Read the previous installment: “Fix What‘s Broken“

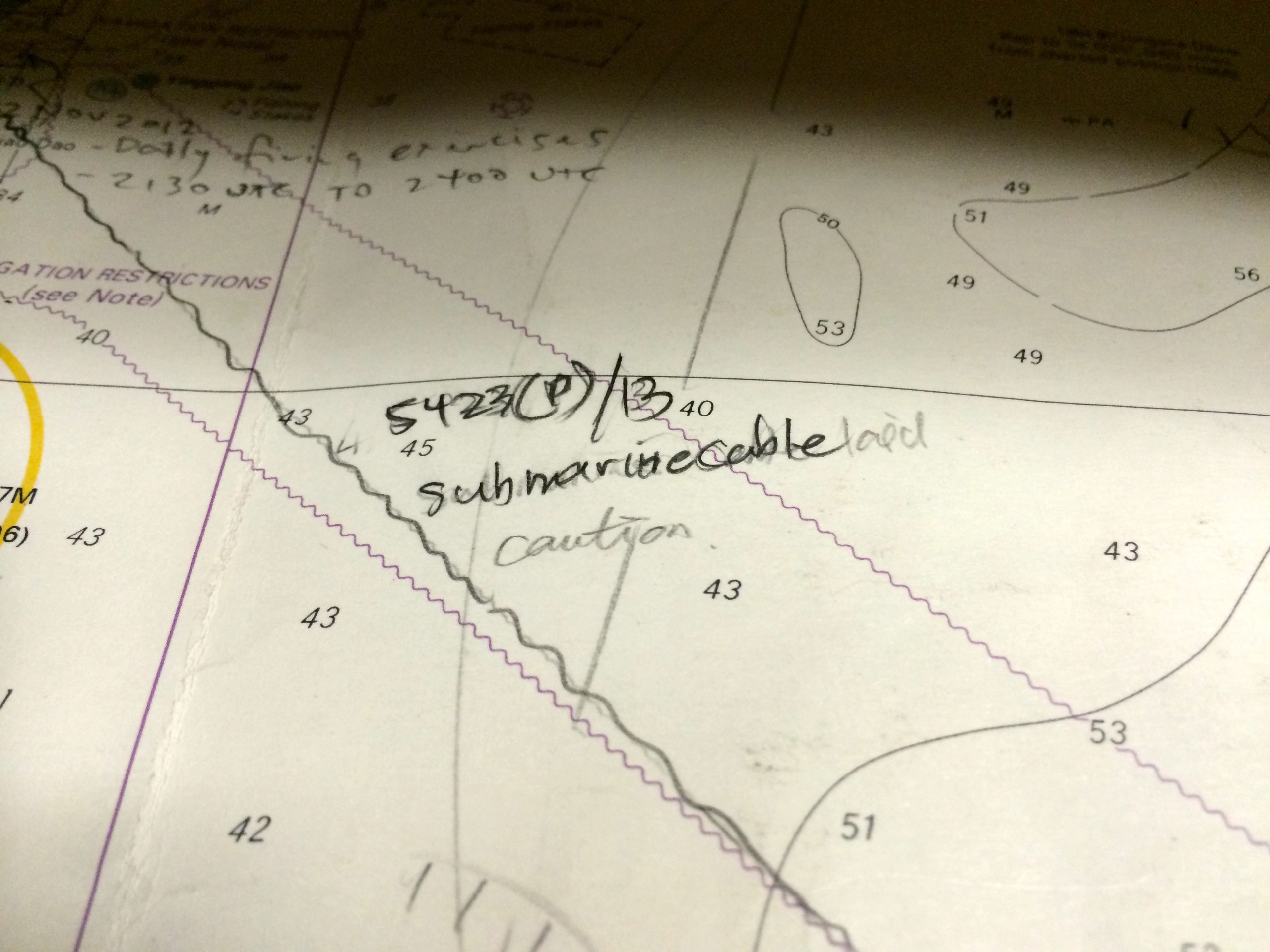

Examining the route plotted in pencil on the bridge’s paper charts, I see we’re about to sail across an exciting piece of maritime infrastructure. I lean over the bridge wings and look out for it, but there is nothing visible–the blue sea here is no different than it was a few nautical miles ago.

