My mother was an alien. I used to stare at her green card, its heading declaring her arrival from outer space, with “RESIDENT ALIEN” all in caps. I knew the story of how she arrived in the country, and I knew how she was known to others here. Black people have long been painted as “the other,” as alien. But it’s through our histories that we imagine our futures–and all of the new hope that may bring.

Afrofuturism is one way of seeing that future, where we can be assured of determining our destinies on our own terms. It’s a place where we are alien if we choose to be, instead of because someone else has labeled us as so. It’s a space where we embrace an alien landscape and make the technology our own.

Reproductive technologies such as in vitro fertilization (IVF) allow parents–who might otherwise be unable–to conceive and bear children. For a price, they can choose an egg or sperm donor, or even have a third party unrelated to the egg carry the biological baby of their dreams into being.

This sounds fantastic, like a marvel of modern medicine, until we realize that these technologies are often used along existing societal power lines of race, class, and wealth. For an example, take an episode of Radiolab from November 2015, called “Birthstory.” It chronicles a gay Israeli couple’s journey to having three children through finding surrogate mothers, through sourcing “cheap white eggs“–a phrase uttered to nervous laughter during the episode but otherwise not examined further.

It looks to be a heartwarming tale on the surface–a couple finds the necessary resources to have genetically related children. But take a closer look, and the view shifts to a more disturbing story involving “cheap white eggs” from a woman in Ukraine that are fertilized, the white fetus then implanted into an Indian woman in Nepal (a country where surrogate motherhood was still legal at the time; meanwhile, surrogacy for gay couples is banned in Israel). There are wider issues at work here–issues of class, financial power, transnationalism, and racial hierarchies–but they go mostly undiscussed in the service of presenting how wonderful it is that this technology is available for those that can afford it.

In this case, securing “cheap eggs” from an economically depressed white country and placing the resulting fetus into the body of a woman of color– who has chosen to rent out her womb for an acceptable price–mitigates the high cost of producing a white, biological child. It’s clear here that the couple’s desire isn’t simply for a biological child, but for a white biological child–something that’s a little eerie in practice when a woman of color bears a white baby simply because it’s cheaper.

In this example, women of color use their bodies to advance needs that aren’t their own, switching their bodies’ labor away from producing their own children of color to producing white children for others. Charis Thompson, the Chancellor’s Professor and Chair of Gender & Women’s Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, told me: “You could say that it’s great that people can have biological relations, for example gay couples, but if you don’t take a reproductive justice perspective, you don’t see the racial dynamics and socioeconomic dynamics that underlie every part of that.”

Here, children of color are devalued as compared to white kids (which is also borne out in the reality that black babies cost less to adopt)–a prospect that manifests itself in the ways reproductive technologies are used. In the present, as in the past, new medical technology isn’t liberating for everyone. More often, it’s used to advance the desires and dreams of white people, at expense to people of color.

We’ve seen this before, in Henrietta Lacks’ stolen cells and in J. Marion Sim’s experiments on African-American slaves, where bodies of color are exploited to serve needs other than their own. It’s also explored as an issue in modern-day movies like Transfer, a 2010 German film in which an elderly white couple pays a service to download their minds into young, black African bodies in order to regain their youth and vitality.

In the face of a past and present which selectively devalues the lives of some at the expense of others, what’s the best way to make reproductive technology more equal?

Can technology help women of color imagine new ways to assert control over their survival, their bodies, and their reproductive freedom?

The United States is changing. It’s projected that white people in the country will become a minority in about 30 years. Fewer white Americans are being born than are dying, while more babies of color are U.S.-born. Over half of all children under the age of 5 in the States are people of color.

There are rumblings in the media that this trend (coupled with increasing numbers of interracial marriages and births) will signal the end of racism–as if merely combining or increasing numbers might solve the issue of white supremacy. The children may be our future, but I also believe that we are more than able to project our current hierarchical baggage onto them, especially if we fail to be thoughtful about the use of current and emerging technologies. The remaining effects of colonialism and historical oppression still affect people of color worldwide, especially through the use of supposedly neutral technology.

