Read the previous installment: “The Future We Were Promised“

While doing the research for “A Visual History of the Future,” we collected a huge amount of incredible material. Most of it didn’t make it into the final series–but we still wanted to share some of these images. We’ve got extras from each installment, plus a bonus look at the future from Soviet and Japanese artists (more of which can be seen here).

If you haven’t read “A Visual History of the Future,” these images offer a taste of the areas it covers. The main series page gives an overview of each episode, or if you want to time-travel back to the beginning, head to our first episode. And if you want to see even more of our research images, nearly 900 of them are collected on the series Pinterest board.

The Beginning of the Future

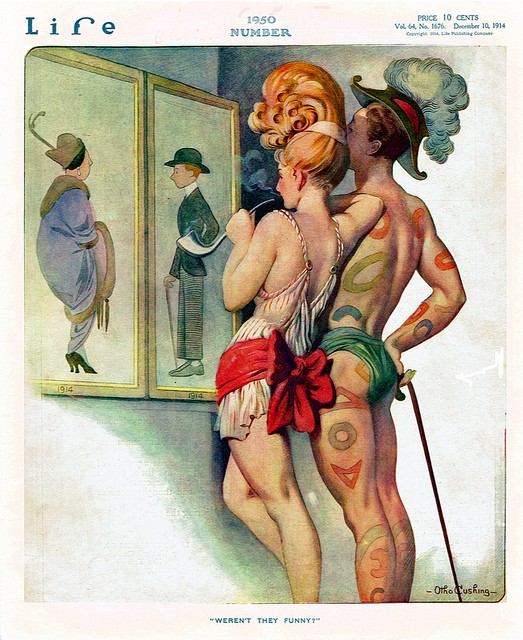

Most futurist images were concerned with technology, but Otho Cushing‘s satirical cover for Life envisages the (skimpy) fashions of the future. With colorful tattoos and ladies smoking pipes, he insightfully anticipates both women’s emancipation and the rise of the hipster.

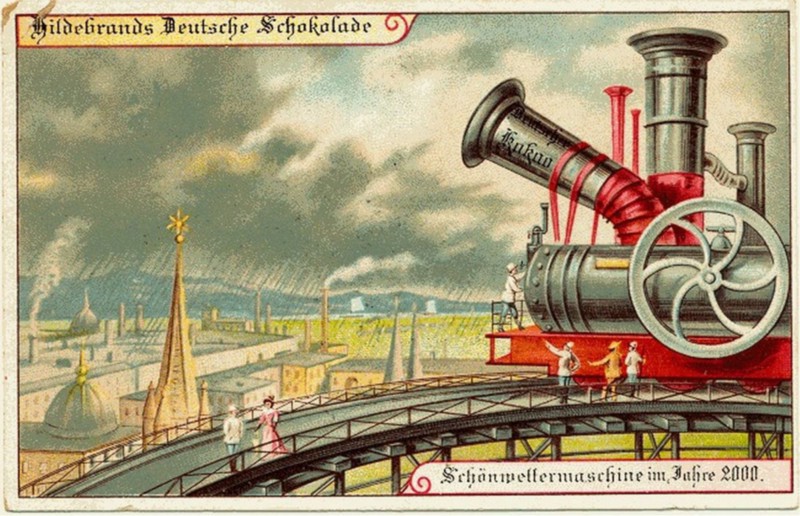

Toy companies and cigarette manufacturers promoted products using images of the future, so the German chocolate company Hildebrands followed in that grand tradition with their weather-controlling machine.

An extremely early–and theatrical–take on home entertainment: “Compliments of Maher & Grosh Cutlery Co.”

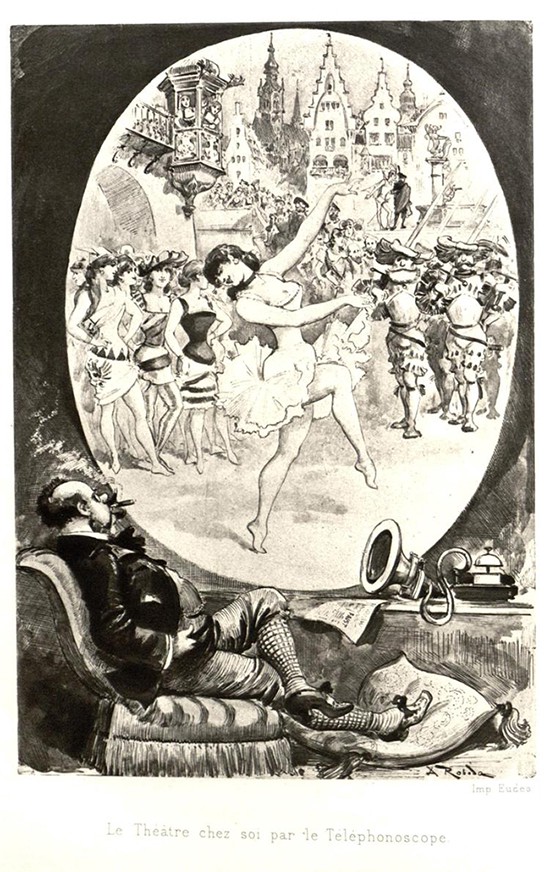

Albert Robida may have been the first to visualize the concept of television–and the future of entertainment for the discerning gentleman–in this image from 1869.

