I went on my first diet when I was 15. I flipped through fashion magazines, somewhat lazily back then, so I would know what was in vogue: blood-red lipstick, combat boots with a slight heel, whiter teeth, thighs narrower than your knees. I didn’t care much for any of that until someone told me my face looked chubby when I wore pigtails to school. Suddenly, what was being sold to me in those pages seemed relevant. I wanted to look different. I wanted to feel better.

Since that day at 15, those feelings have never left. In some ways, I’ve been on a diet–or miserably failing at one–for 18 years. It wouldn’t be far off to call me an expert. I’m an American woman, after all.

My first diet coach was Suzanne Somers. My mom bought her book, and we started Somersizing. We cut out starches and sugar, and ate specific types of food together (or separately) to promote better digestion and weight loss. My freshman year of college, I counted calories judiciously and ate not much more than a lot of white rice and steamed vegetables in the dining hall. Two years later I joined Weight Watchers and counted points during the summer I interned in New York City, arriving for my weekly weigh-ins sweaty and exhausted after having transferred train lines at rush hour.

I tried the Paleo diet for a week with a guy I once dated, who evangelized at every opportunity about how energized he felt when adhering to the ancient food regimen. In turn, I got so cranky that I dumped him and went on a chocolate-cake binge that lasted days. I’ve used MyFitnessPal and Lose It! to log my meals and count calories. I’ve given up gluten in the hopes of improving my digestion, choked down metabolism-boosting teas I bought on the internet, and even stopped eating altogether for a few days during a Hollywood juice cleanse purchased at the local drugstore.

I’ve lost weight successfully. I’ve gained it back and tried again. I’m in my 30s now and have evolved, for the most part, past that constant worry of being culturally skinny. I just want the clothes in my closet to fit and hate feeling like I can’t move the way I want to when spring comes. I get antsy when I’m carrying unnecessary weight.

That’s why when I heard about Lark, the personal weight loss chatbot that offers “unlimited personal guidance and support, anytime, anywhere,” all from an app inside my phone, I was more than game to give it a go. Apple voted it one of the “Top 10 Apps of 2015” and Vogue described it as a cheerleader that “ultimately feels like a friend.” Another reviewer liked its cheerful approach to relaying her health statistics and looked at it “kind of like my own little life coach.”

So, a chatbot that acts as a virtual, personal trainer and nutritionist coach by automating some of the world’s best health experts? Yes, why wouldn’t that be the next iteration in losing weight and keeping fit?

No diet is fun. Anyone who tells you that is spewing myths. Watching what and how we eat is, however, a good idea for many of us–and actually growing in importance. Recent World Health Organization estimates indicate that worldwide obesity has more than doubled since 1980, leaving us with more than 1.9 billion overweight adults in 2014, 600 million of whom were considered obese. That means 39 percent of the global population has a body mass index placing them squarely in the category of overweight. This uncontrollable weight gain has been called an epidemic; it’s also one that’s considered preventable.

That’s all to say that I’m in favor of any new technologies that encourage mindful eating and better nutrition around the world. Especially when–like Lark–they’re developed by health and behavior researchers at Stanford University and Harvard Medical School.

Even so, I feel a little anxious downloading the app onto my iPhone. While I’m very accustomed to the idea that our bodies are public, canvases we paint up with clothing and parade about in the outside world, the exercise of dieting feels private. What I put in my mouth, in the privacy of my own home, is my choice. I don’t know what to expect with a bot monitoring me, at the ready with immediate feedback about whatever it is I’ve just consumed.

Day 1, Thursday, April 21

Opening the chatbot, I expect that Lark will actually talk to me as Siri does, or at least let me voice-chat with it. Instead, everything is text-based. “Good morning, Abby!” it says, before asking permission to integrate with my Apple Health Data. (Full disclosure: I’ve never opened the preinstalled Health app on my iPhone, but apparently it’s capable of collecting data about everything from my blood alcohol content to my basal body temperature to my cervical mucus quality. Some of that data it extracts from wearables like the Apple Watch, and other information it tracks by integrating with third-party apps of your choosing.) I’m confused by the data category overload when I open the Health app but allow Lark to access everything anyway.