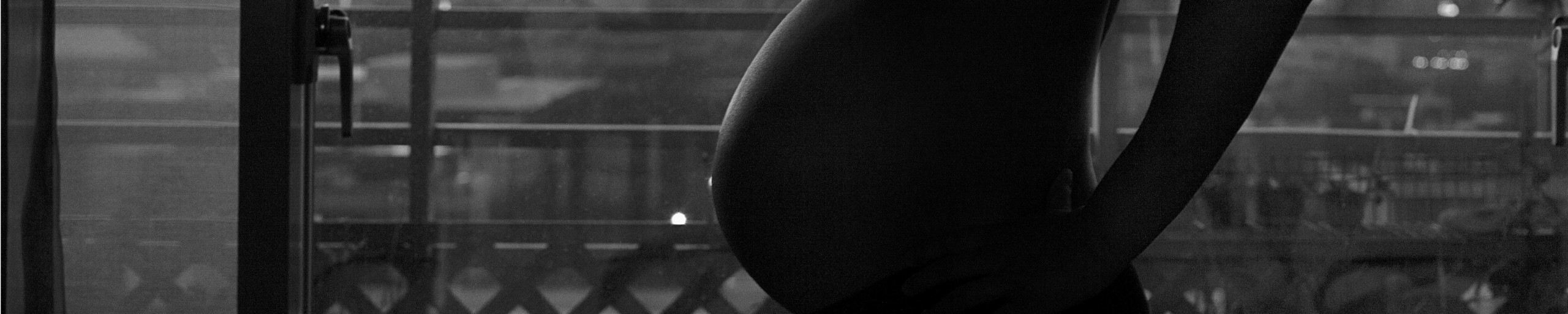

Despite current birth trends, there is certainly social pressure against the reproduction of babies of color, particularly for black women. The stereotype of the “welfare queen,” who has children only to receive state money, often gets applied here. Meanwhile, black women face the pressure of a statistically increased likelihood that their offspring will endure harm by the state; that is to say, black women are afraid to have children, lest they die at the hands of the local police or find themselves in the clutches of a flawed legal system.

These women are the producers of black bodies, but at every turn their desires to have children are attacked in a way unique to people who look like them. Babies of color, hailed as innocent and full of our purest hopes, will have a prominent place in our future–yet ensuring their existence and survival in the present seems difficult. We have work to do to guarantee that they inherit an equitable world.

Afrofuturism is one way for us to envision a less prejudiced use of both existing and emerging technologies. Ytasha Womack, author of Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy, explained the value of Afrofuturist art, literature, and music like this:

[Afrofuturism] inspire[s] people to take more agency in their lives, and actually think about the future–and in some cases, actually think about technology and feel comfortable being in that space “¦ [by] challenging norms, and actually embracing ideas that come to them.

Here are some examples of black women artists creating work this way right now, pushing the boundaries of control over technology and its relationship to their bodies:

1. The video for Missy Elliott’s “The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)” is often appraised as showing Elliott’s body in the way that she wants it to appear, as a black, plastic cyborg-like contortion that expands and moves in various strange, new ways. Writer Derica Shields spoke on a panel for Rhizome and the ICA about how to interpret it:

“But what I think is happening with the black women cyborg is that the invulnerability is not really geared towards immortality but rather towards survival and the ability to reproduce one’s self without becoming exhausted.”

2. Likewise, Wangechu Mutu’s art often features the cyborg black female body, urging us to imagine the marriage of woman and technology. When asked about her work in an interview with CNN, Mutu responded that it is a celebration of the body in the face of being despised. When pressed further, she said:

“Being taught to despise your body is being taught to perhaps admire someone else’s body more than yours–being taught that your body is good for certain things and not for others. It’s good for labor, but it’s not ideal if someone were to sit in a political post or something. It belongs in a certain frame and not in others and I think that was something taught to us, given to us or forced upon us.”

3. Musician FKA Twigs described her audio and video EP, M3LL155X, as “an aggressive statement conceptualizing the process of feeling pregnant with pain, birthing creativity, and liberation.”

In the videos for the EP, she dances while heavily pregnant and subsequently gives birth to a series of scarfs and colored paints. The videos are transgressively framed as a woman completely in control of her body and her work.

In another video reimagining her music in an advertisement for Google Glass, she calls up dance moves on her headset–summoning into the frame troupes of futuristic-looking, self-stylized dancers with whom she observes, learns, and collaborates. She manages to turn something that’s meant to be an ad into a public and visceral grappling with the relationship between new technology and the body.

In a talk during Art Basel Miami Beach, FKA Twigs explained that she did the advertisement because Google gave her complete control over its direction. She spoke about how the video was a play on how people see her, as a sort of alien or a cyborg:

“So even me, without speaking, just making all these goofy words [does alien-like clicking voice from the commercial]–I know that’s how people want me to be. It’s not true. I’m not like that. I’m just a human, but I could just tell that that’s how people want me to be.”

Here, through an Afrofuturist aesthetic, we see black women creating their own realities, both as a reaction to societal forces and as an inspiration for better uses of technology. What they create centers themselves and their desires, challenging the status quo. They have control over their bodies and technology, conceptualizing and modeling the equitable ways that technology can be used in the present and future.

When talking to me about Radiolab‘s “Birthstory” episode, Professor Thompson said, “[We’re currently] so far from the world that a reproductive-justice orientation would have to be in place to even begin to talk about these technologies being places that undermine (rather than make worse) racism, classism, sexism, and transnational hierarchies.”

But there is hope that Afrofuturism can help to usher in that world, by getting young, increasingly diverse groups interested and involved in technological advances, said Michael Bennett, an associate research professor at Arizona State University’s School for the Future of Innovation in Society. “It’s a mode of thinking and a way to make some of the most vital pop culture [and] policymaking that I think is sorely needed across the board–but particularly in black communities,” he explained.

For her part, Womack sees the internet as the great distributor of these ideas, helping to join people of like minds to think together in new ways. Meanwhile, Thompson spoke of “taking some of these technologies back into the hands of communities,” perhaps through inspiring people to take up biohacking, or do-it-yourself citizen science to use technologies as they imagine them.

There is an answer to the question of who will shape the uses of present and future technology. It will be the alien dreamers who are inspired to become doers.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our collection of conversations about Afrofuturism, curated and edited by Florence Okoye of Afrofutures UK. Click the logo to read more.