The Associated Press auto-generates over 1,000 stories per month using a bot called Wordsmith. It’s not alone. Major media companies such as The New York Times, Le Monde, Forbes, and the Los Angeles Times have been automating news content creation for a while now. The news we read is already written by robots, and the wider public doesn’t seem to have noticed.

The technology holds a lot of appeal for publishers. Journobots are able to generate news faster, with fewer errors, and at a larger scale than human writers. At AP, automation has freed up 20 percent of the staff’s time across the business desk. Automated content in multiple languages, personalized to an individual reader’s preferences, is now not only possible but gaining popularity at outlets around the world.

But bots aren’t perfect. They get things wrong, and failing to hold them accountable in the same way we do human writers could have vastly detrimental consequences for our democracy. In order to harness the power of journobots, checks and balances must be put in place. An independent authority needs to be created–an algorithmic ombudsman.

Right now, it might surprise you to learn that the full extent of the use of journobots is totally unknown. When Bloomberg’s editor-in-chief John Micklethwait announced in April that the media group is creating a 10-person automation team, he described this field as a “wild west.”

An increasing number of companies make robots that produce automated text: Narrative Science and Automated Insights in the United States; AX Semantics, Text-On, 2txt NLG, Retresco, and textOmatic in Germany; Syllabs and LabSense in France; Arria in the United Kingdom; Tencent in China, and Yandex in Russia. Many of these companies have declined to provide information about journalistic clients, citing non-disclosure agreements. But shouldn’t we know more about who’s writing our stories?

Another problem is that journobots are subject to less oversight than human writers. The majority of AP’s automated stories go live on the wire without an editor’s review. For the moment, these automated stories tend to cover financial earnings, weather, and sports reports–factual topics, simple in nature with regard to data analysis. But what will happen when journobots start reporting on more complex issues?

Research has shown that people actually find it difficult to tell whether an article has been written by a robot or a real journalist. A recent study carried out at the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich revealed that readers rated texts generated by algorithms as more trustworthy than texts written by real journalists, especially when they were unaware that the algorithmic text had been written by a bot. Articles which the participants falsely believed to have been written by human journalists were consistently given higher marks for readability, credibility, and journalistic expertise than those flagged as computer-generated–even in cases where the real author was in fact a computer.

Should we be concerned?

