After watching the Black Mirror episode “The Entire History of You,” a student in my information ethics and policy class asked if, in a world in which every action we take is recorded and every memory can be accessed, we would see an end to crime entirely. Or wait, she reflected after a moment, maybe the police wouldn’t have access to that information at all–wouldn’t it be an invasion of privacy? Actually, how might the Fourth Amendment apply, if it protects against unreasonable search? Another student jumped in and suggested that using your own memories against you would be a case of self-incrimination. A violation of the Fifth Amendment. Though, he added, he didn’t think that the characters in the show would be acting the way they did, either. We would obviously have to develop social norms to keep people from just playing their memories for each other willy-nilly.

The class was quickly divided, some taking the stance that privacy was of paramount importance, others suggesting that there might be some ways to take advantage of the technology to make people safer, if we were careful about how we did it. I reminded them that we’d had a similar conversation about whether the FBI should be able to compel Apple to unlock iPhones. Then I told them about the Supreme Court’s 1967 ruling in Katz v. United States, which established reasonable expectations of privacy with respect to phone calls.

These precise regulatory and ethical issues didn’t come up in that Black Mirror episode–but the mere idea of that futuristic implant proved a valuable catalyst for discussing the very same complexities we grapple with now. We might never see memory-sharing technology come to be, but we do have to decide whether someone’s biometric data via an Apple Watch or pacemaker can be used to incriminate them. Alexander Graham Bell likely did not anticipate that the telephone would lead to a landmark privacy ruling, and he would have considered a description of a Fitbit to be outside the realm of possibility. And the founders of Strava probably didn’t consider that their fitness tracking might reveal the locations of military bases. Today’s technology is yesterday’s science fiction. So even if we can’t accurately predict the future, can’t science fiction help us learn to be forward-thinking?

When the Future of Computing Academy recently suggested that authors of computer science papers should write about the possible negative implications of the technology they build or the research they conduct, one complaint I saw from scientists was that this would require speculation: How are we supposed to know what bad things might happen? This is a fair point, and also precisely why I think that encouraging creative speculation is an important part of teaching ethical thinking in the context of technology.

This is not a new idea, and I’m certainly not the only one to do a lot of thinking about it (e.g., see “How to Teach Computer Ethics Through Science Fiction“), but I wanted to share two specific exercises that I use and that I think are easily adaptable. And Black Mirror, too, is only one example. I’ve also used films (e.g., Minority Report and The Circle, although the book of the latter is better) and short stories (in particular some great ones by Cory Doctorow, like “Scroogled” and “Car Wars“). There are also books that would be fantastic–from classics like Ender’s Game or Snow Crash to newer books that I particularly enjoyed as an intellectual property nerd, like Doctorow’s Walkaway and Annalee Newitz’s Autonomous. It’s also important to remember to consider works created by women and by others that have been marginalized in science fiction.

Feel free to use these ideas any way you like–and if you teach technology ethics, you might find even more ideas in this giant list of curricula from others.

