A few years ago, I wrote an article about addresses: “There are about four billion people around the globe who don’t have a way to refer to their home, and for every single one of them it’s a major problem. No address means you’re essentially invisible to the state. Aid, legal rights, voting, and bank accounts are all outside of your grasp. It’s nearly impossible to start a business legally, let alone get anything delivered to that business. In an emergency, where do you direct the ambulance?”

One solution I discovered was being offered by a startup called What3Words, who were hoping to establish a new global addressing system by dividing the world up into three-meter squares and allocating each a three-word address. The gates of Buckingham Palace are at latter.humble.sooner, while my dog was born at puff.slurps.microwave. The idea was create a memorable way to reference any point on Earth, whether it has a street address or not.

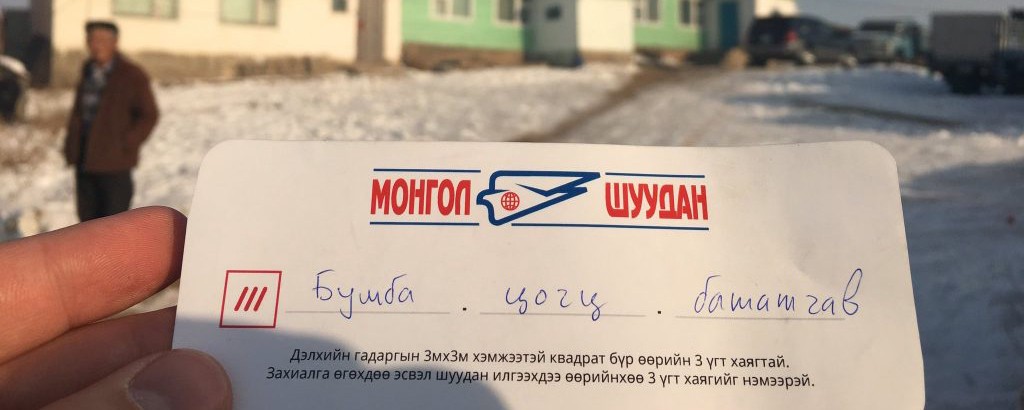

The system is being actively used in the real world. In Mongolia, the postal service uses What3Words to deliver mail and packages, and the Mongolian Automobile Roadside Service uses it to locate stranded drivers. In Germany, an aerial imagery firm uses What3Words to assess hurricane damage, while in Switzerland it’s used by the national public transport authority to locate bus stops. In the tiny Pacific archipelago of Kiribati, the mail service uses What3words to deliver to a population spread across 33 islands and atolls.

Around the same time that What3Words was created, Google’s Zurich engineering office was working on its own version of location encoding: the Open Location Code library, which became “Plus Codes” (it was during the heady days Google Plus). In Google’s system, locations are given a code that refers to a 14×14 meter chunk of ground–”about the size of one half of a basketball court,” the company says. By their coding, the entrance of Buckingham Palace is at 9C3XGV25+G6, and my dog was born at 9F9JCQVH+3G.

This week, Plus Codes were given a name-check in a blog post about an update to Google Maps India, which led to all sorts of publications reporting them as new, even though they’re not new at all. None of those reports really address the much more important question in my mind, which is whether or not they’re useful.

I don’t think they are. All the touted benefits–that they’re free, accessible offline, easy to use, non-exclusive, independent of borders, and identifiable–are already true of the latitude and longitude system invented by the Ancient Greek astronomer Hipparchus about 2,000 years ago. What3Words’ key advantage–that its addresses are easy to remember–is not true of Plus Codes.

Nonetheless Google dismissed both, along with other existing alternatives: “Latitude and longitude coordinates are still not widely used by people to specify locations. We think that this shows latitude and longitude have too many disadvantages to be adopted for a street addressing solution.”

I have two main problems with that argument. First, almost every bit of geocode in the world uses latitude and longitude coordinates. Addresses are a hard problem to solve in code, but lat/lon make it relatively simple. Saying that they’re not widely used is false. But even if you charitably append the phrase “in casual conversation” to the end of that claim, can you imagine using a Plus Code over the phone? It’s obfuscating a complex system with another complex system.

There’s no question that traditional street addressing systems don’t work on a global scale. Entire cities can rise and fall in the amount of time it takes to roll out a new addressing system for mail and service delivery, even in a rich, Western country–Ireland’s widely–criticized eircodes, for example, took about 16 years to implement. But Google’s Plus Codes offer no substantial improvements over latitude and longitude, and lack the alternate benefits offered by systems like What3Words. They seem to be a reinvention of the wheel that no one needs.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Going Places section, which looks at the impact of transportation technology on the modern world. Click the logo to read more.