By the time I leave America, my palate is always exhausted. Eating in the country, even for a week’s time, brings me right back to my childhood: I re-acquaint with the exact texture of a bit of blackened bacon, pooling in its own dark fat; or the unique mouth-feel of fountain soda in a cup, tinged with the flavors of plastic, wax, and the faint metal of local water. I can summon the slick that the middle of an Oreo leaves behind on my tongue. I have an entire library of articulate memories like these. But somehow, at the same time, I can’t taste anything. When a waiter in a restaurant asks me, “What’s lookin’ good to ya?” I flip through five-page menus and realize I don’t really know.

Growing up in Massachusetts, I lived through an era of progressive and escalating official dietary prescriptions, to which my diet-conscious mother successively subscribed. She loved to have rules about what foods could and could not enter our home. It seemed like everyone–her, the media, the supermarket shelves exclaiming like the vivid, breathless panels of an action comic–raised me with the notion that appetite was some kind of moral quality, and it was the latest diet fad that told us how to be good.

I live in London now. But years later, whenever I visit home I can’t get my head around what good means anymore when it comes to food.

I was four years old when I saw the 1985 Live Aid concert on TV, with everyone fighting hunger. Hunger, then, was for far away, unknown, and uncivilized places; surely where I lived no one ought to be hungry.

After all, hunger was negotiable. You could overcome it by privilege and will, wrestle it like a bull. You could deny it with swollen, radiant-orange Metamucil fiber shakes, or soothe it with candy bars. In the commercials of my childhood, productive corporate workers gleefully managed the inconvenient sensation when it arose with Mentos or Snickers stashed in their desks. In the United States, there weren’t famines. Food was a product of abundance, a very marketable commodity.

The American Heart Association says 78 million adults and 13 million kids (or 28.5 percent of the country’s population) are obese as of 2016, an epidemic that spells some $190 billion per year in weight-related medical bills. While generations of diet trends and health fads have come and gone, adult obesity in the United States has more than doubled since the 1960s. That’s not actually out of line with global trends: Worldwide, it has also doubled since the 1980s, with 13 percent of the world’s adult population categorized as obese in 2014.

Despite the fact we’ve come to associate thinness and dieting with good health, plenty of studies–like this recent one out of Europe–show that overweight people have no greater risk of dying from heart disease or cancer than others, and that metabolic fitness has nothing to do with size.

It’s other diseases like diabetes, insulin resistance, and high blood pressure that endanger people with high weight–illnesses caused by stress, lifestyle, and the consumption of sugar. And among diabetes and heart disease sufferers, some studies say the thin ones actually die younger than the obese. The Journal of the American Medical Association even found that overweight individuals live longer in general, a revelation the medical community seems reluctant to accept.

But dietary guidelines and food marketing alike have aggressively conflated weight loss with health for decades, creating a $2-billion industry of fads, exclusions, and inventions that have overwhelmed us–even undermined us. The AHA reports that obese people now have less ability to “resist food cues” like hunger and fullness, thanks to disruptions in their body’s internal logic. It might even be the food and diet industry that’s causing it.

Picture me at six years old with a playmate, standing side by side on kids’ step stools, pouring chocolate milk slowly into a bowl as if filming a commercial. “Mmm,” we purred dutifully. “Taste the indulgence.” Abstractly I already understood the word indulgence before I could spell it, because of food ads. Indulgent was chocolate SlimFast, which tumbled through afternoon television in soft brown slow-motion. At the end of the ad the can would be wrapped in a belt or measuring tape, cinching its skinny waist. By the time I was 16, I was asking my mother to buy me cases of SlimFast from the pharmacy. I remember the taste, but not what, if any, “sensible dinners” I had alongside the plan. My appetite had become dislocated, like a joint.