Next, Lark wants to confirm my bedtime and wakeup times. It lists a 9:42 p.m. turndown from the night before and thinks I got up at 5 a.m., when my phone’s alarm went off. It gives me the option to affirm its assessment or otherwise edit it. I tap edit and enter 6:30 a.m. as the actual time I got out of bed after hitting snooze. I suspect it’s guessing my sleep time by the number of hours my phone was dormant, but when it says “8 hours, 48 minutes, that’s more than you usually get on weekdays!” I’m alarmed. How does it know how much I normally snooze?

I find the sleep icon and click on it, realizing that Lark back-populates with information my phone has already stored. It knows how long I’ve slept for the past seven days. The range is anywhere between seven hours and 26 minutes, and nine hours and three minutes.

Next, Lark notes that I’ve only logged 36 seconds of activity this morning, which is apparently “not quite at its usual weekday level. But that’s alright, each day’s a bit different.” At this point, I’ve been awake for maybe 20 minutes and have had only a few sips of my morning coffee. It feels like I’m already being told that I’m lazy.

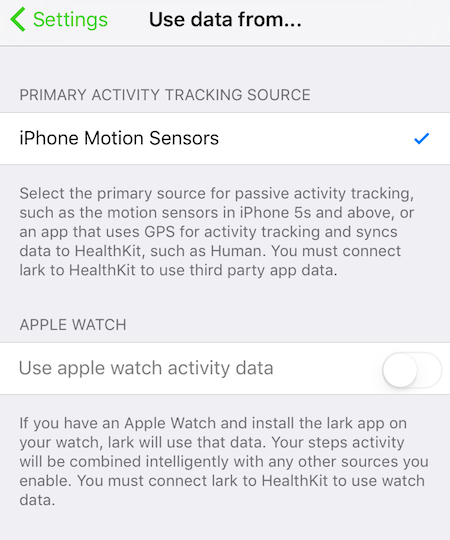

I dig around a bit in the app to find that its primary activity tracking source is my iPhone’s Motion Sensors. It’s using the same thing to track my sleep. It also lists my “normal” activity levels. Those range from nine minutes a day to one hour and 51 minutes over the last nine days.

Under the settings tab, I see that without the Apple Watch on my wrist the app is going to be pretty limited in tracking my movement. Formerly a sleep monitoring device, Lark was relaunched in April 2015 with full Apple Watch integration. Without one, the only activity and sleep tracking source I can choose is my iPhone Motion Sensors. This app is sexist and elitist, I think. Its developers actually think that every time I get up I have my phone on my person? (Maybe if I were a man with oversized pockets.) Or own an Apple Watch? (Maybe if I made more money.)

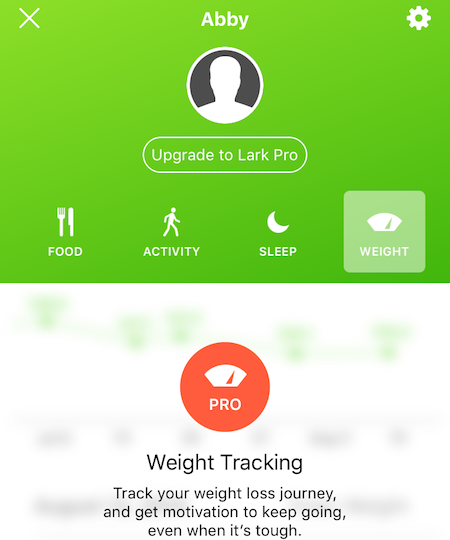

Next, when I click into “Customize my coach,” I’m only given the option to switch to metric units, alter Lark’s chat speed, and alert the app that I’d like to lose weight. Beyond that, I can’t find anywhere to actually log my starting weight. I don’t see any pricing information, and all of the reviews I’ve read tout the app as free and say nothing about upgrading for weight loss features.

I toggle about some more, my breathing increasing its pace some. Here I am, inside a chat app, with no agency to ask the most basic questions about how the product works. I get only pre-canned responses to choose from. When I visit the company’s website, I click on the Contact Us button, which takes me to a form to fill out if I’m looking for an enterprise demo. No humans in sight, I promptly close the app and ignore it for the rest of the day.

