“It takes 20 minutes to get cash into the hands of a North Korean,” said Jieun Baek, a fellow at Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Author of the forthcoming book North Korea’s Hidden Revolution, she estimates that somewhere between $12 to $20 million is transferred into the country annually from defectors living in South Korea.

Physical money isn’t actually moving at all, though–the foreign cash comes from stashes already inside North Korea. While smuggled loot once had to travel across borders, these days all it takes to initiate a change of hands is a phone call. In fact, so much foreign money moves from defectors to their families back home–through a complex network of remittances–that Sokeel Park, the research director at human rights NGO Liberty in North Korea (LiNK), has compared this new kind of banking to a “North Korean Western Union.”

For defectors living in South Korea (of which there are 28,795 as of 2015), the smuggling process starts with their reaching out to contacts in the diaspora for broker recommendations. Brokers are those with the connections to the communications channels between Koreans living in the Chinese-border regions and contacts in-country. “They find somebody who’s been reliable before,” said Park. “I personally know several people that have been able to send back, in their first year of living in South Korea, $5,000 “¦ even people just getting on their feet.”

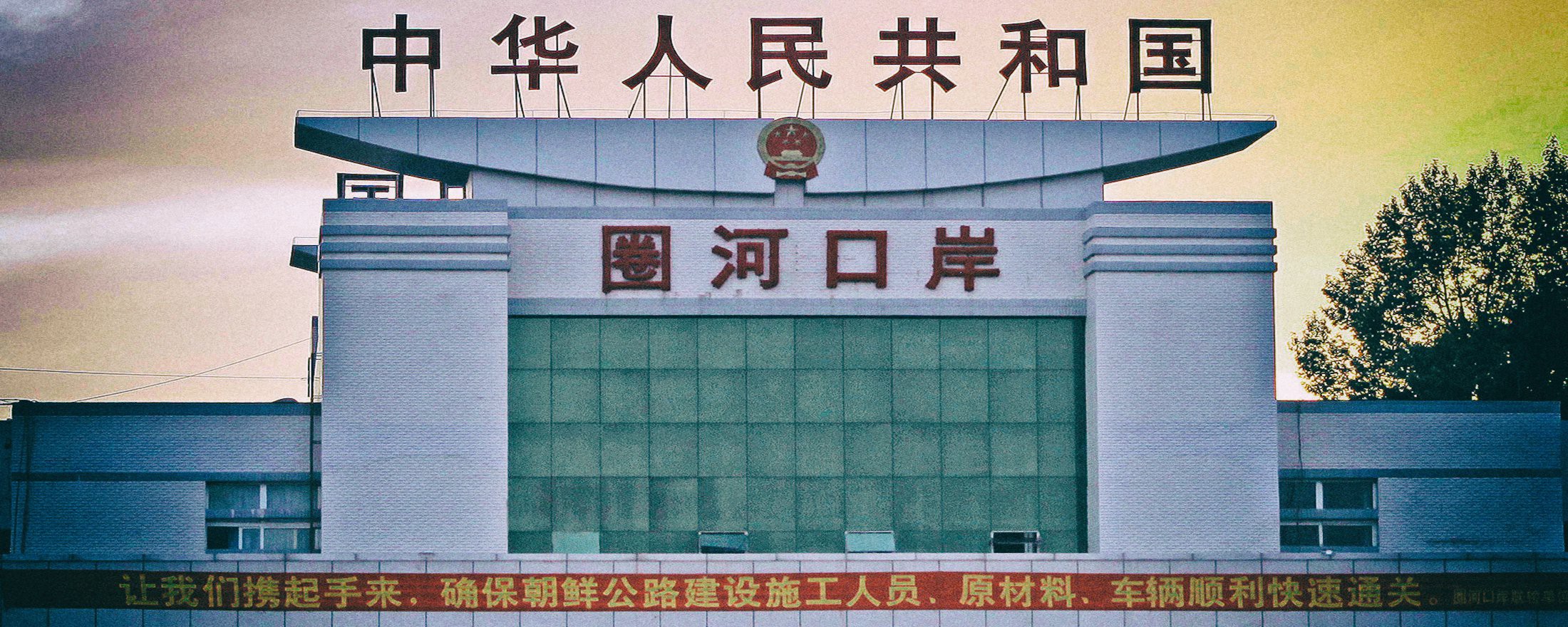

According to Baek, roughly 40 percent of North Korean defectors in South Korea hail from two provinces that share a border with China–Ryanggang and North Hamgyong. These residents wire money to banks in China, usually in Yanji, a city with a large ethnic Korean population. From there a contact in the community connects with a Chinese national in the DPRK–one with a Chinese bank account and a mobile phone able to contact the outside world.

Using a hypothetical transfer of $1000 as an example, Park explained: “This person is already sitting in North Korea. They can check their bank account in China using their mobile phone. You know, check that the money came through, and then take their own commission, which could be 15 percent, and pass the remaining $850 to a North Korean money courier.”

The courier then makes contact with the desired recipient, takes another commission and hands over the cash, which usually comes from a stash accumulated through private business–money which, of course, was also smuggled into the country,

“There’s a lot of people inside North Korea who are very wealthy right now,” said Baek. “We’re talking millions of U.S. dollars, which is extraordinary “¦ through business, over time, they’ve accumulated a lot of cash.”