When I think about being a small child at the beginning of the 1980s, I think about the word diet. It was a noun (you could be on one), a verb (you were dieting), or an adjective (Is this diet? I’d ask about a beverage or Jell-O). Our house filled up with diet soda–as if to signal that having a drink with no sugar in it meant something was happening, like it had an agenda somehow more directed than plain water. Why do you only have diet? my school friends would scornfully demand, and I didn’t really know. What I did know was that springy aerobics ladies drank Crystal Light, and that had to mean it was a health drink, a beauty tonic. I was too little to know that tastier beverages had calories and Crystal Light didn’t; that’s why it was supposed to be good for you. I didn’t even know what calories were. I only remember feeling certain that as long as we only had diet drinks in the house, we were going to be healthy.

Indeed just a few years before, a triumphant, startlingly thin Oprah had dragged a red wagon full of 67 pounds of fat onto her television stage to represent the amount of weight she had lost with an extreme diet called Optifast. While on it she had 400 calories a day, entirely in liquid nutrition shakes (an average woman trying to lose weight is said to need 1,500 calories a day).

As calorie-obsessed as the country was back then, as of 2011 one data set found that the average American’s daily calorie-intake was as high as a whopping 3,641–which was a few hundred calories higher than averages in Brazil, Russia, South Korea, Kuwait, the United Kingdom, and Germany, but unsurprisingly well outdoes those in Vietnam, Japan, and Somalia.

Today we aren’t so sure about artificially sweetened, low- or no-calorie “diet” drinks. Although the FDA says diet soda is harmless, lots of dietitians believe the additives in it are bad for your teeth and bones, and mostly unsubstantiated rumors of aspartame’s relationship to cancer persist. Self-titled “anti-sugar guru” Brooke Alpert says the fake flavor “confuses” your palate, leading to more sweet cravings and the release of insulin–which could explain the higher risk of Type-2 diabetes and higher weight often associated with drinking lots of diet soda.

One study even found that those who drink diet soda regularly gain three times as much belly fat as those who don’t. Although consuming sugary drinks causes weight gain and eventual insulin resistance, too, there’s enough evidence to suggest that the fetish for “diet” actually made people more obese, less able to read their body’s cues. The Crystal Light ladies might have saved us calories and sugar, but at the long-term cost of our sugar metabolism and unmooring us from our sense of sweetness.

No sooner had the 1980s kicked off properly than my mother and I found out fat was bad. Remember the utilitarian Food Guide Pyramid? It hung on the wall in my elementary school, with a tiny golden triangle of fats and oils on top like a crown. Now we knew that fat made you fat. It seemed nothing else in life mattered as long as you got rid of it.

By the early 1990s, our house was filled with fat-free yogurt, fat-free pudding, and fat-free ranch dressing. Every grocery aisle and pantry was lined with the distinctive green livery of Nabisco’s Snackwell’s cookie brand, which promised fat-free Devil’s Food cookies and fat-free vanilla creams. In ads, fanatical women swarmed a Snackwell’s employee who could not keep up with demand. It was a marvelous trick wrought by what felt like cutting-edge science: a delicious dessert, but one assumed to be utterly free of consequences. If you were fat-free, then you could be guilt-free.

Guilt-free, the drumbeat of the 1990s. Any undesirable ingredient was cause for guilt. There were even guilt-free, fat-free Lay’s potato chips, a virtual impossibility since even I knew that the food pyramid’s golden fats and oils were a key component of potato chips’ very making. The secret was Olestra, a synthetic fat substitute that the body can’t absorb. My guts were always in knots from this sort of thing, after the entire boxes of Snackwell’s and the bitter, cardboard-textured bags of fat-free Lay’s I regularly inhaled after school. I was simultaneously always hungry and somehow gaining weight.

Amid all this guiltless fanaticism, much to our national chagrin we learned that Olestra could stutter suddenly out of our bodies at unwanted times, spotting undergarments. The appetite for it was short-lived; it’s now more likely to be used as an ingredient in paints and lubricants.