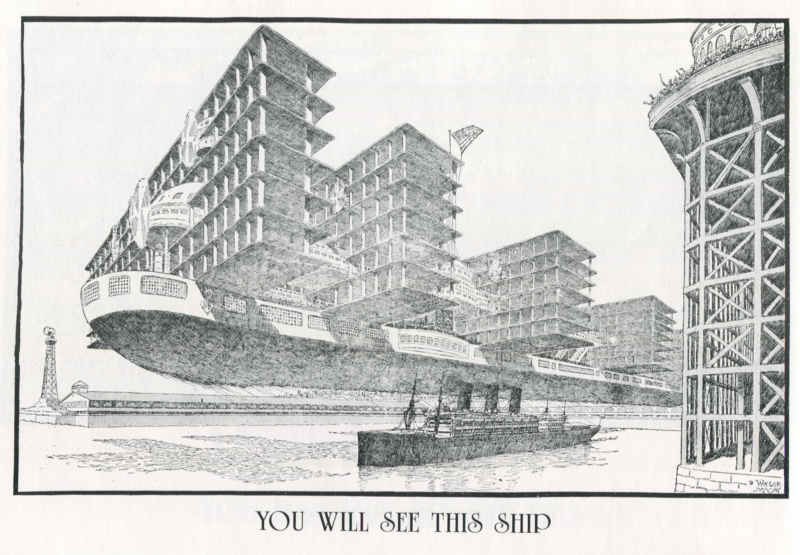

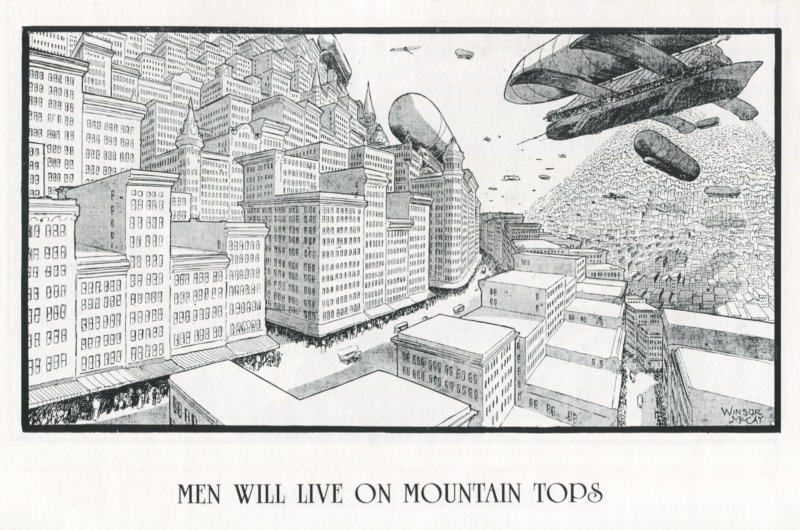

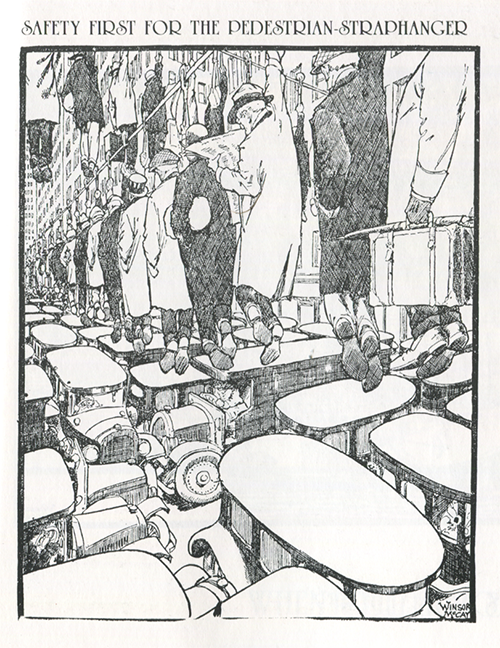

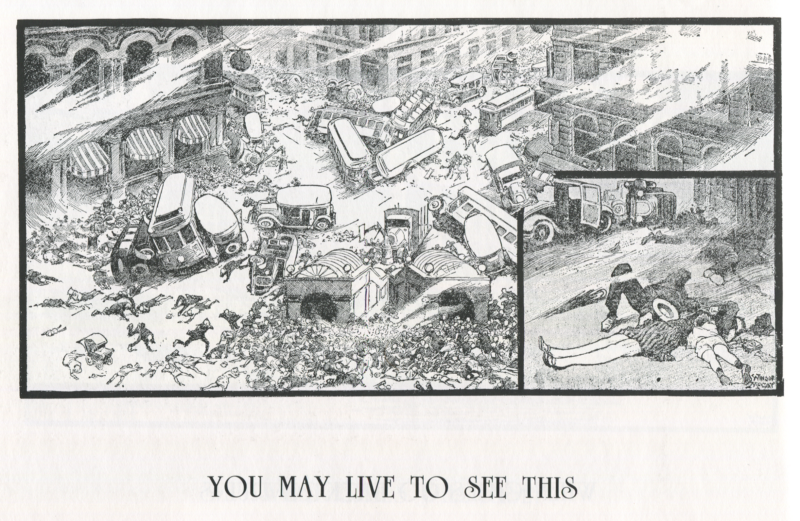

Winsor McCay created the groundbreaking comic strip “Little Nemo” and pioneered hand-drawn animation in “Gertie the Dinosaur.” He also lent his considerable talents to depicting the future. Below are images from an editorial strip he produced during the 1920s titled “Sermons on Paper.”

A flying aircraft with wings galore dwarfs the cruise ship below.

McKay’s eye for scale–and exaggeration–is on display in this image of future cities.

His tongue is often firmly in his cheek, employing his unique humor to produce this wonderful traffic-jam-beating method.

Finally, a more disturbing look at a less hopeful future, echoing imagery of a nuclear blast or other catastrophic incident.