Day 3, Saturday, April 23

It’s 8 a.m. on a weekend and Lark already comments it “hasn’t seen much activity from me yet, but that’s OK because it’s typical of me for a Saturday.” Is it too early to admit that I hate this thing? I want to throw it a punch in the virtual face.

Ah yes, I’m getting incensed by a chatbot. I tell my boyfriend and he says I’m assigning too much tone to Lark’s messages and that I should give it a chance to be helpful. He’s one of those people with a Fitbit who is thrilled when he gets a new virtual badge telling him he’s walked the length of Italy or climbed enough steps to summit the Tower of London. I’m not into that stuff and so far I find Lark demoralizing. I huff around our apartment some, mumbling to myself about the absence of humans behind this bot. Maybe I am lazy. Maybe I’ll eat ice cream in this bot’s faceless face.

When I calm down and return to it, Lark again recaps my average activity and offers to share thoughts about how I might increase it, allowing me to text things back in response like “How so?” and “I see.” It’ll nudge me when I’m dipping low and congratulate me when I’m bumping things up, it says, before signing off with: “Enjoy the rest of your day.”

I close the app and log back in to see if I can prompt another conversation, but it’s nothing more than a repeat. The same comments about my low activity, the exact same wording and available responses from me–restricted to tapping “OK” in one instance and “Yep” in the next. I’m annoyed. I close it again and decide to focus on what Lark has told me to do today. Walk!

I check back in again in the afternoon and am informed my activity level is still sub par. (I haven’t yet manually logged the two-hour hike I’ve just taken.) When Lark asks if I’d like a tip for being more active, I say yes and it suggests that I drink water from a smaller glass so that I’ll have to get up more often to refill it. It calls that a “life hack.” It’s pretty obvious that this chatbot thinks I barely move from my couch to the kitchen sink. The most grating part about it is that I can’t give feedback. If I were on an automated call right now, I’d be yelling “agent, agent, agent!” at the top of my lungs. If I weren’t on assignment, I’d delete this thing altogether.

Now it’s time to get serious, though–and by that I mean throwing down the big bucks. If I really want this thing to talk to me about more than how little I move, then I need to get open access to its food logging/weight tracking function and analysis. Here’s what I’ve learned so far: If we want the best our chatbots have to offer, we’re going to have to pay for it. After a few moments inside the iTunes store and agreeing to a $19.99 monthly charge on my credit card for the app’s pro version, I’m rolling.

Day 5, Monday, April 25

Now that I’m a paying customer, Lark promises to deliver a 16-week, personal weight loss plan. The goal is sustained weight loss at one pound per week. I can choose a diet preference–vegetarian, vegan, paleo, low/no carb, dairy free, gluten free–and can opt in to have it “push me more” than it normally would any of its other one million users.

I’m psyched. I’m ready. Lark signs off and tells me to have a good evening.

Again, without receiving specific direction about what I’m supposed to eat or not eat, or even how much of it, I’m unsure if this chatbot has a plan. I scroll into settings and see that I’m supposed to aim for 60 minutes of activity a day. Otherwise, there’s no other manual of tips for how to lose a pound a week. I see that my weigh-in days are Sundays.

Later, I get my first push notification from the app. It’s noticed that I haven’t been very active in the afternoon and suggests I schedule an evening walk. What’s new?

