Lyrics are arguably the one element left in music that is unmistakeably human. Great tomes of theory have been written about how to make memorable lyrics that resonate with people emotionally–but there’s no foolproof, conclusive route to success. What happens when you let a robot have a go at it?

We decided to find out by recruiting Finnish coder Eric Malmi–and an algorithm he created called DeepBeat–to write a couple hip-hop tracks. Man and machine, together in harmony. Or, that was the theory at least. Then, we found some rappers to actually perform them.

To get an idea of how important technology has been to music, let’s rewind to the 1970s, which saw the two greatest advancements in modern music. (No, not the births of Fred Durst and Fergie from the Black Eyed Peas.) These two events, which would go on to change music forever, were both technological in origin.

The first was the widespread adoption of the synthesizer, which expanded man’s musical palette from one that was limited (could you hit it, bow it, or pluck it) to one that is theoretically unlimited. The second was the birth of hip-hop, with its cut-and-paste sampling culture and the idea that preexisting material could be repurposed to create something new, fresh, and different.

The 1980s offered further changes, as analog synths morphed into computer-controlled ones and sampling moved from turntables to digital. Before long, there was the birth of dance music, which took these technologies to their zenith–the computer now ruled everything, creating all the sounds, dealing with all the samples, and even correcting the one remaining “human” element (the voice) via the use of autotune and correction software like Melodyne.

So dominant is the computer in modern music that people have begun to think about whether it could write a song all by itself. After all, researchers from Bristol University created a formula in 2011 (which later became an app, The Hit Equation) that boasts 60 percent accuracy in predicting whether a song will be a hit by using musical characteristics such as time signature, “danceability,” tempo, harmonic simplicity, and loudness, all correlated against the prevalent, popular musical styles of the time. If a computer can predict which song will become this summer’s best jam, could it not write the song itself?

Step forward, our new friend, DeepBeat.