Some 300 feet below the water’s surface a submarine cable lays on the seabed: an Internet backbone connecting nations. A bundle of fiber optics only a tenth of an inch wide, it’s wrapped in shielding and insulation and stretches for thousands of miles along the ocean’s floor. It’s invisible to us aboard the vessel, appearing only as a warning on a chart.

Overlay a map of submarine cable routes atop a map of popular shipping routes and you’ll see little difference. These cables visit the same cities our ship does, landing at Busan, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore; and they follow the shortest possible straight line between them. The cables carry 90 percent of international data while the ships carry 90 percent of world trade.

Occasionally, the cables break. Sometimes it’s from natural causes, such as a shark bite. Or from the movement of the seabed in earthquakes. The Hengchun earthquake in 2006 resulted in 18 cuts in eight different cable systems, while the 2011 TÅhoku earthquake damaged half the cables crossing the Pacific.

Other cable breaks are the fault of human actions. A ship dragging anchor can easily sever a submarine cable, cutting off the international flow of information. There’s a tension between the cables and ships traveling the same paths. Near land the cables are buried in the seabed for protection, but farther out at sea they lay exposed on the seabed.

This is why the charts document the cable paths. The charted paths are not precise, lest they help someone deliberately find the cables. In 2007 a repair ship tending to a break in the SEA-ME-WE 3 link off the coast of Vietnam found nearly seven miles of submarine cable missing, stolen for its scrap value.

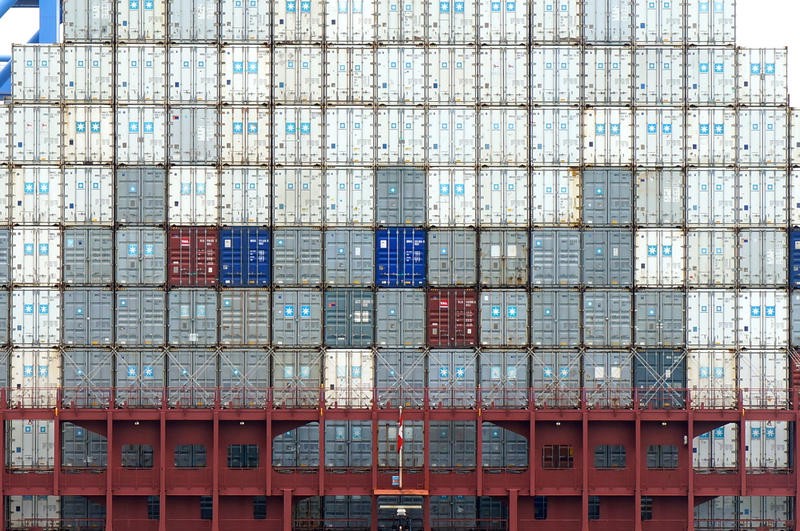

I wonder what the scrap value of the thousands of metal shipping containers aboard the ship is. Much like the cable below, I have no idea what is being carried inside them. Neither does the crew. The entire ship is designed around these boxes, to transport them from one routing point in the network to the next.

For each container the ship knows only its metadata. We know where it sits aboard the vessel, how much it is supposed to weigh, and at which port we are to discharge it. There’s no need to know any more. We don’t know its contents, final destination, or point of origin.

The only time the crew sees the inside of a container is when there’s an accident. Sometimes, despite their sturdy builds and container certification schemes, containers will break after years spent in harsh environments at sea. One crew member recalls clearing piles of clothing blown across the deck following one breakage–as well as the weeks following when everyone aboard was wearing the same brand of clothing.

Another time, a crew member recalls, an official in one port casually referred to their vessel as “the drug ship.” When asked, the official clarified that after their ship’s previous visit a forklift had accidentally torn open the side of one discharged container, revealing bales of marijuana. The crew had no idea it had been transporting cannabis, and this crew member in turn never would have known were it not for an accident and this chance conversation.

Like the cables below, the ship is just a conduit in a network, passively carrying packets to the next node. Largely unnoticed, save for disruptions at the hand of accidents, failures, or disasters, it sails on, carrying cargo to its next destination in the chain.

Read the previous installment: “Fix What‘s Broken“

Please note that this work is not available for republication under the terms of a Creative Commons license, as per most of our other content.

Postcards From A Supply Chain follows Dan Williams as he traces consumer goods back through the global shipping system to their source. It was organized by the Unknown Fields Division, a group of architects, academics, and designers at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London.