Steak has always been more than just food. It is a symbol–of masculinity, of power, of the authority of the United States of America. When Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, a Republican, told supporters in September that his opponent, the Democrat Beto O’Rourke, wanted to replace barbecue with tofu, he struck such a cultural chord that it made national news. In her 2016 book Meathooked: The History and Science of Our 2.5-Million-Year Obsession with Meat, Marta Zaraska writes of the food’s power as a symbol: “Recent scientific studies confirm that those of us who hold authoritarian beliefs, who think social hierarchy is important, who seek wealth and power and support human dominance over nature, eat more meat than those who stand against inequality.”

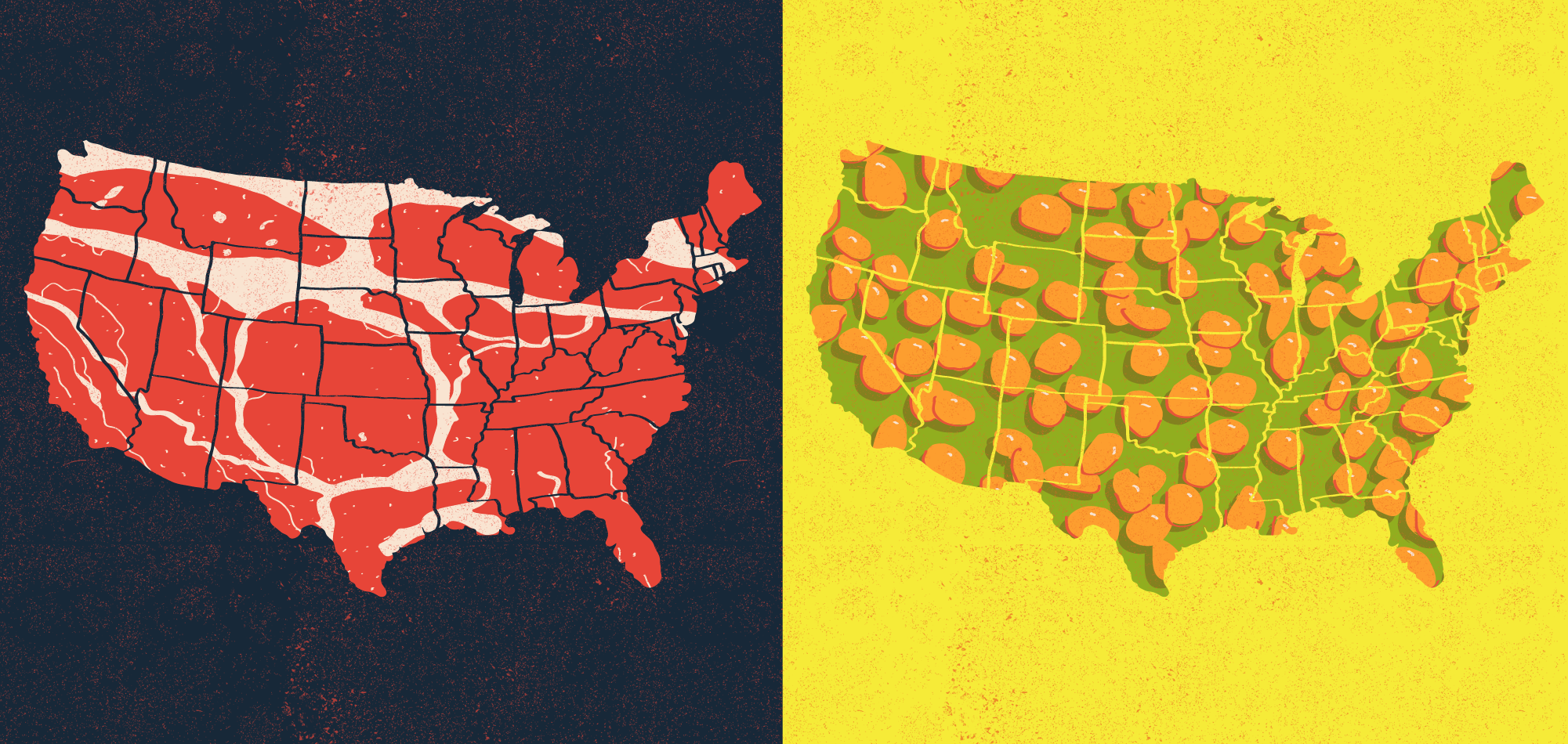

But if O’Rourke did want to replace meat with tofu–though from his many visits to the state’s fast-food chain Whataburger, it doesn’t seem so–he’d be on the right side of science. A 2017 study published in the journal Climatic Change found that if everyone in the United States substituted beans for beef, the country could reach up to 74% of the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions needed to meet the 2020 goals set by President Obama in 2009. In light of the United Nations’ dire 2018 climate change report, released on October 7, one might hope to see a seemingly small but culturally fraught change to people’s diets pushed more forcefully. Instead, vegetarianism and veganism have long been painted as individual consumer choices that cannot make a real dent in the disastrous situation in which the human race finds itself.