Day 11, Sunday, May 1

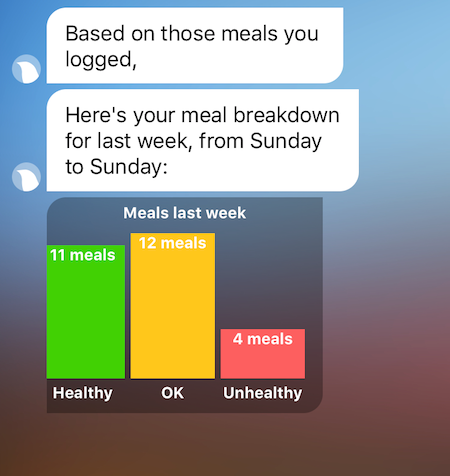

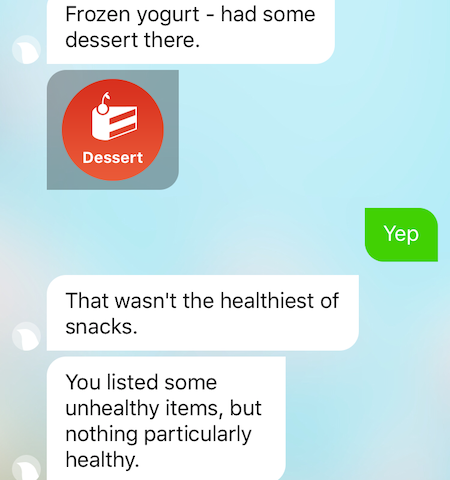

Over the course of seven days, I log the majority of my meals. I eat Domino’s pizza and a pint of Ben and Jerry’s frozen yogurt. I also eat a good deal of kale, lots of Greek yogurt with fruit and flaxseed granola, and grilled chicken.

When I get more diligent about logging my walks, which honestly I do feel compelled to take more of to hit Lark’s suggested activity benchmarks, I start beating my 60-minute daily goal. One day it’s by 16 minutes and Lark is proud! Another day it’s by 44 minutes, which is well above the 50-minute average that most people get in, it says.

Finally, Lark explains (a bit vaguely) that it’s initially interested in the quality of the food I’m eating, not the quantity, saying that recent research suggests the most important thing for weight loss is the kind of calories–or types of foods you eat–more than the exact number. Obsessing over every calorie isn’t sustainable. It’s collecting my data over time and will be better equipped to offer suggestions based on the foods I eat regularly.

So, the app’s working off newer research that suggests the calorie is a pretty broken measure when it comes to dieting successfully and concepts of mindful eating. I can dig it–I just wish I had been privy to the operating objective much earlier in the process.

Overall, in fact, I find the app’s advice much too general and nonrestrictive. (Eventually, it does ask me to give it feedback on how Lark could improve–go figure, this part allows for a free-form response from me meant for human eyes.) When I wake up tired, having gotten less sleep than usual, it reminds me to eat lean protein, drink lots of water, and avoid refined sugars. I dismiss the advice later in the day and eat way too many Twizzlers–in this case it’s not that the advice wasn’t good, it just wasn’t delivered to me in a way that I can associate with any real consequences. It’s possible that Lark and I have started off on such bad footing that our virtual relationship is irreparable. Chatbots don’t apologize.

Day 25, Sunday, May 15

After nearly a month of daily checkins, it occurs to me that my dislike for Lark is less a critique of one particular app and more about negotiating the evolving relationships between humans and chatbots. No doubt we’re heading in a direction where AI assistants will be everywhere.

What I learned from dieting with one is that we’ll be best served by exercising patience as we wait for information. Unlike dealing with a human–at least one who’s competent and listening to you–the answers we seek from chatbots will have to come in time. AI developers are smart, but they can’t anticipate everything users will need and in what order. All the information is loaded and there; the agency for getting to it just isn’t yet.

Lark co-founder and CEO Julia Hu said about designing Lark: “We basically cloned tens of thousands of conversations and interventions that these health experts knew would be effective in helping people get more active and eat healthier and sleep better.” Maybe tens of millions of conversations are in order.

The age of chatbots, it seems, will also force some of us to take a deeper look at ourselves and our own personalities. Maybe chatbots aren’t the answer for everyone when it comes to normally regimented tasks like dieting. I, for one, hated being reduced to six one-word answers in the course of a “conversation”–even if it was with a bot. Me, monosyllabic? Never. And more often than not, I interpreted the text messages I received in the app as intoned with negativity, though clearly they weren’t designed that way.

Nonetheless, why was I getting so angry at a bot? How was I feeling so unsupported by artificial intelligence? What’s wrong with it may not be the lasting question here.

On Sunday morning, day 25, I get on the scale and weigh myself.

“I saw you logged your weight. Would you like to talk about it?” Lark asks me. My answer can be one of two options: “Sure” or “Nah.”

I tap “Sure.”

“OK, cool. Looking at your overall trend, your weight is about the same as when we started. But what matters most is that you’re making a real effort,” it says. There’s one option for me to respond. I have to move on, so I take it.

“Thanks,” I tap.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Talking With Bots section, which asks: What does it mean now that our technology is now smart enough to hold a conversation? Click the logo to read more.