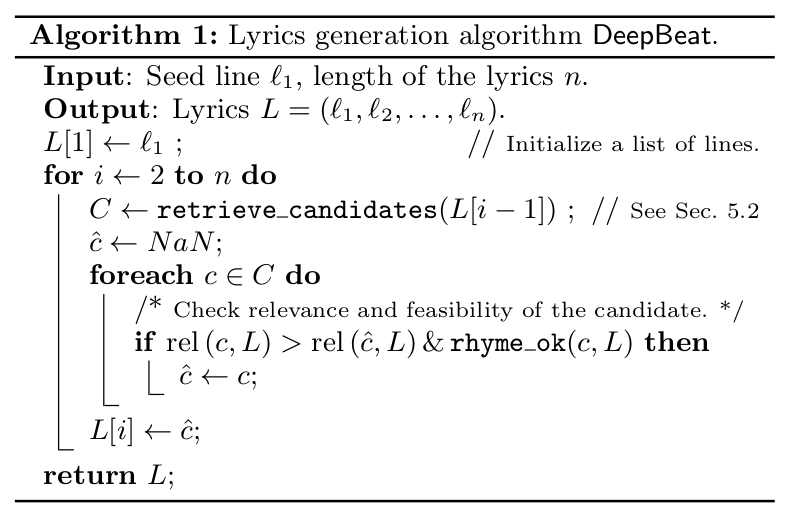

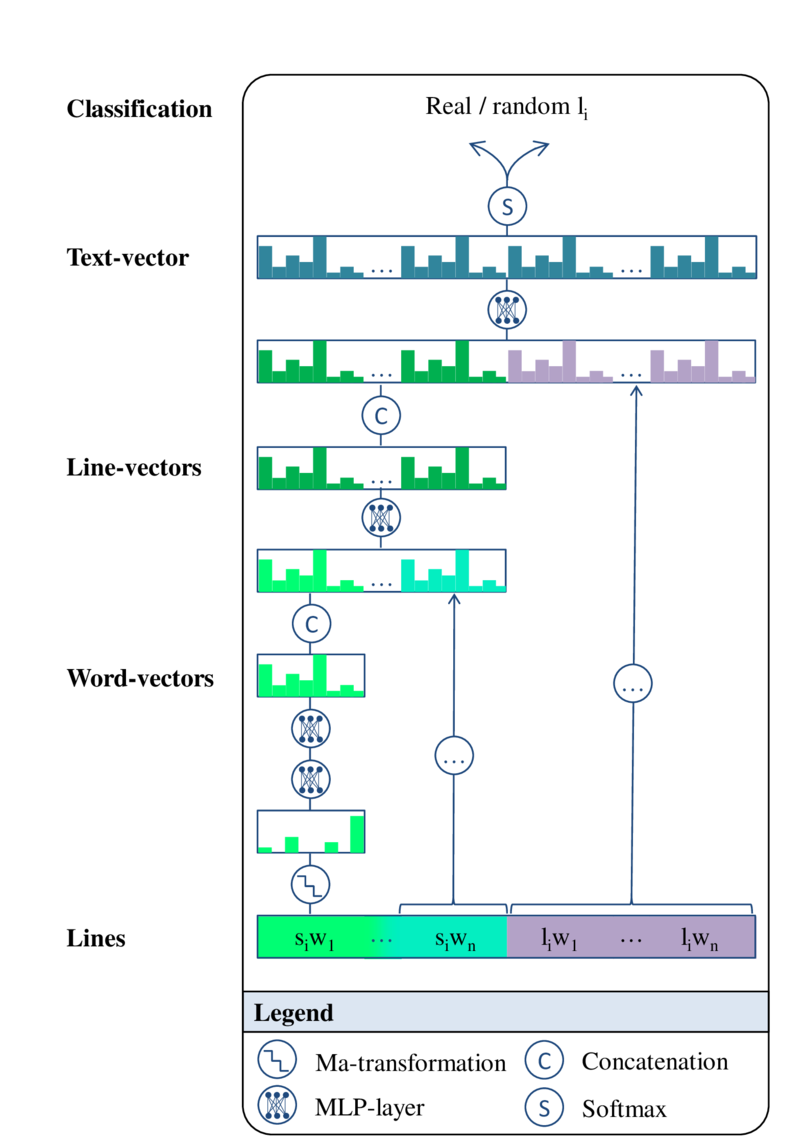

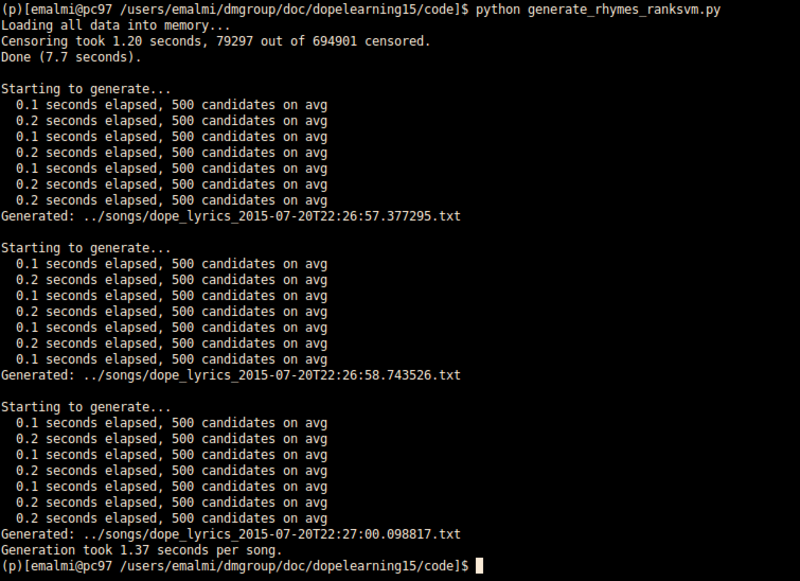

Created by Eric Malmi (and a few friends) at the University of Aalto in Finland, DeepBeat is a machine-learning algorithm that can write its own rap lyrics. Given a starting line of lyrics, it can recognize notable features and then choose another to follow that both rhymes and addresses a similar topic. Backed by a database of more than 10,000 songs–with almost 600,000 lines from more than 100 rappers–it has a huge chunk of hip-hop history at its fingertips with which to create something new. In short, where hip-hop traditionally samples music, DeepBeat effectively samples lyrics.

As Malmi told MIT’s Technology Review : “DeepBeat works like a search engine such as Google; it constructs lyrics line by line, using the previous lines as the search query and then finds the most relevant next line within [the database]. The relevance of a candidate next line depends on three factors: rhyming, length, and the semantic similarity [predominantly the incidence of assonance rhyme, a distinguishing feature of rap which is the repetition of similar vowel sounds, such as in the words “‘crazy’ and “‘baby’] of the lines. To quantify the meaning of the lines, in order to compute the semantic similarity, we have developed a deep neural network model, which maps the lines into number sequences, and then compares the number sequences rather than the lines themselves.”

The most difficult part of writing any song is getting started. Moving away from that blank page is objective number one, both musically and lyrically. This may come as a disappointment to some music fans out there, but rarely is inspiration found by staring up into the ever-expanding, limitless universe and getting struck with a gift from God. Normally, it’s achieved by copying someone else.