How Ad Men Invented The Future

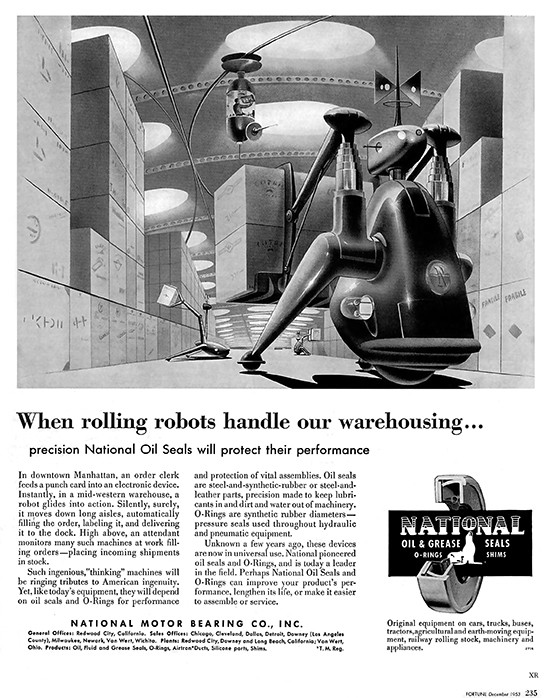

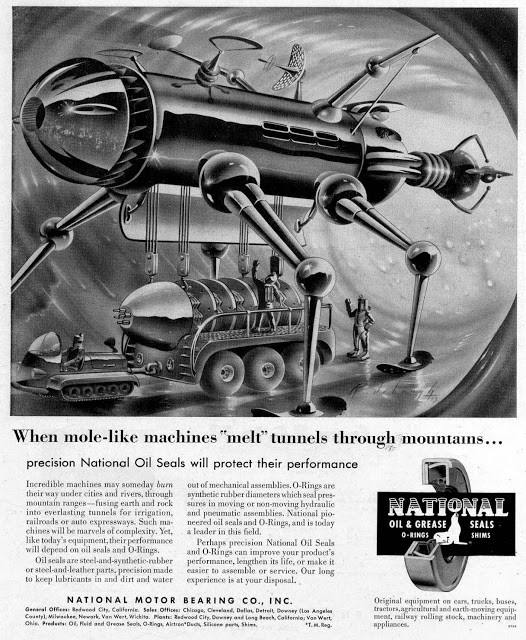

As well as illustrating ads for Bohn, Arthur Radebaugh produced a series of images for the National Motor Bearing Co. that focused on the industrial and manufacturing future–with some stylish and industrious robots.

Radebaugh’s tunneling machine predates the atomic machine shown in “Magic Highway U.S.A.” by five years.

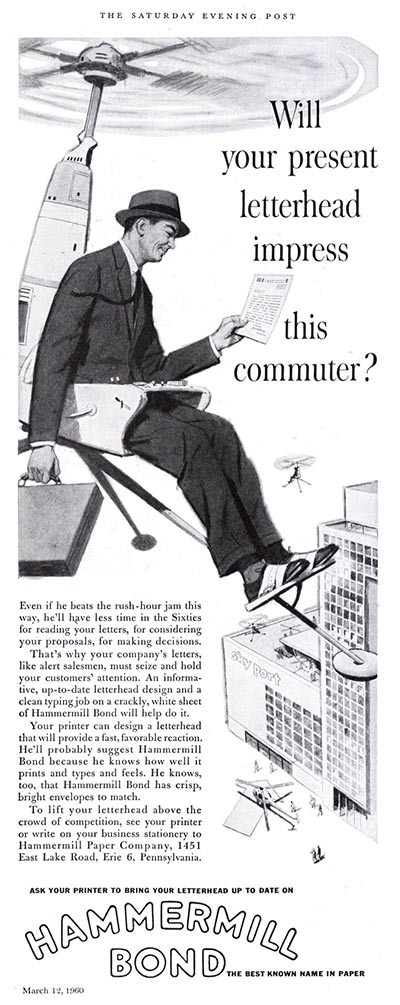

When it came to advertising, it wasn’t just the obvious heavy industrial manufacturers that wanted a slice of the future; groups like the paper industry wanted in, too. When flying to work in your personal helicopter is a daily event, you’re going to need a pretty incredible letterhead on great paper to impress the average commuter.

Fact, Fiction, and the Future

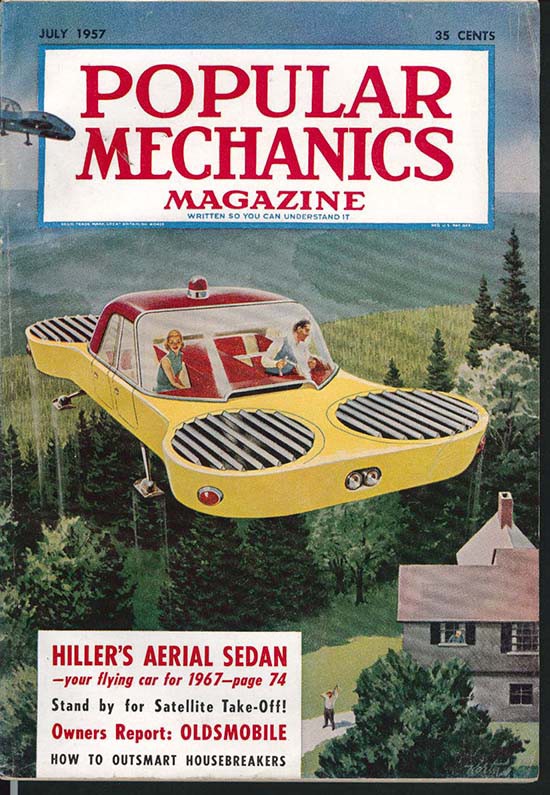

Flying cars were never far from the mind of the average futurist. When this sedan made the cover of Popular Mechanics, it was only a decade away.

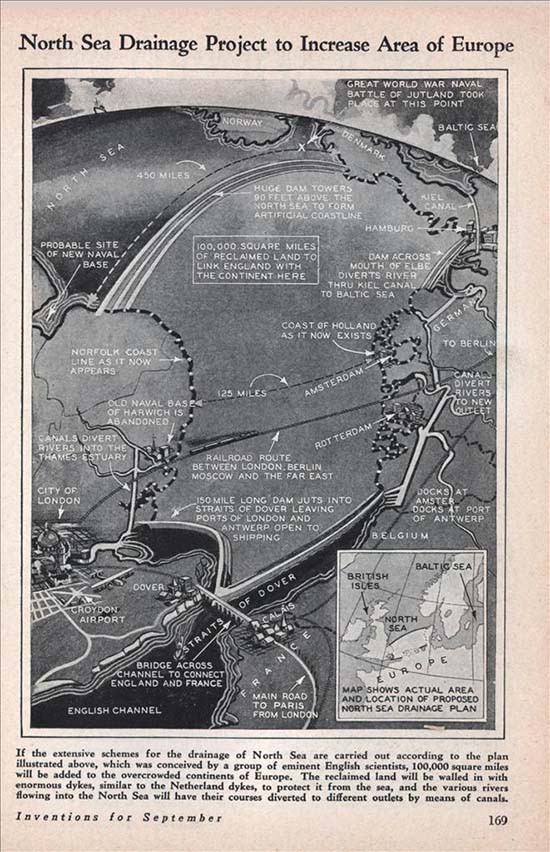

Big engineering projects don’t come much bigger than this: draining the North Sea to reclaim submerged land.

