I can’t tell you where I lived between May 1988 and August 1991.

It’s not that I’ve forgotten. I was living in Kinshasa, in what was then called Zaire and is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. Our house was in an area called Binza and was perched on the side of a hill off one of the area’s many dusty lanes. But beyond that? I can’t tell you more, because there’s no more to tell.

“We didn’t really have addresses,” explains my mother when I first ask if she has any records of where we lived at that time. “Mostly, you followed someone who knew the way the first time you went anywhere. Or you drew maps for people with odd landmarks.”

So, I begin a quest. Surely, with the technology we have today, I’ll be able to find the place where I spent a major chunk of my childhood. I send messages to both of my parents asking for more detail, try to get in touch with the British Embassy in the country (where my father worked at the time), and download Google Earth so I can pore over satellite images.

My situation is far from unique. There are about four billion people around the globe who don’t have a way to refer to their home, and for every single one of them it’s a major problem.

No address means you’re essentially invisible to the state. Aid, legal rights, voting, and bank accounts are all outside of your grasp. It’s nearly impossible to start a business legally, let alone get anything delivered to that business. In an emergency, where do you direct the ambulance?

“Having an address is the first step on the social and economic development ladder. It’s a fundamental life issue,” said Giles Rhys Jones. He’s the chief marketing officer at what3words, a startup that’s aiming to establish an entirely new global addressing system.

“We’ve divided the world up into three-meter squares,” he explained. “There’s 57 trillion three-meter squares in the world, and we have an algorithm that’s allocated each one of those squares a three-word address from the dictionary.”

For example, the southern entrance to the White House is located at librarian.candle.complains. The spire of one of Egypt’s great pyramids is at being.everybody.smile. I broke my first bone at reply.eggs.tennis and met my partner for the first time at the excellently named options.probable.improve.

You’re probably thinking: “Don’t latitude and longitude already do that?” The answer is yes, but three words are far easier to remember than a long string of numbers. The system works in 10 languages, and there are official iOS and Android apps that allow you to look up anyplace on the planet. The company also offers an API that other navigation services can plug into.

Given the difficulties that programmers face when trying to deal with addresses, it’s no surprise that what3words is proving popular around the globe. “We were used at the Super Bowl for emergency response,” said Rhys Jones. “We’re being used in Lake Tahoe for ski patrol. We’ve even been used to label fire hydrants in Colorado. They’ve got 57,000 fire hydrants–all have got a three-word address now.”

As I keep hunting for my childhood home, the thought occurs to me that it might not even be there anymore. The Democratic Republic of Congo has endured near–constant conflict since I left in 1992. Has it been demolished as part of that fighting?

Or, if not, perhaps it has fallen victim to the endless urban renewal that takes place in many major African cities. It may have been knocked down for construction materials to build a nearby apartment building, or become derelict and overgrown by plants. If there’s one thing you can count on in Kinshasa, it’s that vegetation will engulf any structure left unattended for a year or two.

In various emails with my parents, they write of the Route de Matadi, a major road that snakes from the shore of the Congo River in the north, all the way through the western half of the city to its southern suburbs. So that’s where I focus my search. My dad says he remembers a sharp left-hand turn, but the city is full of sharp turns. I find an area with a lot of swimming pools that seems likely, but despite crawling back through more than a decade of satellite photos, I still can’t identify any houses that look right. My search continues.

Many governments have tried to roll out a street addressing system, and in almost every case they’ve dramatically underestimated the scale of the task. “It takes a lot of time and it costs a lot of money,” said Rhys Jones. “You’ve got to individually go round every single street and every single household and allocate something to that, while they’re constantly changing.

“Ireland just put in eircodes, which is their postcode system–that cost, I think, 28 million euros to put together and took 16 years or so,” continued Rhys Jones, adding that Ghana has endured four different attempts to set up an addressing system. “Every single one has taken a long time, so someone else has come in and said, “‘Let’s scrap that, let’s do this system instead.’ We’ve got images of a house with four different addresses on its wall.”

The problem isn’t rural, either. According to what3words’ statistics, 50 percent of those living in cities don’t have a street address. With 70 percent of the world’s population expected to be living in cities by 2050, that problem is only going to get worse. “A lot of the ‘smart cities’ initiatives are looking at 10, 15 years down the line when everything’s going to be able to talk to each other and everything will be brilliant,” Rhys Jones said. “Yet, we still haven’t solved this big fundamental issue, which is that people can’t tell people where things are in an easy way.

Breakthrough. I wake up one morning to a message from my dad:

I think I have found it at last.

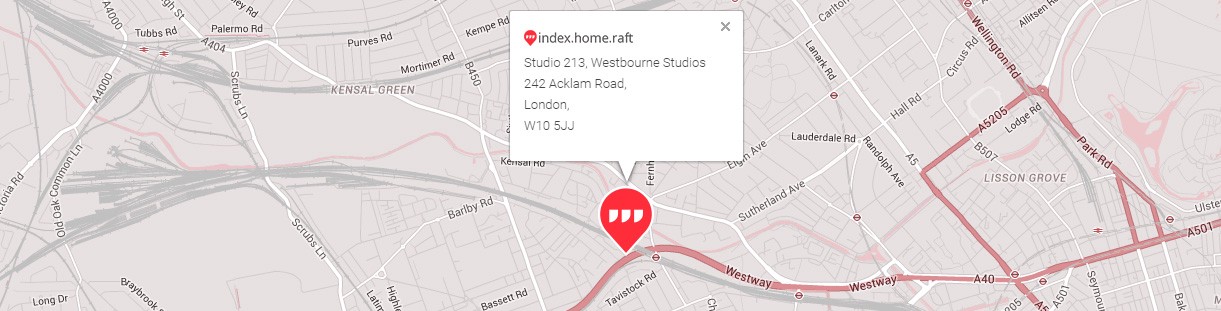

On Google Maps: Proceed from downtown (Bld 30 Juin/Mondijiba) past the golf course and on to a junction where you see Kintambo Magasin. Take the Avenue Nguma/Devinière and follow it all the way up and round a sharpish left hand bend where you see Belair. Then take the first right: Ave Belair, a dirt track with a rather pretentious name! Switch to Satellite. Proceed down Ave Belair and find the first house on the right with a swimming pool. That’s not it. It’s the house before that with a rectangular grey bit (the swimming pool) at a diagonal to the “‘road’. Eureka. Now, in return, you can tell me what this is all about!

Love Dad x

I anxiously load up Google Maps and follow his directions. I locate the golf course, Golf De Kinshasa. My thumb traces down the road past Kintambo Magasin and then along the Avenue Nguma, which appears to be named after a cryptozoological hippo-slaughtering lizard with a neck “as thick as a man’s thigh.”

The sharp left turn is there! It winds around the back of the Palais de Marbre, the place where President Laurent-Désiré Kabila was assassinated by a child soldier on the afternoon of January 16, 2001. Ten days later, his son Joseph Kabila was sworn in to replace him–with the backing of Robert Mugabe and the parliamentarians that his father had more or less handpicked before his death.

Mildly alarmed that this all took place so close to where I used to live, I swing down Avenue Belair and track down the first house on the right with a swimming pool. I back up one house, as my dad instructs, and it’s there. My childhood home–still standing–and as far as I can tell from the aerial photo, wholly intact.

There’s no street address, so I load up what3words and carefully position the marker over my old bedroom. pack.grows.joyously, it tells me. Yes, it does.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Metropolis section, on the way cities influence new ideas–and how new ideas change city life. Click the logo to read more.