A friend once told me that a defining characteristic of the 21st century is mass reliance on technologies and systems that we know are important but understand little about.

If this is so, electricity is a prime example of that. Without it, modern life as we know it would be impossible, but who can actually describe the path electricity takes to get to their home? How many of us know what happens before we plug our power cords into outlets?

I embarked on a mission to uncover the not-quite-secrets of the electric grid, the system through which electricity is supplied to us. I wanted to see if I could trace the route electricity takes to get from its source to my Brooklyn apartment. What I found was that the answer was just as complicated as it might seem.

To start with, what we call “the electric grid” is not a grid at all. It’s a system: an interconnected network of underground and overground infrastructur–poles, cables, transformers, substations, manholes–run by an assortment of organizations and companies.

The United States’ electric grid came into being in 1882 with the opening of Pearl Street Station, Thomas Edison’s ambitious effort to build New York City’s first power plant. Almost immediately, the potential of generating and distributing electricity was apparent to consumers and investors alike. Soon after Pearl Street Station’s unveiling, other plants and grids sprung up around the country.

Thus, the electric grid began as many individual systems, all operating in isolation from one another. Eventually, these systems merged together, but tell-tale fragmentations still exist today. The U.S. electric grid is currently an amalgamation of three systems: the Eastern Interconnection, which serves the eastern half of the country, the Western Interconnection for the western half, and the Texas Interconnection, which serves nearly all of the state of Texas. Each interconnection functions as its own independent machine, so while a home in Sacramento, California, is ultimately connected to the same system as one in Portland, Oregon, both are completely separate from my home in Brooklyn, New York.

Here’s the process behind the electricity bill that I, along with 8.4 million other New Yorkers, receive every month:

First, electricity has to be created. Electricity is a secondary energy source; unlike coal or oil, it can rarely be harvested directly from nature. Instead, it must be generated through the conversion of primary energy sources, a process that–as most people know–takes place at huge industrial facilities known as power plants.

While there are still some power plants in New York City (mostly along the waterfront of Astoria, in the borough of Queens), most of the plants that serve the city are located elsewhere. Some are in upstate New York, some in nearby states like Pennsylvania or New Jersey. Some are even as far away as Canada.

Regardless of location, the energy these plants produce is auctioned and sold daily on a wholesale market run by the New York Independent System Operator. This agency sets prices by the megawatt, the unit used for measuring large amounts of electrical power (one megawatt is enough energy to power 1,000 average homes). Electric utility companies like Con Edison buy electricity off the market at the cheapest prices they can find.

Con Edison has complete control over the transmission and distribution infrastructure in New York City (and in Westchester County, a northern suburb). The company not only purchases the electricity that most New Yorkers use, but also handles how and where the electricity flows to get to us.

In other parts of the country, this process is less monopolized, and even in New York City there is leeway. Consumers can, as some large institutions like hospitals or universities do, opt to bypass Con Edison and enlist the assistance of Energy Service Companies to buy energy for them. But it’s still impossible to avoid the Con Edison system entirely. Regardless of who does the buying, all electricity for the city travels through Con Edison infrastructure.

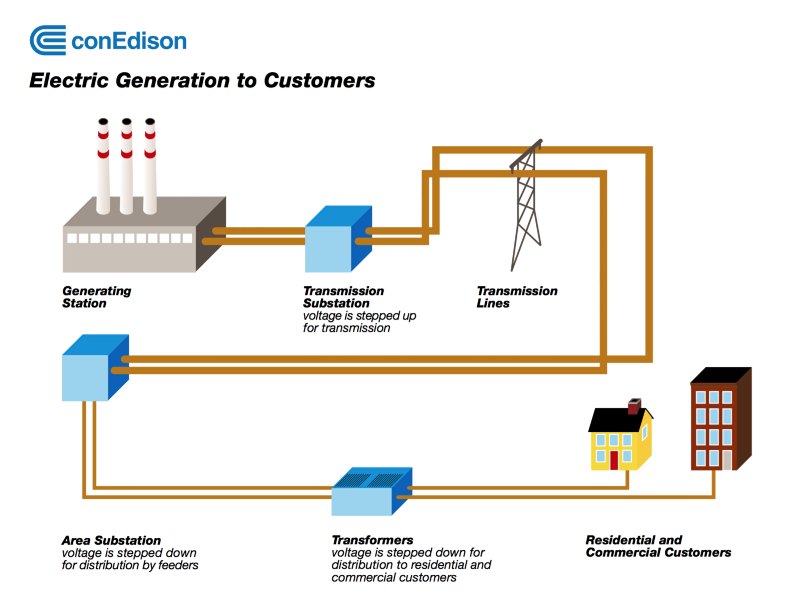

Once purchased through the market and received from generators, electricity flows to one of the city’s 39 transmission substations. These transmission substations are the first gateway for energy coming from long distances. Their role is twofold: first, to use devices called transformers to step up the incoming voltage (higher voltages transmit faster and are therefore cheaper); second, to pass electricity on to the city’s area substations.

