In the dusty scrubland just outside of Albuquerque, N.M., fog is a rare occurrence. The residents of the city usually wake up to bright blue skies. But in many parts of the world fog is a constant presence, rendering security cameras, optical sensors, and other equipment useless whenever it rolls in. For the world’s military forces, it can be the difference between life and death.

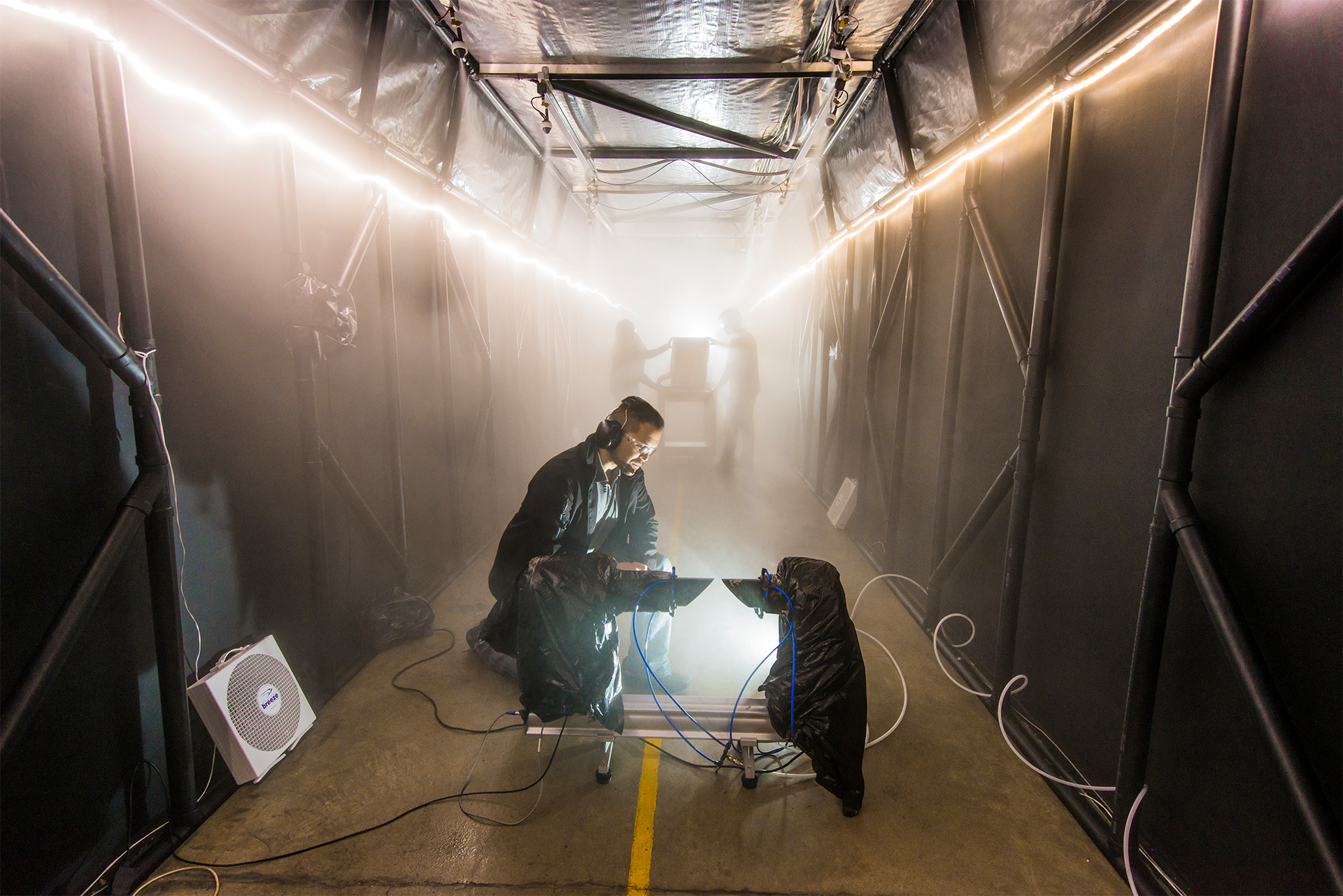

That’s why Sandia National Laboratories has built one of the world’s largest fog chambers at 180 feet long, 10 feet tall, and 11 feet wide. “The ultimate goal of this whole endeavor is to defeat fog,” said Rich Contreras, a systems engineer at Sandia. “From physical security and force-protection aspects, as scientists and engineers who care about national security, we want to be able to make it so that a security-force person at a site has the ability to maintain uninterrupted situational awareness.”

As expected, the cloud microphysics technology behind the walls of Sandia’s fog chamber is rather more advanced than the smoke machines you might see at a music festival. Fog droplets are layers of water condensed around some sort of seed particle–Sandia currently uses salt to simulate the fog found in coastal areas, but pollen, dust, or ice can also form fog depending on what’s available in the environment, the droplet size distribution and chemical composition changing accordingly. By measuring those variables anywhere in the world, Sandia can approximate its local fog.

“People need to see through fog,” said optical scientist Gabe Birch. “So much of the U.S. population is on the coastlines in places where fog exists. If you could discover an inexpensive technique to see better through it, there are a lot of people in [certain] industries who would be interested in that.”

The pea-souper created by Sandia’s machines is kept in place using air curtains and rubber baffles, and the walls are painted with black paint to reduce reflections and improve data quality. That makes the fog chamber far superior for trying to test devices than the real thing. “Fog is difficult to work with because it rarely shows up when needed, it never seems to stay around long enough once you’re ready to test, and its density can vary during testing,” said Contreras.

It looks terrifying, if the video below is anything to go by. Once the chamber is filled with fog, it’s not long before other people fade into faint shadows and then disappear entirely.

As well as testing security cameras and military sensors, it’s hoped that the fog chamber could be used to improve medical imaging technology. Birch explained that technology sees a very similar problem: “The physics in scattering events are the same,” he said. “It enables a lot of very interesting testing, because you can finally characterize your system’s performance by knowing the scattering that’s happening in the environment.”

It seems unlikely that Sandia will open its fog chamber to the public any time soon. But if it does, or if you can convince someone there to show you around, you can bet it’ll be one experience not to be mist.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Nature & Climate section, which looks at how human activity is changing the planet–for better or worse. Click the logo to read more.