Innovation can come from the unlikeliest of places. For Sharon Terry, it was the shocking discovery that her children suffered from a rare genetic disorder that led her on a life-changing journey. Her research about the disease uncovered a lack of communication between medical research teams, prompting her to invent new ways for medical researchers and patients to collaborate to find a cure.

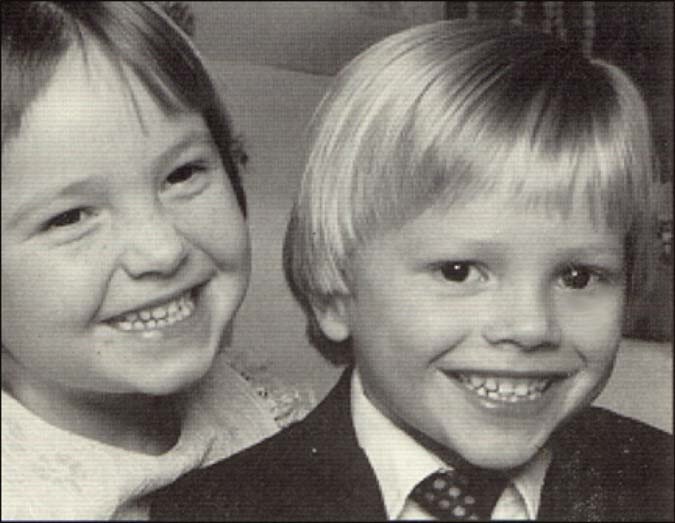

She’ll never forget the moment that changed her life. “I was at my niece’s first birthday party in 1992, the first happy event since the death of my brother about four months before, and I noticed in the softening sunlight three small dots on each side of my daughter’s neck,” she recalled.

Over the proceeding months and years, Sharon periodically asked their pediatrician about the dots, why they were only on the sides of the neck, and why they were slowly increasing in number over time. More crucially, she wanted to know if they were threatening, and whether she should be concerned.

Sharon was told that she was worrying needlessly, but she was never really satisfied. She eventually made an appointment to see a dermatologist. That’s when her world started crashing down. “She has pseudoxanthoma elasticum, PXE,” the dermatologist told her.

“I could not absorb the words he was speaking. Something about this being systemic, and an autosomal recessive disease, and not much being known about it. I just saw my gorgeous children, and heard him speak about wrinkly sagging skin and blindness.”

Never having heard about PXE before, Sharon went to two medical school libraries and photocopied every article on PXE that she could find. “I brought home 400 articles, and couldn’t understand any of them,” she said. “Only that there were grotesque photos of sagging skin, and descriptions of early blindness, and premature death.”

Despite initially feeling it wasn’t their place to do so, Sharon and her husband began questioning the papers and journals they were reading. There seemed to be hundreds of different perspectives, yet most focused on single cases of the disease. The couple was also troubled that none of the papers reported failed experiments. Surely they couldn’t have all been successful?

“Another pattern that emerged was a lack of collaboration. In the few cases where an author wrote multiple papers, it seemed that those papers were with the same group of authors. There was no crossover, or cross-fertilization,” said Sharon. This became poignantly clear as researcher after researcher contacted her asking to draw blood from the children.

Amazingly, none of those practitioners were sharing their samples. It became apparent that in a race to find the gene, researchers were not only failing to collaborate, but they were proactively blocking each other’s progress. For Sharon, as she contemplated how this reduced the chances of a cure for her children, this was nothing short of extraordinary.

After initial hesitancy, Sharon and her husband came to the conclusion that the system simply had to change, and they reluctantly set out to change it. They founded PXE International in early 1995, an international foundation dedicated to the research of PXE. They started directly funding research–on the condition that the research was open and collaborative–and made their first grant of $10,000 to the Jackson Laboratories in Bar Harbor, Maine, to look for PXE eye signs in mice.

The lack of wider collaboration still troubled them. Then, out of nowhere, the answer came. “All we had to do was amass the blood, tissue, and clinical information from PXE sufferers in an orderly way, and then the researchers would need to come to us. We could then set the rules–to eat you must “‘play well with others.’ “

And so, the PXE International Registry and BioBank was born. “This was, as far as we know, the first lay-owned blood bank,” said Sharon. By the middle of 1995 they were collecting blood and tissue from affected individuals all over the world–through medical conferences, newspaper ads, and outreach to specialists.

These expanded resources, combined with months of late nights, resulted in their discovery of the gene. A major breakthrough. Sharon co-authored the gene discovery paper with not one, but two labs, in a back-to-back publication in Nature Genetics.

“I then participated in patenting the gene, as a co-discoverer, and all of the patent holders turned all rights over to PXE International. At that time, I was the only layperson to patent a gene–that may still be the case. I consider myself a steward of the gene, shepherding it through to creating diagnostic tests and trial therapies,” said Sharon, proudly.

Over the following years the work continued and grew, and Sharon became president of the board and then CEO of Genetic Alliance, which was renamed from the early, more narrowly focused Alliance for Genetic Support Groups. In her role, Sharon led the coalition that promoted GINA–the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008–a law that Senator Edward Kennedy proclaimed from the floor of the U.S. Senate as the “first civil rights law of the new century.” He thanked Sharon by name.

Genetic Alliance later established the nation’s newborn-screening clearinghouse, grown from four to a staff of more than 20, and was named Washington, D.C.’s Best Place to Work in 2010. In 2013, Genetic Alliance won $400,000 in first prizes in three innovation competitions. It has been nothing short of an amazing journey, sparked by that shock diagnosis over a decade ago.

So, where are things now?

According to Sharon, these days her greatest challenge is the same as it has always been, but in other ways always new. “It is myself. I must release myself to be big, to be sure, to be humble, to be one with others, to be free, to belong, to give freely and to not hold back. I am thrilled to be on this journey and grateful beyond words for my companions on the path. Life is far too short to do anything but go for it.”

And though she was reluctant to begin, and certainly at various points along the way, she knows that all of this has been a great gift in her life, and for the world.

This is an edited version of “Without Mud There Is No Lotus,” which first appeared in The Rise of the Reluctant Innovator, a book on social innovation edited by Ken Banks and published in 2013.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Histories of”¦ section, which looks at stories of innovation from the past. Click the logo to read more.