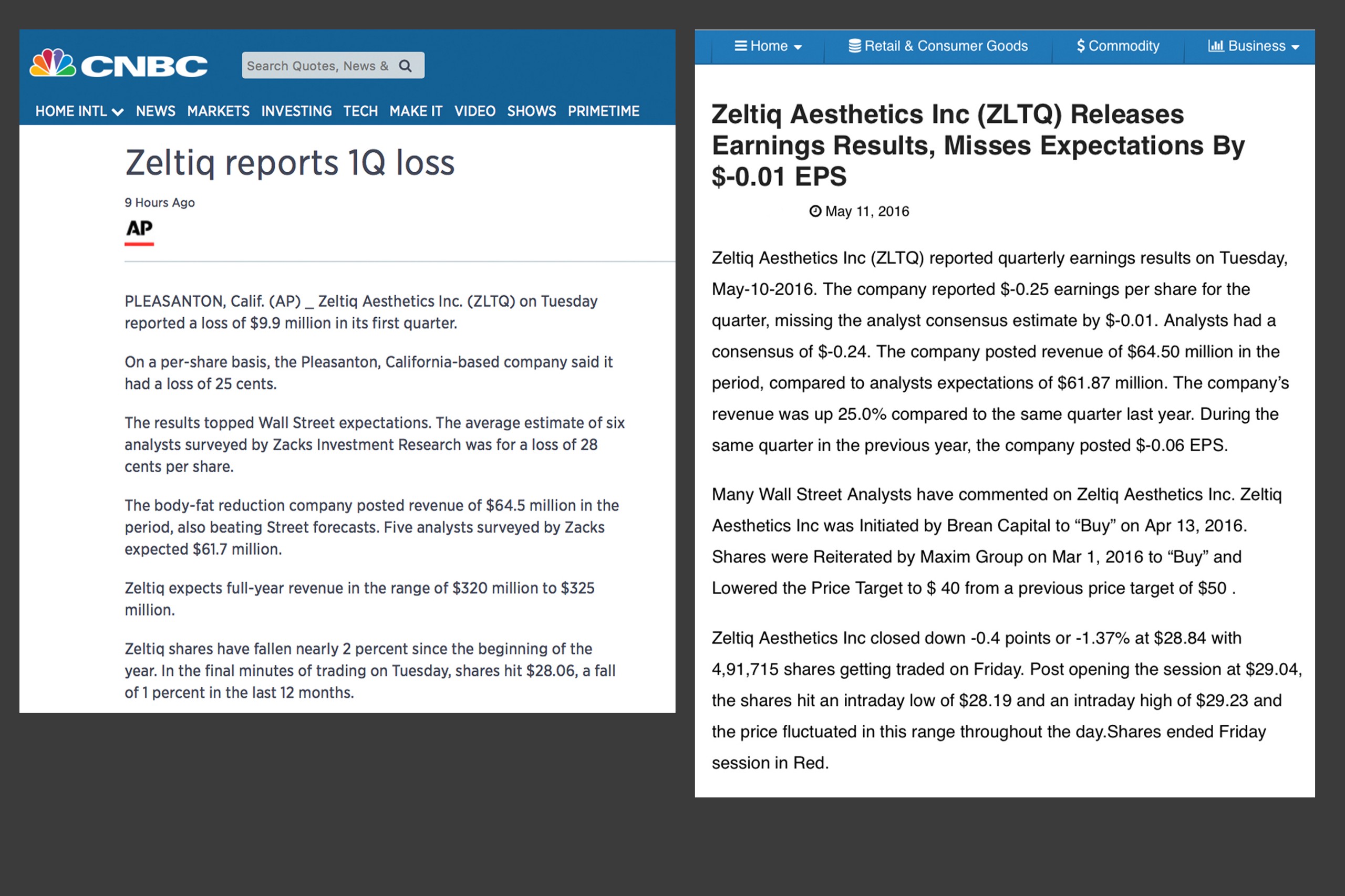

Bots get things wrong on a regular basis. In 2014, the Wikipedia Live Monitor–a bot that scans Wikipedia edits to synthesize the breaking news of the day–sent out a tweet saying that an article about the death of NBA player Quinton Ross might qualify for breaking news. It was true that a man by the same name had died, just not the basketball player.

In July 2015, Automated Insights’ bot Wordsmith reported wrong quarterly earnings for Netflix, causing substantial embarrassment for the Associated Press. In fact, a simple Google search for corrections posted by the AP on its Automated Insights stories yields thousands of results.

“Mistakes do happen, though it’s not clear how often and how severe those errors are,” said Nicholas Diakopoulos, an assistant professor at the University of Maryland’s College of Journalism and a worldwide expert on algorithmic accountability. Because of the way some stories are syndicated, uncorrected versions persist online.

Even when the bots get things right, hackers can target their algorithms. “We’ve already seen online crime gangs trying to hack newsfeeds in order to affect stock prices for their benefit,” computer security specialist Mikko Hyppönen told me. “Algorithmic news will certainly be targeted by similar attacks.”

Beyond robotic authoring, algorithmic editing is also fast becoming an issue. Bots have the ability to set the news agenda. As publishers have lost control over news distribution, social media, search engines, and personalized news aggregators such as Google News are increasingly deciding what the public reads.

Media’s democratic power–the so-called Fourth Estate–to monitor political workings and prevent political players from abusing the democratic process becomes blurred if robot journalists take over part of this watchdog role for government and corporate misconduct. With the issues identified above, we need to ask ourselves–can we trust them?

Implications for the news industry

There is little dispute that news organizations need to ensure that their use of robot journalists is done in a safe, ethical, transparent, and accountable way. There must be processes and standards to test the accuracy of the automated news they produce.

Diakopoulos, for example, has already suggested the disclosure of several aspects relating to human involvement, the underlying data, the model, the inferences made, personalization, visibility, and the algorithmic presence.

It shouldn’t be too difficult. Media organizations’ desire to maintain trust and legitimacy with the publics they serve should already encourage them to be transparent about their use of algorithms and data. But Andreas Graefe warns that the low profile of the role algorithms play in journalism means that there isn’t yet widespread public pressure for disclosure in this regard.

“The New York Times, FiveThirtyEight, and BuzzFeed have led the way in being transparent,” said Diakopoulos. Others should follow as expectations increase.

The bot-makers also bear some responsibility. While it’s impossible to wholly remove bias from algorithmic systems, designers and engineers can be more conscious of their role in creating those systems. Readers should be given the opportunity to be aware of the bias profile of different algorithms when choosing what to read.

To make that possible, there need to be standards on how to report and present this information. Diakopoulos is an advocate of benchmarking algorithmic systems on standard data sets and making those benchmarks public. “We should set standards when democratic processes, or where people’s health or safety might be put at risk,” he said.

An algorithmic ombudsman

To meet these standards and ensure that algorithmic–and ultimately democratic–accountability is applied, we need an algorithmic ombudsman.

This ombudsman would safeguard the public’s interests, supervise the implementation of proper journalistic ethics, and guarantee that the use of bots is fair, transparent, and, above all, responsible. It would inform about the degree of algorithmic bias, examine critical errors and omissions, intervene, and arbitrate.

Most crucially, an ombudsman would help build trust among the public and powerful platform operators such as Facebook and Google. The algorithms behind these platforms act as editors, commanding immense capabilities to determine what users see. Already, this is causing problems–the recent accusations of Facebook employees suppressing conservative news, forced the company to deny allegations of bias, but more importantly raised widespread questions about the algorithmic censorship of its newsfeed.

Some believe that governments should play a role in enforcing these standards. Others think that these ombudsmen should sit within companies, taking over the role of a public editor. Either way, robust debate must happen.

Bots in the loop

The chief benefit of the creation of an algorithmic ombudsman is that it would allow us to fully capitalize on the collaboration between journobots and real journalists. Jens Finnäs, who is responsible for developing Marple, a Google-funded automated news service, told me that robots can put journalists “in the driving seat,” allowing them to look at the data as a whole to find the most news-worthy signals, instead of relying on pre-packaged information selected by corporations and PRs.

“A “‘human in the loop system’ demonstrates how technology can be useful to journalists,” agreed Meredith Broussard, a fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism. Broussard is building a Story Discovery Engine “to uncover potential campaign finance fraud,” and hopes to have it launched by the summer so people can use it to report on the upcoming U.S. presidential election. Her project is a good example of how journobots can help democratic accountability, rather than obstruct it.

Now how about we unleash the journobots against Trump?

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Talking With Bots section, which asks: What does it mean now that our technology is now smart enough to hold a conversation? Click the logo to read more.