In a world where banking is increasingly digital, it still pays to get your hands on hard currency. Millions of dollars are spent policing the international trade of illicit money across borders–smuggling that’s usually associated with drugs, weapons, and organized crime.

But foreign cash can also mean opportunity, a safeguard against state control and economic mismanagement. In Cuba, for example, dollars are preferable to the country’s devalued peso, and in Zimbabwe they’ve represented a necessary transition in a nation wracked by hyperinflation.

The use of foreign currency as a means for quiet revolution is no more prevalent than in North Korea. Even in the world’s most repressive and closed-off society, a private economy is booming as outside currency and cross-border banking become a necessary part of daily life.

Poverty is still widespread. But with a market increasingly free from the control of rulers in the capital city of Pyongyang comes the opportunity for spending–and the undervalued North Korean won just doesn’t cut it.

Much of this comes down to the complex way that money works in North Korea, also known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. The official currency in the country is the North Korean won, and, officially, you need 899.99 of them to buy one U.S. dollar–not a fantastic exchange rate even on the best of days. The accepted truth, however, is that its real value is much lower. Most every North Korean understands that trading on the official rate will make for enormous losses.

“There’s the unofficial rate, which everyone really accepts but does not publish,” said Daniel Tudor, co-author of North Korea Confidential, a book that examines the country’s underground economy. “Increasingly, you’re seeing salaries that are paid by state-owned organizations in numbers that reflect the real market value of the North Korean won–so, I think [the rate is] 8,000-to-the-dollar, or something like that?”

All this means that foreign currency, particularly the U.S. dollar and the Chinese yuan, is everywhere. Its use is common even in Pyongyang’s select department stores, where item prices are listed in both won and dollars. In some ways it seems the regime is adapting to the black market reality. It is being forced to.

The won has a history of unreliability, and still today many North Koreans remain dramatically debilitated by the government’s infamous currency devaluation of 2009. For the first time in 50 years, this saw the state crack down on the black market, wiping out the life savings of millions of citizens. Revaluation replaced 1,000-won notes with 10-won notes, while strictly limiting the amount of old currency that could be exchanged.

“One of the biggest things that has really taught the North Korean people to be cynical about local currency was the 2009 currency revaluation,” said Park.

The edict from Pyongyang was swift and brutal: North Koreans were given a week to exchange up to â‚©150,000 in hard cash (a rate estimated to have had an actual value of $30) and â‚©300,000 in savings.

This “was pretty unique in terms of fiscal policy around the world in that it was so clearly designed to actually disrupt the domestic economy and wipe out a lot of wealth that has been built up by market traders,” he added.

The move instigated massive public unrest, exacerbating the country’s dire financial state and provoking unparalleled protest. In true North Korean fashion, Pak Nam-gi–director of the government’s Planning and Finance Department–was publicly executed the next year in a demonstration linked to the revaluation failure. The government had managed to simultaneously undermine public trust in its national currency and show it was totally spooked by the growing market economy.

“There was too much change bubbling up, and a lot of that was driven by this new economic reality inside the country,” Park explained. “It seems like top-level policymakers tried to go back to socialism square one, not realizing that just wasn’t possible.”

This also had an enormous social effect: Those who had followed lessons drummed into their psyches from birth–”obey the rules and don’t question the state”–were left massively out of pocket, having suffered and saved through decades of famine and economic hardship only to lose everything after an arbitrary edict from Pyongyang. Those who had rebelled and kept foreign cash were safe. “People who hedged against government policy and government promises were able to protect themselves, or maybe even make gains,” he said.

Smuggled money is having a marked effect on the social fabric of once-impoverished communities suddenly flush with foreign cash. Indeed, a huge underground economy all amounts to money transfers that happen almost entirely with smartphones–and in such blatant defiance of one of the world’s most repressive regime. Despite the technology, though, it’s still a system largely based on trust: trust between the defector in Seoul and the contact in Yanji, and between the courier and the North Korean receiving the money.

So, what happens now? Well, for one the North Korean state is increasingly cracking down on cross-border communications and the use of “Chinese mobile phones” in-country in an effort to make it harder for these money transfers to take place. Still, foreign cash is already in the country. It just needs distributing.

“You hear a lot of very human stories of people sending money [to spend on presents and luxuries] on someone’s birthday,” said Baek. But even more, a lot of the smuggled money goes to building local business. If someone runs a market stall, for example, it can be used to hire more staff or invest in new facilities. “People don’t just receive $1,000 and sit on it and spend it little by little,” Park noted. “They’ll typically use it as some kind of seed investment and basically launder it through their business activities.”

And that’s to say nothing of the smuggling business itself. “If you’re a smuggler, you can buy more stock, you maybe employ more people, you do all the kinds of things a business person would do,” he added.

Hence, a growing open market. “If you wanted to accelerate positive change you’d get more information and more money to the North Korean people,” said Park. “And that’s exactly what North Korean refugees are doing.” They are smuggling money in a thoughtful, calculated way and this is “feeding the hotspots of change, which is more effective than a helicopter dropping cash randomly across the country.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Made of Money section, which covers the future of cash, finance, economics, and trade. Click the logo to read more.