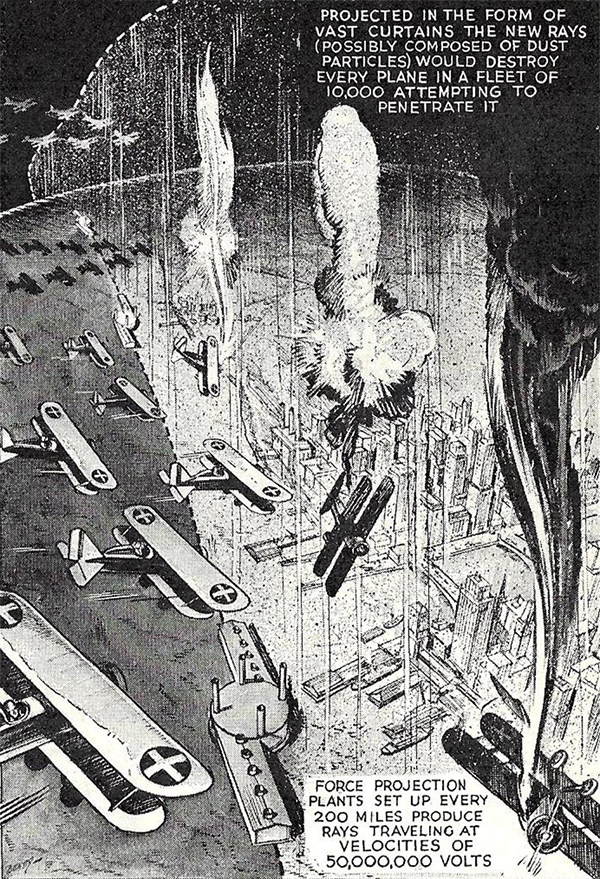

Engineering projects also work for war and defence. Nikola Tesla’s idea for a “death ray,” or, more appropriately, a death wall, is covered in this 1934 issue of Popular Mechanics.