Exercise 1: Speculative Regulation

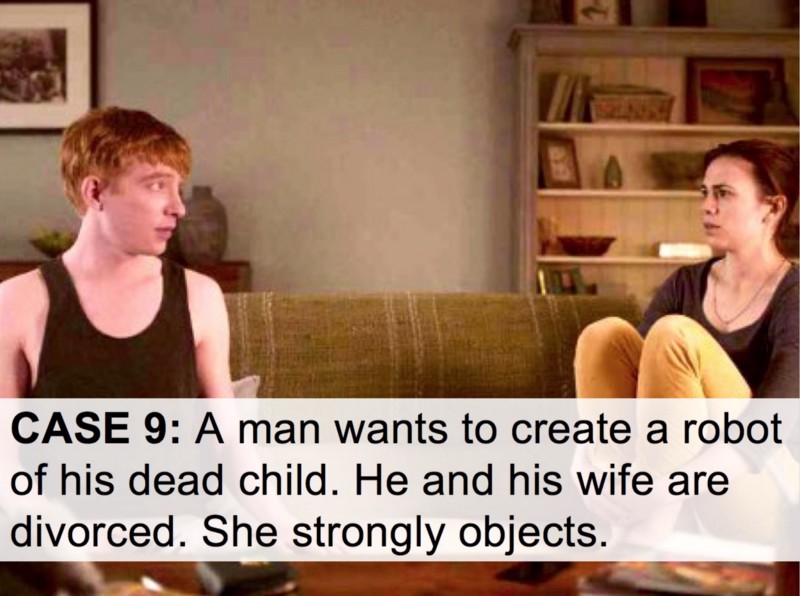

This is an exercise that I have specifically done with the Black Mirror episode “Be Right Back,” but it could be adjusted to work with any science fiction narrative about a future, pervasive technology (for example, “The Entire History of You,” as described above). I do think that it works best when the technology seems feasible, or at least represents a foreseeable straight line from our current capabilities. In “Be Right Back,” a young widow signs up for a service that creates a chatbot of her deceased husband from his communication patterns (which is technology we’re not far from). Eventually, an upgrade option leads to a re-creation of her husband in the form of an eerily lifelike android (which we’re much farther from, but you can see the straight line).

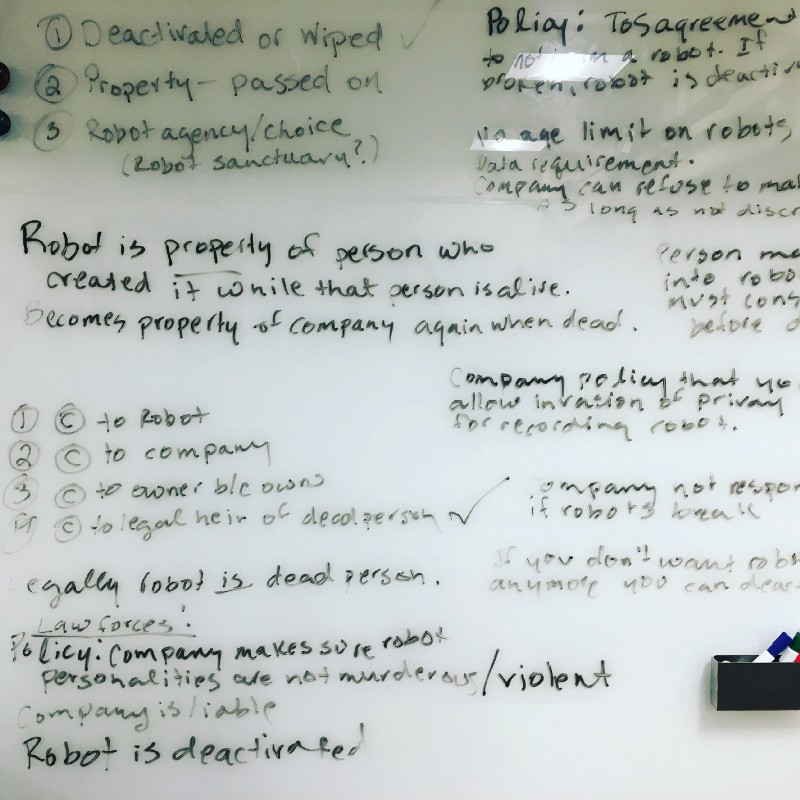

After a viewing of the episode, the exercise begins like this: What kinds of regulations would exist in a world that had this technology? In other words, if someone could “bring back” a deceased person in robot form, what current laws might regulate this practice, or what new ones would be created? What would the terms of service for this technology look like? What social norms would form? What kinds of ethical decisions would individual actors have to make?

A conversation seeded with these questions can be interesting on its own, but regulation and ethical norms are often reactive. For example, specific situations, like the Cambridge Analytica scandal and evidence of widespread online misinformation campaigns, have led to calls for new kinds of regulation for platforms like Facebook. A decade and a half ago, could we even have imagined that someone could and would use social media platforms to attempt to influence elections? Sometimes the crazy stuff needs to happen before you can start to see the design space. Not to mention that edge cases and counterfactuals can make for the most interesting discussion–in law school, “hypos” are a dominant pedagogy.

Therefore, in this exercise, I use specific hypotheticals to morph the conversation and get at specific regulatory and ethical issues. Can a robot have custody rights to a child? Are there consequences for mistreatment of a robot? Can a robot ask for a divorce? Who is liable for a robot’s behavior? Who is responsible for its care? Can a robot hold a copyright? If you want to use this piece of sci-fi, here is the slide deck that I’ve been using to propose these questions; there are tons more hypotheticals that you could add to it. (A student asked me how I came up with all these things. I responded that, as both a lawyer and a science fiction writer, I’m kind of uniquely trained for exactly this.)