The low-fat craze only made Americans fatter, as well as less healthy. Experts now say this fixation on fat misled people into forgetting about other means of gaining weight–like simply consuming too much food or not getting enough physical activity. It turns out those irresistible Snackwell’s tasted just as good as full-fat cookies because they were loaded with sugar. And the “use sparingly” advice on fats led by the Food Guide Pyramid (itself now often criticized) failed to teach consumers how to differentiate between “good” and “bad” fats. We now believe that plant oils such as olive oil are necessary for heart benefits, and that the right fats help you absorb vitamins and actually experience satiety.

It was near the end of the 1990s, by which time Oprah had gained back all her weight, that dietitians told us what we had really forgotten about were carbohydrates. Ah, yes. It was the carbohydrate that was bad and wrong. While the Atkins diet, which advocates counting carbs rather than fat and calories in favor of higher-protein, higher-fat meals, was actually first introduced in the 1970s, it never reached “craze” status until the beginning of the millennium. By then, some 30 million Americans, including my parents, were on Atkins. According to reports, sales of carbohydrate-rich foods like rice and pasta fell 10 percent at the Atkins peak between 2003 and 2004.

Suddenly, if you wanted to have a McDonald’s bacon double cheeseburger, you could so long as you took the bun off. I can remember being relieved that I could stop counting calories, and unburdened that I could stop feeling so guilty about eating cheese. Mainly, the problem now was bread: My parents started anxiously asking restaurant servers to take the baskets away, not to bring them in the first place. And the truly health-conscious like me worked dutifully to veto all grains from our lives forever, but it was difficult. Bread was seductive and decadent. Bread could even be addictive, according to Dr. Robert Atkins, who said we needed to treat it like it was a drug.

The goal with Atkins and other popular low-carb diets was to reach a state of ketosis, which means deriving energy from ketone bodies in the blood made by the liver from fatty acids. We love the idea of excreting fat. You could tell if you were in ketosis or not by using urine test strips, or by waiting for an acetone taste and the smell on your breath. That’s right: If you had a gross taste in your mouth, you thought you might smell bad, and your pee sticks turned the right color, that meant your diet was working and that health was just around the corner.

By 2005, though, Atkins Nutritional filed for bankruptcy. The diet required punishingly strict adherence to be effective, and consumers were being bombarded with expensive and overwhelming low-carb products (over 3,000 new low-carb nutrition products were released during the Atkins diet’s relatively brief lifespan). Although studies suggest low-carb, ketogenic diets are more effective than low-fat diets for weight loss and that they also lower dangerous blood cholesterols, the saturated fat in meat-heavy diets ultimately increases the risk of heart disease. Ketosis is unpleasant and difficult to maintain, slows down the overall metabolism, and may even make the body more sensitive to sugar, all of which means that the weight returns with a vengeance if the dieter “slips” or attempts to return to a more balanced plan.

Ten years later, a surging and joyful Oprah exults about bread. Marketing Weight Watchers, she calls it the joy. “I don’t deny myself bread. I have bread every day,” she boasts defiantly.

In the back half of the 2000s, I loyally tried juice cleanses and juice detoxes (turns out your organs are supposedly quite well-equipped to detox themselves and kale smoothies have no bearing on that fact). I tried a raw food diet, which mangled my digestion, and briefly attempted to eliminate gluten, to no real effect. It is very easy to believe that we now face a battalion of previously unknown or uncommon food allergies and intolerances, our guts tenderized by these years of mixed messages. Or maybe it’s the hormones in meats, or Monsanto and the GMOs, which are the next frontier of argument.

Today we favor nutritious “superfoods,” so-called clean eating. Obsession with one’s nutrition, even over the concept of dieting, has even evolved into a new eating disorder called orthorexia nervosa–unlike anorexics, who avoid food in a compulsion to lose weight, orthorexics avoid any food that seems unhealthy or impure, compelled by some impossible and restrictive idea of health.

We’ve started to ask questions about whether we should eliminate genetically-modified foods–even though fortified foods and an ongoing relationship between science and agriculture has the potential to fight malnutrition, hunger, and other global health problems. Empirically, it seems harder than ever to know what we are supposed to eat.