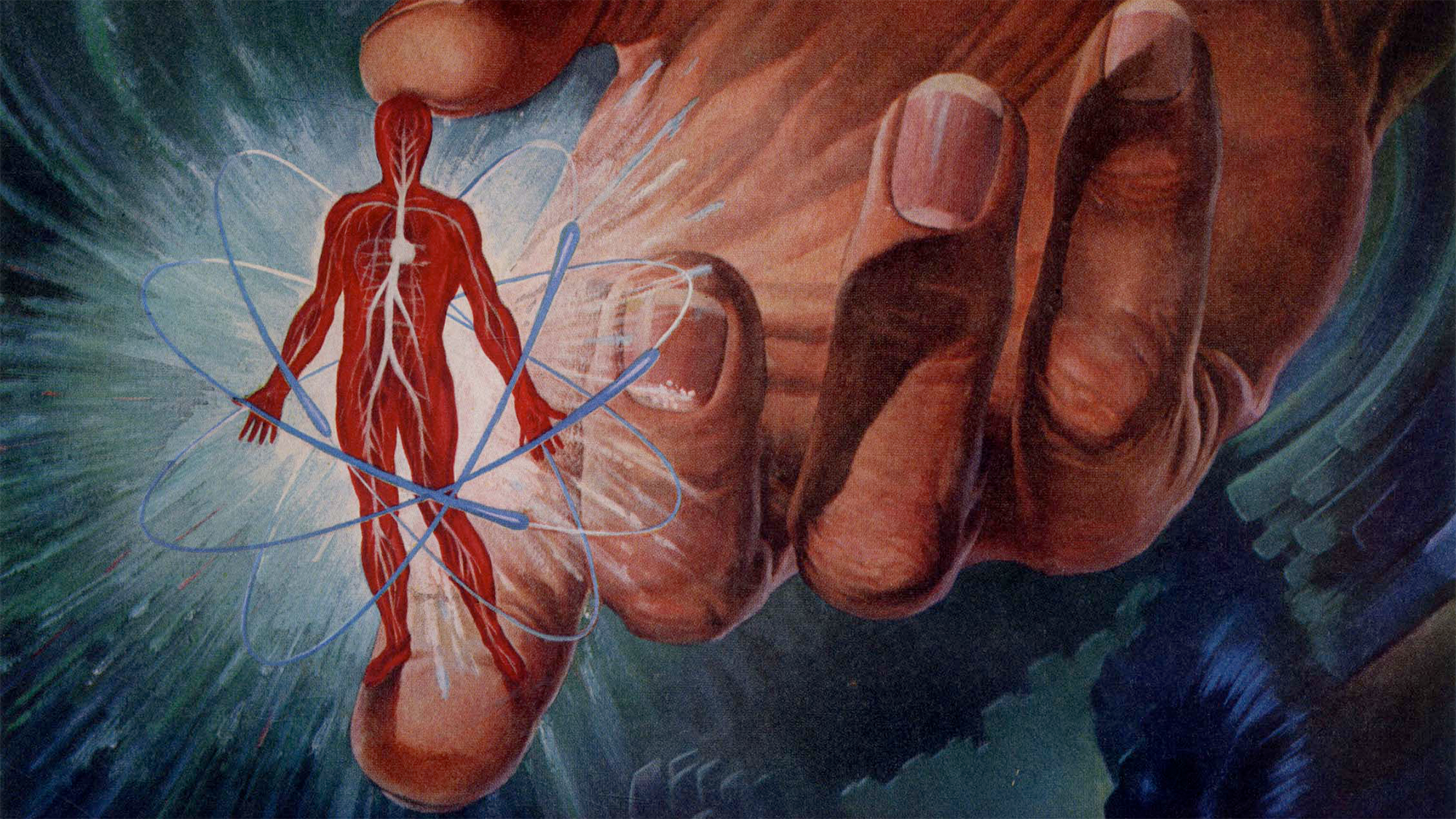

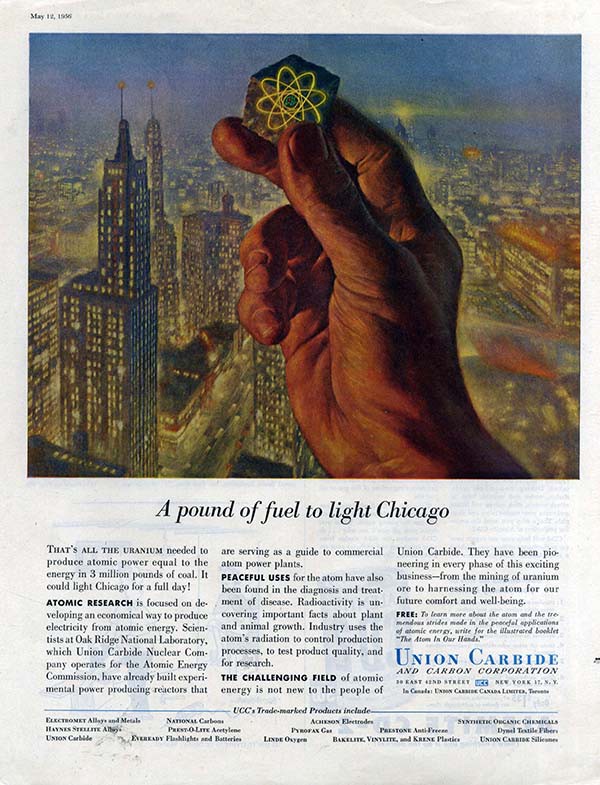

The positive power of the atom is sold to the public in this 1956 advertisement from Union Carbide.

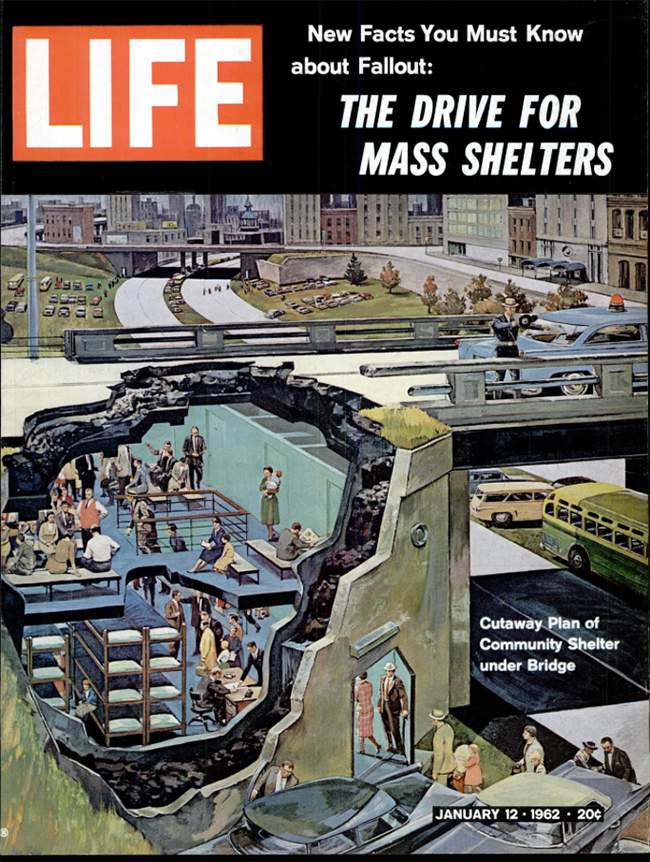

And the destructive flipside of the atom is covered in this 1962 issue of Life.