There are only 12 notes in the Western scale, and most professional songwriting sessions involve looking at the charts, seeing what’s working sonically, and using that as a jumping-off point: for a chord progression, for a tempo/rhythmic style, and for instrumentation. The hope, then, is that later down the line the song will veer off and become its own, distinct entity. So, in this respect, DeepBeat works like a human composer. You give it a keyword, it selects an opening line, and then off it goes for four verses, each consisting of four lines. By the 16th line, it could have trailed off in any number of diffferent directions–but will they all work?

To find out, I enlisted the services of a couple of rapper friends from a band I played in a few years ago: We were called Happy Attack–Essex’s first (and, to my knowledge, only) nine-piece, funk, hip-hop collective. We were very much a party, hip-hop act, so it made sense for our keywords to reflect that for our comeback song. Plus, Jurassic World–a major cultural touchstone if ever there was one–had just been released, so we would have been remiss not to include the word dinosaur in there, too.

Thus, Malmi received the words “super,” “party,” “crazy,” “disco,” and, yes, “dinosaur” with which to create magic. We were hoping to take advantage of a recent tweak to his algorithm which lets DeepBeat enlist multiple keywords–rather than just a starting line or word–to create more coherent lyrics. Malmi took two approaches: The first considered all rhyming lines as candidate next lines; the second considered only the top 10 percent of lines that were the most similar to the keywords, as determined by LSI topic model similarity. Both then had the constraint that all of the keywords must occur at some point in the lyrics.

What happened, in reality, is that DeepBeat produced pretty repetitive lyrics–particularly with the second approach–and the lines didn’t always flow into one another as we’d hoped. It also turned out that dinosaurs haven’t entered the lexicon of hip-hop as much as I had expected (just 31 lines in the popular hip-hop database refer to them), so the few dino-related lines were repeatedly shoehorned into the lyrics. It reminded me of Jason Derulo.

Onto an alternative. We next asked DeepBeat to provide separate sets of lyrics using single keywords: “crazy” and “party,” two words that have been popular in hip-hop since its earliest years. This worked far better, with a new batch of lyrics that flowed and made some general sense at first glance. Perhaps this isn’t surprising. Any human lyricist given four restrictions (or, in our case, four must-use words) is going to be compromised. For example, the A.I. might have had a good final line but couldn’t use it because there was an unused keyword leftover and it wouldn’t scan when added. Freed up a little, DeepBeat was able to go wherever it wanted, and it was all the better for it.

Meanwhile, MIT student Curtis Northcutt, a.k.a. rapper AXIS, approached me, keen to get involved. He chose somewhat weightier keywords for his lyrics: “life,” “pain,” “truth,” and “dream.” He too found that the 10-percent LSI restriction gave bad results, but a 50-percent version, offering the machine more freedom, proved much more effective.