When it comes to food, the United States is unusual. The protein-centric, veggie-ridden dinner plate–which it now effectively markets to the rest of the world–is actually a “culinary anomaly,” according to chef and food scientist Dan Barber. Americans get 37 percent of their total calories from fat and sugar (the world average is 20 percent), while eating more calories overall per day than any other nation. Current restaurant culture, with portions now four times larger than in the 1950s, is thought to be one of the biggest threats to our concept of healthy eating.

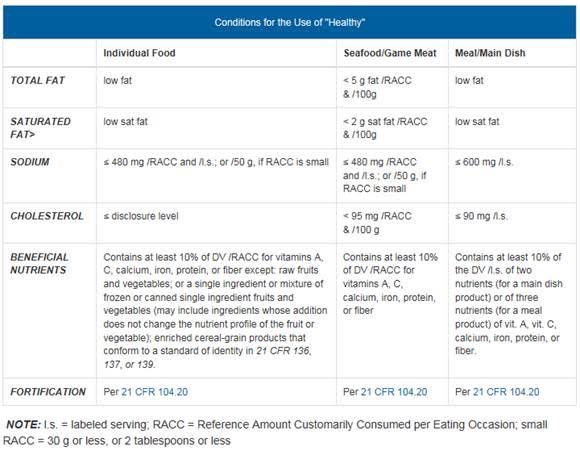

So, what’s “healthy?” In early May, the FDA began freshly considering the word–or, specifically, what is required to put it on a food label. “Healthy” and its related incarnations (“healthier,” “healthily,” “healthiest,” etc.) can be used as an “implied nutrient content claim” if it meets the conditions in the following table, as required by this document–21 CFR 101.65(d)(2)–which is not an easy read.

The only thing we seem to be pretty sure about these days–the one constant across years of conflicting recommendations and diet fads–is that sugar is very bad. While a British scientist argued in the 1970s that consuming sugar was a greater danger to human health than fat, no one listened to him. Now we know it’s the presence of Type 2 diabetes, caused by too much sugar, that can make carrying too much weight so risky.

To address this, Michelle Obama has promised changes to nutrition labels that suggest a clear limit on daily sugar, of course amid great pushback by Big Sugar. The Sugar Association (there’s a Sugar Association?!) is stridently against this modification; the industry’s Bruce Silverglade said “the demonizing of a specific ingredient like fat or cholesterol has not worked in the past,” and suggested the new labeling might even invite litigation.

It’s still so easy to be exhausted by the conflicting ingredient hierarchies and the constant onslaught of flavors both organic and invented. Dietitians and food scientists agree that the American way needs to change–less processed gratification, more locally grown agriculture. Marion Nestle, New York University professor of nutrition, food studies, and public health, told TIME that “serious advocacy and political engagement” is necessary to avoid a “two-class” food system in the future, where some have access to the fruits of sustainable farming, while others remain stuck in the cycle of cheaply made industrialized food.

She’s probably right: If we’re still facing a $2-billion diet industry that continues to falsely promote weight loss as the path to nutrition and health, and the suggestion of limiting sugar is met with the threat of lawsuits, then the engagement Nestle suggests can’t start happening soon enough.

Back in London, I eat what I like, exercise, and am in good health–as far as I know. I’ve decided, more or less, to lay these last few decades of strange noise and false flavors to rest, not to overthink what I eat.

Just a last week, though, when boarding a plane to New York I did hear three women discussing something called Isagenix. The women looked fit and wonderful, so out of curiosity I visited the Isagenix website, which promises a revolutionary new health and wellness solution by way of cleansing and energy-stimulating nutrition bars and shakes. I should replace some of my meals with Isagenix products, it said, entreating me to lose weight with Isagenix SlimCakes, Pro Shakes, and Whey Thins.

As I scrolled through the site, I was immediately reminded of buying a carton of SlimFast at 16. This is all so awful, I thought–even as I experienced a familiar old flickering of desire to try it. It’s possible very little has changed, and we haven’t learned anything at all. Or maybe it’s just that learning won’t save us.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Vital Signs section, on the future of human health. Click the logo to read more.