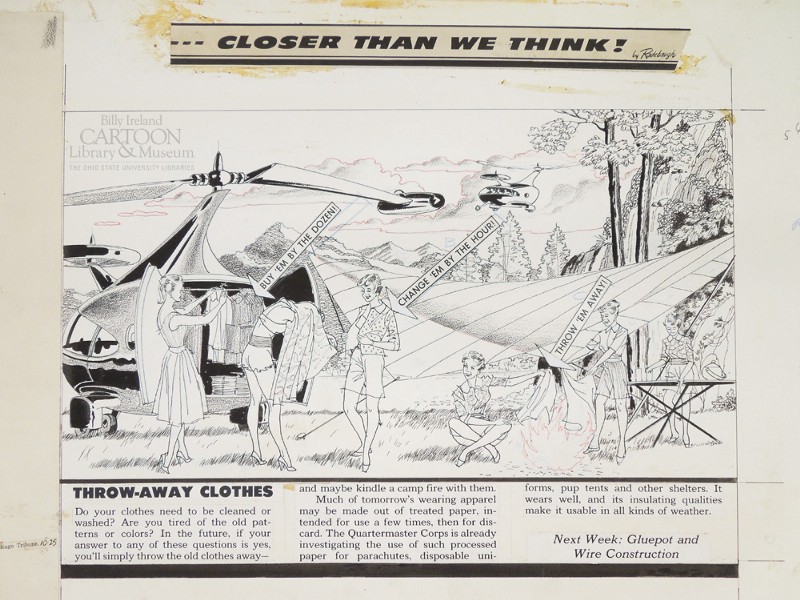

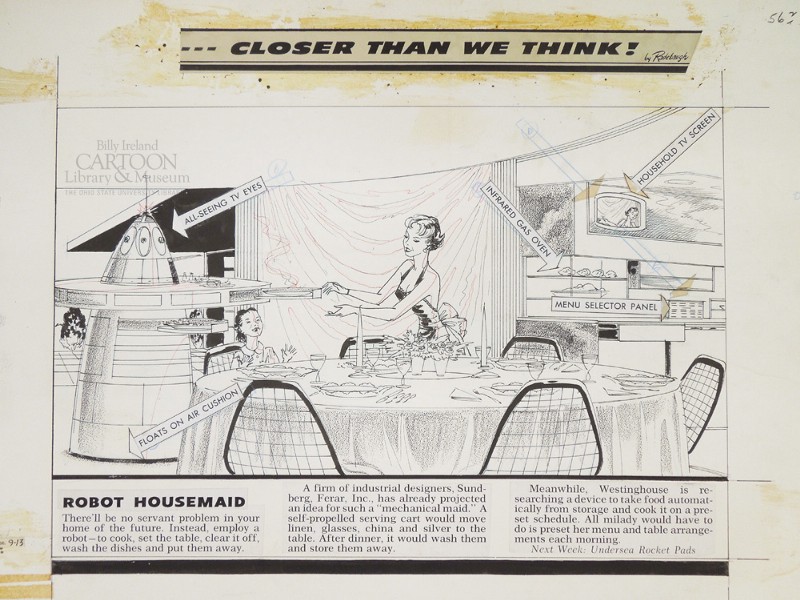

Arthur Radebaugh and his “Closer Than We Think” series featured heavily throughout our series, and the following pair of images are some of his original artwork, courtesy of the Ohio State University Library. Radebaugh’s life and work is covered in detail in this excellent documentary from Clindar Films, if you have the opportunity to watch it.

We’ve also discussed Syd Mead’s influence on futuristic design, but this image of a “the four-legged, gyro-balanced, walking cargo vehicle” in particular stood out as”¦ familiar.

Joe Johnston, the art director on The Empire Strikes Back, confirmed that these advertisements influenced the design of the film’s AT-AT walkers.

Animating the Future

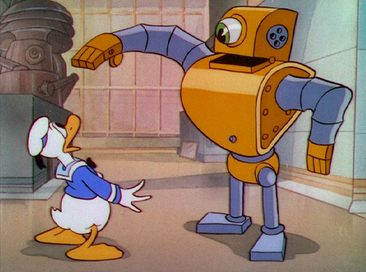

Donald Duck didn’t make it into “Animating the Future.” But in a 1930s Disney short, “Modern Inventions,” he visits a “Museum of Modern Marvels” where he meets this robot butler.

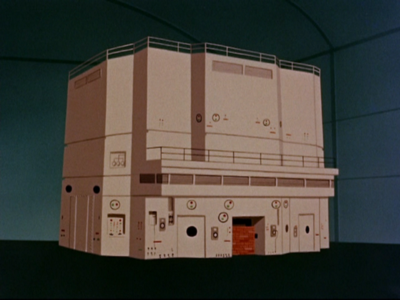

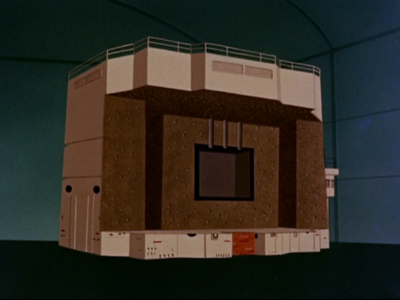

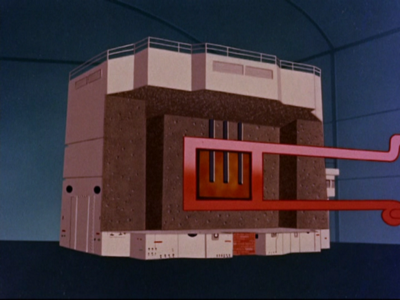

This sequence from “Our Friend the Atom” frames atomic power positively, showing how an atomic reactor works.

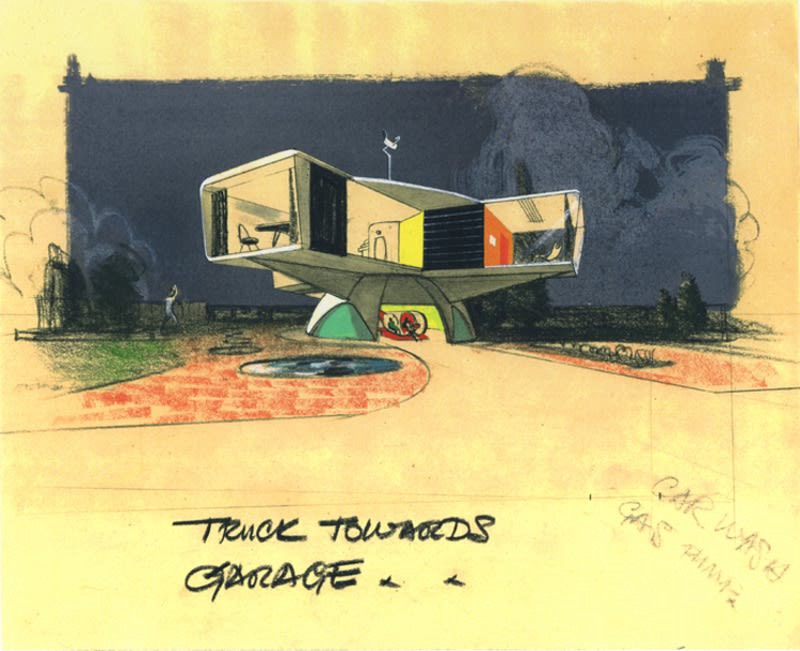

This storyboard image from “Magic Highway U.S.A.” features a sequence about the Monsanto House of the Future, an attraction at Disneyland’s Tomorrowland in 1957.