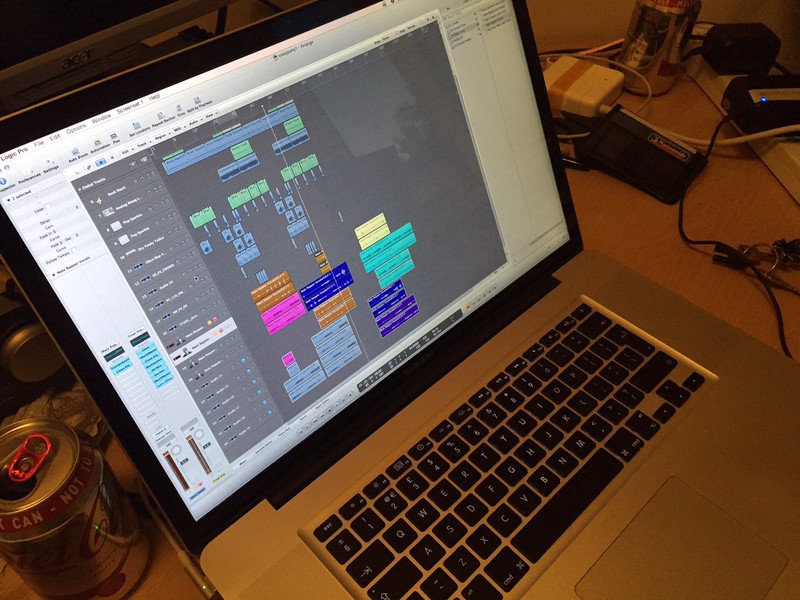

It was time to create beats to match the mood of the keywords. When someone says the words “crazy party hip-hop,” there’s only one record that springs to mind for me–Snoop Dogg’s classic Dr. Dre-produced 1993 debut Doggystyle . That record has a number of distinct musical elements to it: a lazy pace, a heavy bassline with plenty of chromatic notes, a funky groove, and Dre’s classic analog lead sound. Plus, if you’re going to sing about parties, you may as well have the actual sound of one on the record. That means crowd noises and whooping, along with some hip-hop “heys.” And, nothing screams “party” more than a vibraslap. (We did consider enlisting my friend, a DJ scratch master, to add a few cuts, chirps, and crabs, but unfortauntely he was out of the country–although he did point out that if a computer was writing the lyrics, perhaps a computer should be doing the scratching, too?)

Now it was lyric time. We started by panning the hundred sets of four verses, each consisting of four lines, that DeepBeat had produced. Many verses just didn’t work. There were too many syllables in a line, or they didn’t flow, or consecutive lines were nonsensical. But we kept looking, and it didn’t take long to strike gold. There was one giant nugget: an entire 16-line set which formed “our” second verse. We borrowed from four seperate verses and joined elements together to create the first verse, while one particular quartet stuck out immediately as perfect for the chorus:

“Just tell me that you love me, I’ll say I love you, too, That slop you pop you need to stop, you’re kind of rude you, And I’m glad you love me “’cause I luv u 2, But I take it when you get naked* cause your body’s like boom! Boom!”

*[shortened to “you’re naked” for flow in the final song]

Why did it stand out? That was a purely human decision: It had the perfect balance of humor and memorability, and it just felt right.

Meanwhile, in Massachusetts, Northcutt adopted a similar approach but with a touch more precision, given that his subject was more serious than partying. He rapped along to a rough version of a simple, dark beat that I gave a choppy guitar hook, using Eminem’s “Lose Yourself” as a jumping-off point (a song I thought of as having similar themes to Northcutt’s keywords).

In assembling the verses, he sieved through, looking for those that flowed with the beat and had a suitable number of syllables, keeping two-line and four-line pieces together, before reordering to make sure the story made sense. After sending his recorded rap over to me, I found that again there was one eight-line set that immediately stood out as the chorus:

“The truth is in the building and I came tonight, I wonder if you’ll pay attention if I change the price, And all of you say I have a dream the dreamer, The mirror says you are the next American leader, This thug’ll balance beams just to smuggle, Just a lie to my people that’s caught up in the struggle, It’s always gonna be a struggle in this hustle, Xzibit shall hustle lift build muscle.”

We repeated this to make the chorus, with the backing track changed–fuller in the choruses, more minimal in the verses–to finish the track.

So, without further ado, here are both songs:

AXIS–”The Machine’s Turn”:

LISTEN: Happy Attack–”Your Body’s Like Boom”:

How did we fare? Well, despite our initial skepticism, it is impossible to say that the exercise wasn’t successful. While the algorithm is far from perfect–the issues with the number of syllables not matching up and the lines that struggled in isolation away from their parent song need addressing–it is also seriously impressive. Both songs ended up with lyrics that make sense, flow well, and are ostensibly new creations, with fairly little effort from us humans beyond selection and ordering.

Only hip-hop fans with the most encyclopedic knowledge of the genre will be able to identify the origin of each line. What is most interesting is that, for example, the line “but I take it when you’re naked cause your body’s like boom! Boom!” was simply a throwaway, mid-verse line in Ludacris’s original song but became the payoff line of the chorus in the Happy Attack track. And that’s true hip-hop culture: cutting and pasting together lesser-known elements to create something new that is larger than the sum of its parts.

Will computers replace humans in pop writing? Well, not yet. After all, selection, ordering, and chorus-identifying is no easy task–things still have to “feel right,” which is, as yet, beyond the reaches of a computer. But perhaps, armed with some knowledge of the words or themes most prevalent in the choruses of hit songs, and with more feedback from users, there’s no reason why it couldn’t learn and eventually be the Deep Blue of rap.

In the interim, there’s no doubt that it’s a terrific assistant for getting past that difficult starting point for writing a tune. Of course, a further intellectual jump would be for the machine to create original lines, rather than borrowing others, but why not start by learning from the best? After all, every artist begins by following the leaders in his or her field, just as poets begin by learning from Wordsworth and Keats.

The KLF argues that you can create a hit song using nothing more than its manual. Could DeepBeat eventually become The Manual for hip-hop? We wouldn’t bet against it.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Fast Forward section, which examines the relationship between music and innovation. Click the logo to read more.