The most “famous” transmission substation is located at East 13th Street in downtown Manhattan. It’s the substation that was struck and flooded by a 14-foot storm surge during Hurricane Sandy, resulting in about 230,000 people losing power. That number alone shows the impact transmission substations can have.

Area substations are where the real magic of the system takes place. Each substation serves one or more geographic sections (or “networks”) of the city. New York City has 62 of them, including those in Westchester. Area substations take the high-voltage energy coming through transmission lines and use transformers to step down the voltage. They then use feeders (cables) to distribute the electricity to homes.

For the electricity to arrive at its ultimate destination, it must pass through service boxes. Inside these service boxes, transformers step voltage down again so that it’s finally fit for consumer use. Connected to these boxes is the service itself, the cable through which electricity is finally piped into residential and commercial buildings.

To know where your electricity comes from is to know all the points it travels through: the generators that produce it, substations that route and distribute it, transmission lines that transport it, transformers that raise and lower its voltage, and the service that directs it into your home. But lest you think the process is as straightforward as I have described, I should mention that for each step there are further caveats and complications. Feeders are divided into primary and secondary; there are upwards of eight transformers in each substation; service boxes are also connected to manhole vaults that serve as access points to equipment; and power plants go by a plethora of other names (generators, power stations, powerhouses). Each step of the process could prompt its own exploration.

Instead of diving in deeper, however, I’ll explain a problem I came up against when trying to trace the power arriving at my home. Understanding the pieces of the system didn’t bring me any closer to knowing where my electricity came from. In fact, learning the intricacies of the grid only left me more clueless when it came to tracing the path of my power.

The problem is partly geographic–because of its huge concentration and dense population of people, New York City consumes massive amounts of electricity. But for the same reason, the evidence of that usage is rendered mostly invisible. With the exception of substations, most of the city’s electric infrastructure is underground. Some 94,000 miles of cable stretch underneath the blocks of the city. Throughout the five boroughs, our electricity, like our subway, moves below the surface.

This physical submersion is matched by the reticence on the parts of companies like Con Edison to reveal where their critical infrastructure is actually located. When I talked to Con Edison spokesman Allan Drury, he cited security concerns as the reason why this information is suppressed. In reality, the data function as an open secret–the information isn’t explicitly out there, but it’s not quite hidden either. There are ways to track down substations, and I could reasonably guess where the ones that serve my Crown Heights neighborhood are. But being able to locate the physical infrastructure couldn’t help me reliably trace the path of my electricity.

Herein lies the real reason for the inability to accurately trace my energy: Electricity for the entire system comes from a variety of generators and travels constantly through any number of cables, substations, and transformers. It’s impossible to isolate exactly where any home’s electricity started from or which particular stations it traveled through. I know that my electricity comes from some combination of power plants and travels through some transmission substations and cables to get to my nearest distribution substation. But there’s no telling which ones, and the power plants that Con Ed buys from change daily–according to the market.

Even if I could isolate the right starting place(s), there’s the further issue of how electricity in the grid is combined. Water makes for a good analogy: You can buy it from different sources, but if it’s all dumped into the same bucket, differentiation becomes impossible.

Even if you purchase your energy from renewable sources, as a growing number of consumers do, there’s no guarantee that you’re only receiving energy from those sources. If you buy bottled water and I purchase tap, but it all travels through the same complicated system of pipes and containers to get to us, neither of us would be able to tell the difference by the time it reached our glasses.

Ultimately, I was able to create some hypotheses about where my electricity comes from, and to deduce that if the farthest power stations in my grid system are in Ottawa, Canada, my electricity potentially travels up to 375 miles to arrive at my house from its source.

But it’s just that: a hypothesis, an approximation. It turns out that properly understanding electricity means understanding just how impossible to pin down it can be. The electric grid, as essential as it is, resists simplification. I can know and appreciate how electricity allows me to turn on the lights in my house with ease, but I can’t confirm how it got there.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Power Up section, which looks at the future of electricity and energy. Click the logo to read more.