Architects of the Future

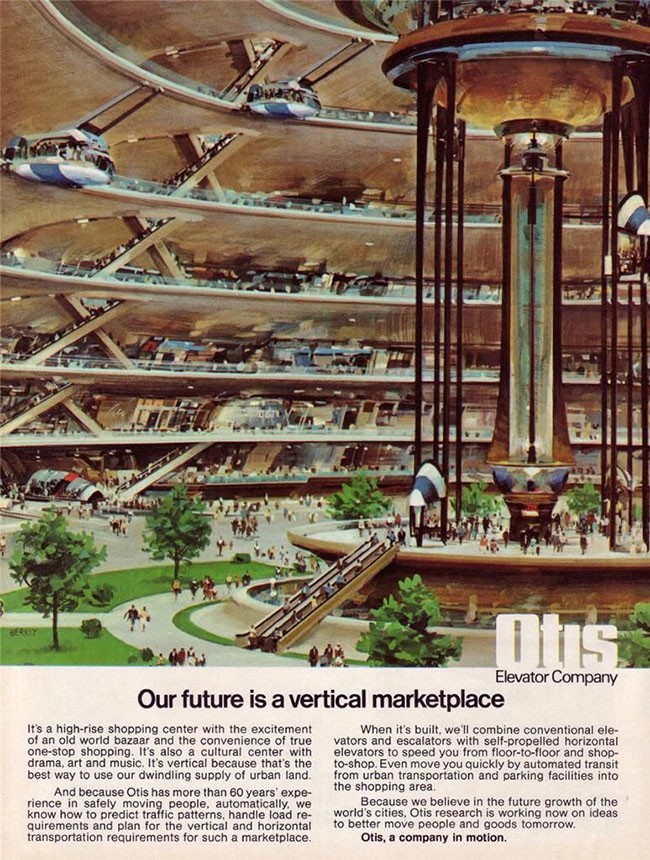

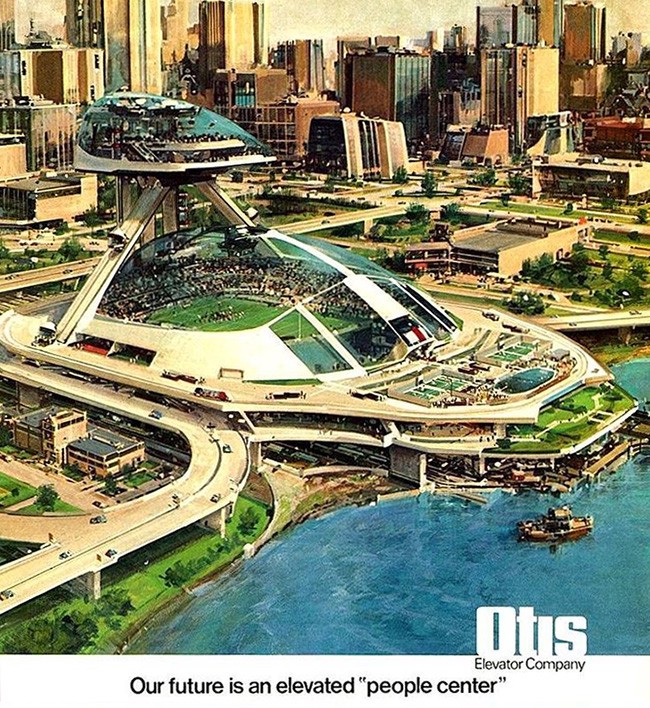

In the 1970s, the Otis Elevator Company produced a series of advertisements that showcased illustrator John Berkey’s highly detailed, intricate, and futuristic city designs.

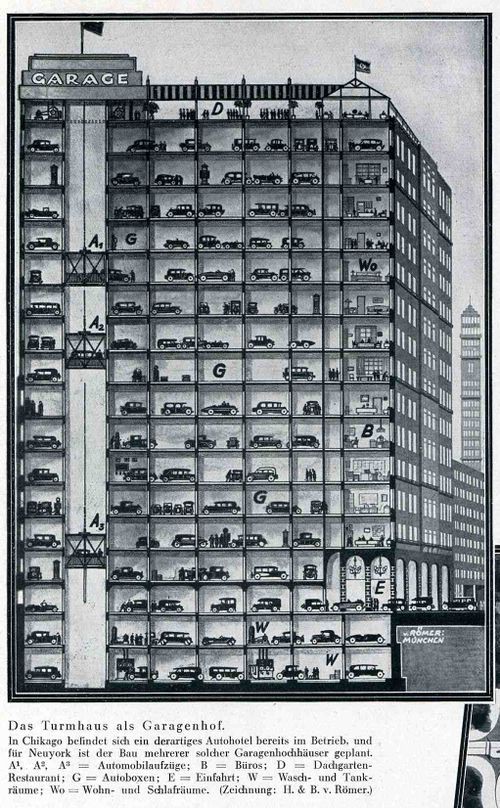

In 1930, an idea for a multistory skyscraper shows how the car was beginning to dominate how future cities would be shaped.

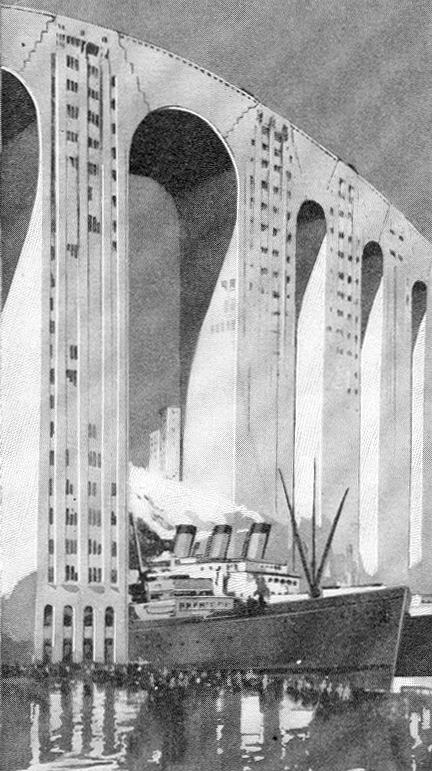

An idea reminiscent of Hugh Ferris’s skyscrapers on a bridge, except this time the skyscapers are the bridge.