It is true that the only real solution to climate change requires massive long-term changes to our political and economic systems. It requires revolution. Many of the people with real power to prevent the most catastrophic effects of rising temperatures are the same billionaires who have ways of profiting from total disaster. “A top JP Morgan Asset investment strategist advised clients that sea-level rise was so inevitable that there was likely a lot of opportunity for investing in sea-wall construction,” notes an October, 2018, GQ article. Government regulation and action have a role here, insofar as they can exert control over the 100 companies that are responsible for 71 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

When the science as well as the socioeconomic and political reality all back the idea of hopelessness, why change anything about how one lives in the day to day? What use would it be to suffer through a plate of beans when there are still steaks at the grocery store–grass-fed ones, even?

There is a case to be made, though, that one’s eating habits can be part of a powerful collective movement, and can provide an opportunity for worker solidarity and anti-corporate activism. Even someone who believes in eating meat and other animal products can presumably understand that the reliance on centralized, factory-farmed production of meat and dairy creates the potential for growing food insecurity. Slaughterhouses are also gruesome workplaces that employ mainly immigrant laborers, and many facilities are perpetrators of environmental racism, as they are often located in low-income communities of color.

A new book from Carol J. Adams and Virginia Messina, Protest Kitchen: Fight Injustice, Save the Planet, and Fuel Your Resistance One Meal at a Time, makes the argument that how you eat is a significant form of protest against capitalism, the patriarchy, racism, and environmental destruction. Adams (author of The Sexual Politics of Meat, the seminal vegan text connecting patriarchy and meat consumption) and Messina connect the potential impact of veganism-as-boycott to the actions of 18th- and 19th-century abolitionists who refused to purchase sugar from slave-owning nations. Amid the recipes for cakes, stews, and energy balls for protest days are succinct arguments for the connections between the consumption of animals and many other ills–climate-based and otherwise.

The subtext is that a truly progressive person cannot support an industry built upon the exploitation of workers, the environment, and animals. That has become even clearer since the release of the UN’s 2018 report on climate change’s effects, which states that “the most affected people live in low and middle income countries, some of which have already experienced a decline in food security.” What we eat is no longer a matter of consumer choice but of global health, both human and environmental, with historical precedent for potential political impact. Within the confines of capitalism, our dollars are a powerful form of speech. And because we must necessarily spend those dollars on food–we still need to eat to survive–why not make this staple purchase speak for us?

I haven’t eaten meat since 2011, for reasons ecological, political, ethical, and even spiritual. It’s easy for me to tell people to eat beans and not beef: my consciousness shifted over a luxurious length of time; my health and bank account have never forced me to choose convenience over conscience; and I learned how to cook as a hobby, something I’ve had time for since I don’t have children or other dependents. But I didn’t stop eating meat because of an aversion to the taste of pulled pork and chicken tenders. I stopped because it was a decision that didn’t demand much of me and would have an undeniably positive, if tiny, impact on a warming world.

There’s recent precedent for the effects of a concentrated, collective demand. Before the UN climate report, U.S. environmental news this year was focused on plastic straws–roughly 500 million are reportedly used in the United States daily, and they often end up clogging waterways and hurting aquatic life. At first, it was a matter of broad agreement: Why shouldn’t we stop using so many plastic straws? It’s inarguably wasteful and destructive, and they’re not necessary. Then there was the reasoned backlash: some people with disabilities need plastic straws, making this is a matter of accessibility. Still, the city of Seattle banned the straws, and some companies have pledged to rid their stores of them over the course of the next several years. For the most part, this was a movement that everyone could get behind, a rare case in which a push for a change to benefit the environment drew the attention of governments, corporations, and individuals.

But the original source of that 500-million-straw statistic is a nine-year-old’s estimate, and Eco-Cycle’s “Be Straw Free” campaign was sponsored by reusable straw-makers. Even though the entire moment felt manufactured, it somehow successfully gripped a populace that’s usually antagonistic toward changing individual behavior. Few other requests from environmentalists ever become such hot topics of conversation. Yet the science and statistics backing up the dire need for us to abandon factory-farmed beef are far less murky than the data supporting the straw conversation, which had its own animal rights component.

When plastic straws were still the subject du jour, many ignored (or simply did not know) the fact that eliminating fish from our diets would also have a drastic effect on the well-being of the planet’s waters. Fishing equipment makes up 46 percent of plastic waste in the ocean, and many marine species are overfished. Memes went around in vegan circles noting the incongruity of people’s newfound obsession with ocean health and their continued consumption of its residents. Yet extending concern to animals and the effects of eating them remained niche, as it always has. The work required to stem the world’s rising temperatures requires a cooling of tensions between ethical vegans, those who are apathetic to the plight of livestock, and everyone in between. Without such cooperation, humans will not prevent the kind of climate change-related destruction that has already affected vulnerable populations in Louisiana, Texas, Florida, North Carolina, the Caribbean, France, Hong Kong, and so on. Perhaps concern for the lives of people–if not cows, fish, chicken, or pigs–can prompt hungry omnivores to reach for beans.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This is part of our “Food” Beat, which covered the social, political, economic, and technological implications of food production and distribution. For more dispatches, click the logo.