I think a lot about archives. I’ve spent a lot of my career deep in the morass of digital magazine archives, with their byzantine file structures and “I’m sure this seemed like a great idea at the time” markup decisions and the Ghost of Content Management Systems Past and ancient mid-2000s technologies layered over prehistoric early-2000s technologies. I wound up working with archives first by chance and then by temperament: my brain sees a big messy pile of digital data and yearns to sort.

It wasn’t until grad school, in the digital humanities, where I started to really think about how we were sorting, and why–and even more fundamentally, what gets stored in the first place. The intersection of computer science and the humanities is a difficult field to pin down, but in my view, it often works one of two ways: using digital technologies to study the humanities, or using the humanities to study digital technologies. In either direction, there were a lot of archives to mull over: what to save, how to save it, and how to share it with the world.

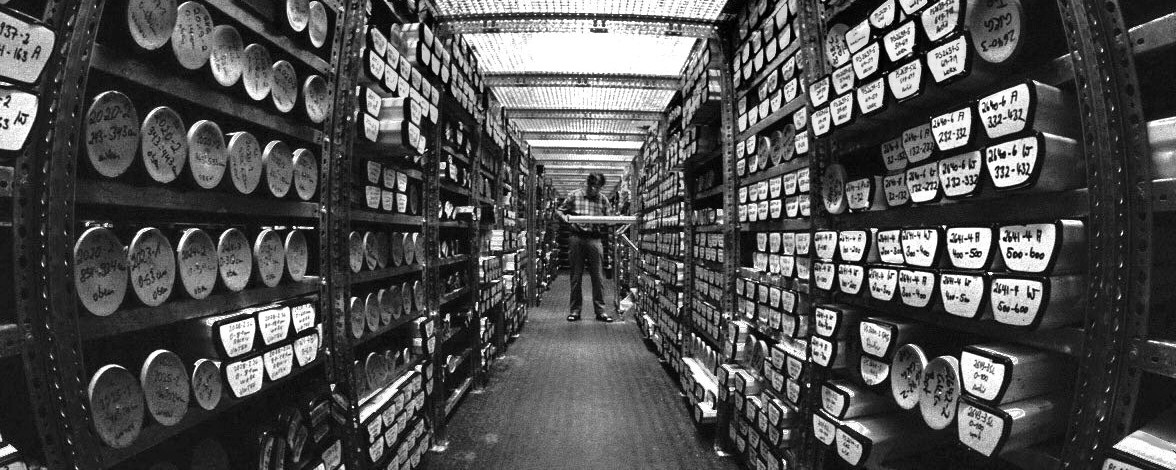

At the magazines I’d work for I’d never thought to question why we were converting and sorting through the contents of back issues: a magazine is its archives, the foundation on which the next issue is built, and the one after that, until those become the foundation for an issue in 50 years’ time. This certainty, as it turns out, isn’t all that helpful for making most archival decisions. Storage capacity–and human hours to create and manage archives–are far from infinite. At a magazine, much of the hard curatorial work is done long before the text gets digitized: if it makes it into print, it’s worth saving. But these questions are a lot harder when there was never any print at all.

I’ve been thinking about archives this week because of a recent piece, “Digital Media and the Case of the Missing Archives,” by Danielle Tcholakian at Longreads. (Side note: Longreads is commissioning some wonderful stuff these days; definitely make sure they’re on your radar if they aren’t already). Tcholakian’s piece was further inspired by a fantastic piece about digital news archives in the Columbia Journalism Review, “Erasing History” by Maria Bustillos, which I shared in this newsletter a while back.

Both pieces ruminate on the disappearing archives of online publications. The most well-known recent example is likely the shuttering of news sites DNAinfo andGothamist by billionaire owner Joe Ricketts, who closed the sites and fired everyone after employees voted to unionize. This in and of itself is horrific, of course, but a good portion of the outcry centered on the fact that the sites’ archives had been deleted as well; abruptly-fired writers had no proof of their past work to take out into the world to look for new jobs.

(The archives were bought and restored by WNYC–which, Tcholakian rightly points out, has been embroiled in its own transparency nightmares over the past six months–and now Gothamist has been Kickstarted back into existence, with $131,000 raised as of today.)

I understand why a lot of people in the media focused on those lost clips, that lost proof of work; I’m very grateful that the websites I’ve written for don’t seem to be in danger of yanking old content offline. But there are bigger questions underlying what we save on the web–what we can save, and who gets to make the decision to save it. The web gives us a lot of things that are unprecedented in human history, and one of them is the fact that we can hold on to, for lack of a better word, ephemera: the detritus of human life, recorded at unprecedented scale.

There is a sort of negligent impermanence to so much of what we put online. Quick hits, falling off the feed just as quickly. Whole platforms with impermanence built in, content meant to disappear after a set amount of time. What kind of stories are we allowed to record and keep? These words, the cultures we are creating with our infinite streams, form a sort of unsteady record of humanity at this moment in time. And what we keep–what we are allowed to keep–writes the shape of that history.

In her CJR piece, Bustillos writes beautifully about the value of the archive, of the power of massive piles of the smallest bits of news: “History is a fight we’re having every day. We’re battling to make the truth first by living it, and then by recording and sharing it, and finally, crucially, by preserving it. Without an archive, there is no history.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our The Internet section, where we report on the past, present, and future of the information superhighway. Click the logo to read more.