Beyond Western Futures

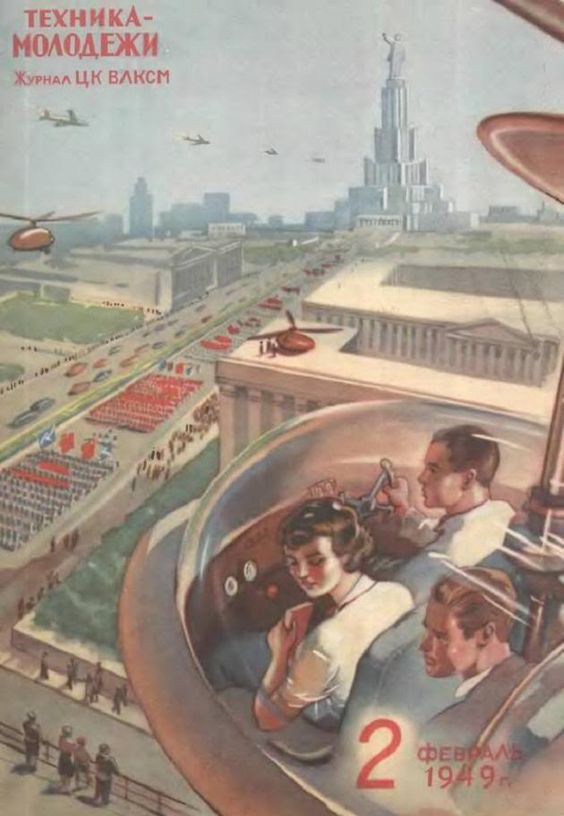

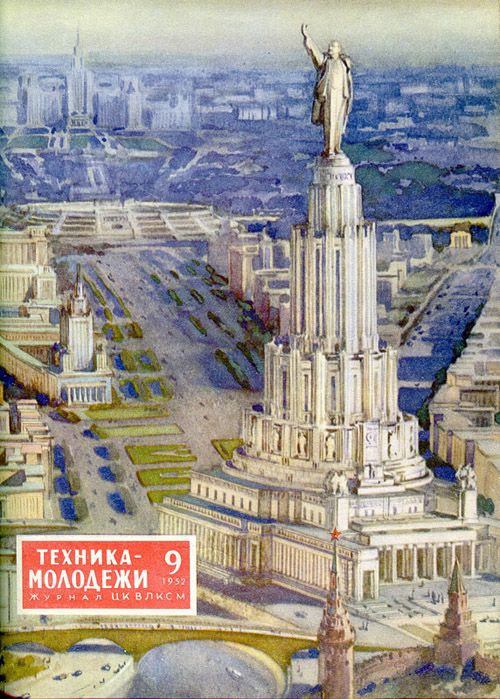

Of course, the United States wasn’t the only country with its eye on the future. The U.S.S.R.’s equivalent of Popular Mechanics, Technology for Youth, had spectacular covers and ideas. Flying cars were a global preoccupation.

The iconic structure on this cover is the planned-yet-never-built Palace of the Soviets, which would have been the largest structure in the world at the time.

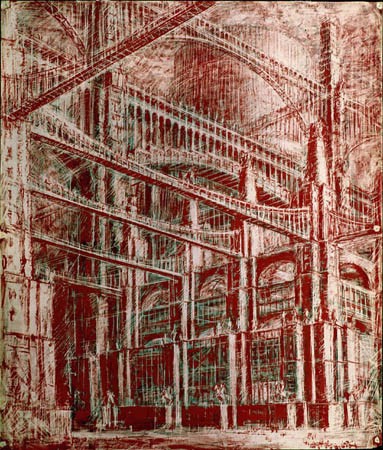

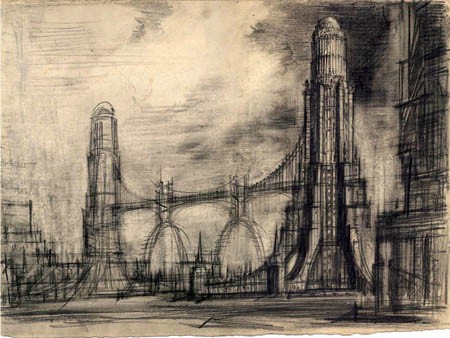

The U.S.S.R. even had his own Hugh Ferris, Yakov Chernikhov, who mixed gothic sensibilities with grand futurist vision.

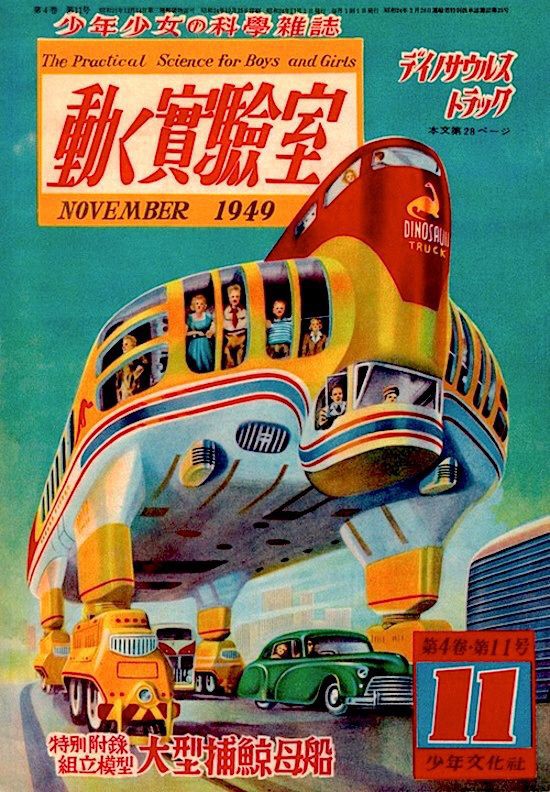

And finally, this magazine cover from Japan looked familiar, and then I remembered the Chinese Transit Elevated Bus concept that generated excitement a few years ago. It’s never moved beyond the theoretical–maybe we’ll see it again in another 70 years?

Read the previous installment: “The Future We Were Promised“

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. A Visual History of the Future is a five-part series on the way artists’ visions of the future shaped the world we now know.