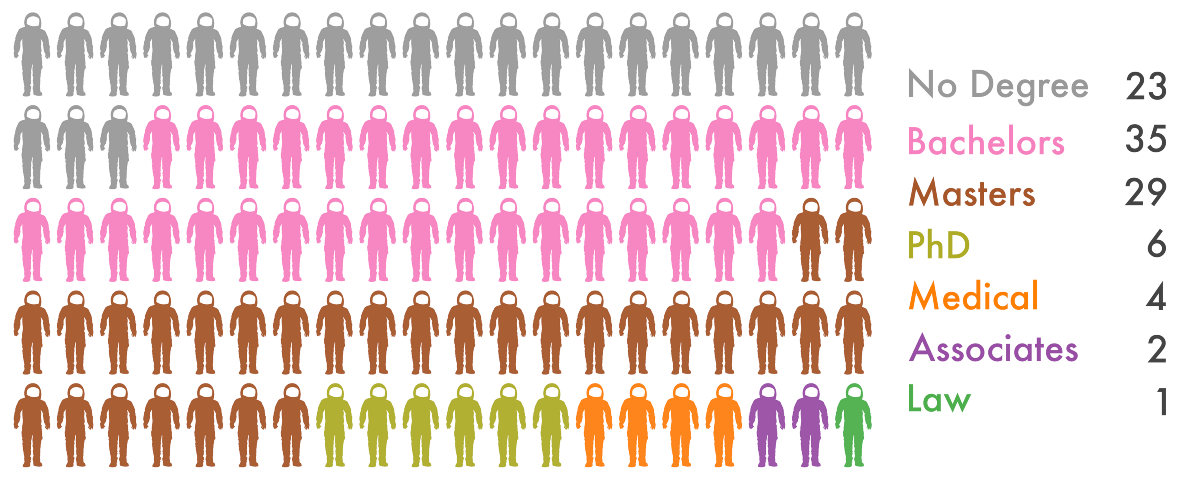

But especially at the outset, the selection process will be much more pragmatic. One of the keys to a colony’s success will be to make sure everyone knows how to do each job. To that end, Mars One training will focus on learning skills. Some of the applicants are doctors and scientists. But one is a beekeeper. Another is a dishwasher. Many of the applicants don’t have college degrees. But they have all proved they can learn.

“They have to be specialists in all the areas,” said Kraft. “It doesn’t help me if one’s a medical doctor and someday gets sick and nobody can help anybody anymore.” That’s one of the reasons a return trip isn’t part of the ticket. They’ll train together for 10 years. But if, once they get on Mars, one person wants to come home, that entire team unit will fall apart–compromising the entire colony.

The idea that everyone should know how to do everything reflects the current expectations for astronauts staying aboard the ISS. There are specialists, of course, but everyone needs to know how to run all of the different modules. “Only one astronaut cannot operate the system,” said Koji Yanagawa, a member of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency who has spent 10 years working on astronaut selection. “A group of astronauts have to participate.”

While astronauts are currently chosen for their abilities to manage these huge systems, Yanagawa believes the first group to live on Mars should probably be more science-minded. “When you go to Mars with a group of 100 to 200, the scientists should be a major prioritizing factor,” he said. Being able to think critically and scientifically will help the colonists work through any unexpected hurdles Mars will throw at them.

James Picano, a senior operational psychologist at NASA, feels certain that whatever happens with a Mars colony, it will be built on the lessons space agencies have learned throughout the decades. The ability to handle stress, be a good roommate, work as a team, and learn many different skills–these have been and will continue to be true of space travelers from Apollo to the International Space Station and beyond.

“That sort of exploration spirit, that expeditionary spirit, will set those folks apart from many,” he said.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Above & Beyond section, which looks at our understanding of the universe beyond Earth. Click the logo to read more.