By the end of the first class period I tried this exercise, my students and I had created some fairly complex regulations, including a number of provisions that would have to be part of the robotics company’s terms of service. It turned out to be a great exercise for thinking through conflicts between stakeholders, types of liability, and questions about who holds power.

Exercise 2: Black Mirror Writers’ Room

Most of my students have been aware of, if not seen, Black Mirror (though I will also typically use at least one episode in class, as in the exercise above). The best episodes tend to be the ones where the technology isn’t too outlandish–take something that we already have (like “When your heart stops beating, you’ll keep tweeting!“), and take it just a step further. Just on to the other side of creepy.

To encourage speculative thinking, I put students into small groups and assign each an issue we’ve covered in class–social media privacy, algorithmic bias, online harassment, intellectual property, misinformation. I ask them to take it just a step further. Where could technology or a social system go next that would be worthy of a Black Mirror episode?

Sometimes they come up with things that are right around the corner: What if predictive machine learning knows from your social media traces that you’re sick and sends you medication? (Or maybe Alexa can just tell from your voice.) Well, that’s not that creepy–but what if the technology weren’t just neutral but entirely profit-motivated, so that the program makes a calculation, based on how depressed you seem, as to whether it is more likely to make a sale when advertising antidepressants or heroin?

Or what if advertising didn’t exist at all? Once, a group contemplating privacy suggested a post-choice world: when our technology knows everything there is to know about us, it can just send us exactly what we need. (I suggested that a proper Black Mirror plot for this idea would be someone slowly becoming more upset about the invasions of privacy, and, at the end, an Amazon package appears at the door, containing a book titled So You’re Having an Existential Crisis About Privacy.) In another class, we riffed off of Cambridge Analytica, and ended up theorizing a “benevolent” AI that uses highly personalized content to manipulate the opinions and emotions of everyone on Earth, in order to keep the peace–until it realizes that the Earth is overpopulated, and things just get worse from there.

Of course, speculating about the bad things that could happen isn’t a great place to stop. The next step is to consider how we don’t get there. In class, this typically leads to conversation about different stakeholders, responsibilities, and regulatory regimes. I also specifically push the students to think about what technologists can do. It’s too easy to just say, “We should have laws for that.” Instead, what might the person involved in creating the algorithms or the AI do to take responsibility and prevent potential negative consequences?

I also encourage students to plot for “Light Mirror,” too. Where can technology take us that will benefit society and make things better? How can we get to those futures? To be fair, these plots tend to be less compelling–which is perhaps why the “evil tech” narrative in sci-fi is so common–but it’s a much more uplifting note to end on!

These exercises and ideas are all in service of the way I like to think about teaching ethics–that it’s about critical thinking more than anything else. There are rarely black-and-white answers for anything. And speculation is one way to start to see the gray areas and edge cases. To be clear, we shouldn’t actually be designing regulation for technology that may or may not arrive–I don’t think we have to worry about legislating a robot’s right to own property just yet. But if you can think speculatively about the ethical implications of the technology that someone else might create in 50 years, you can think speculatively about the ethical implications of the technology that you might create next week.

I hope that these ideas are useful for others in thinking through ethics in a learning environment! I also note that these exercises are not just intended for an “ethics” classroom–being able to creatively speculate is a great skill for technology designers anyway, which is one of the benefits of design fiction (see two examples of mine). And considering the possible negative consequences of technology should be part of everyday practice–after all, ethics is not a specialization!

Finally, it is important to remember that science fiction isn’t for everyone, and using it too heavily in a technological context can also serve to reinforce stereotypes. So be mindful, too, about both the producers and consumers of science fiction, and be thoughtful about its further implications. (Let’s face it, a lot of sci-fi is pretty problematic as well!)

There are a lot of important things we can be doing in the world to help, but I’d like to think that teaching technologists to think critically about responsibility and ethics is one way to keep our lives from turning into a Black Mirror episode.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Arts & Culture section, which looks at innovations in human creativity. Click the logo to read more.