When the psychologist Robyn Stein DeLuca agreed to appear on the U.K. breakfast TV show Good Morning Britain last year to argue that PMS doesn’t exist, the producers must have been rubbing their hands together with glee. On the show–which is known for its combative and bullying questioning style–DeLuca said that while many people experience psychological and physical changes over the course of their menstrual cycles, in most cases these shouldn’t be considered a disorder, and they don’t require medical intervention.

Viewers didn’t appreciate what she had to say. “Stupid woman” and “I hope she gets the worst menopause ever” were just two of the numerous responses. To argue the case against DeLuca, Good Morning Britain had booked “author-turned-media consultant” Helen Croydon, who has no scientific training or expertise in the subject. She contended that Stein DeLuca was “giving men ammunition to say “‘it’s all in your head.'”

But DeLuca’s claim wasn’t baseless. New research challenges the extent to which hormones govern perceptions, emotions, and behaviors during the menstrual cycle. Last year Benedict Jones, a psychologist at the University of Glasgow, led a series of studies that aimed to replicate research from the last 20 years linking menstrual hormones to psychological state. Jones looked at much larger cohorts than previous studies–numbers of participants in the hundreds, rather than tens. The result was a string of “no evidence” papers, where their findings failed to uncover the same patterns indicated by those earlier, smaller studies.

“We weren’t confident that all of the big findings in the literature would replicate,” Jones explained. “However, we have been surprised at how few of them have.” Jones and his colleagues have torn apart numerous assumptions, including that fluctuating hormones govern the kinds of faces people are attracted to, care taken over hygiene and cleanliness, and a desire for uncommitted sexual relationships.

One study Jones was involved with–which has yet to undergo academic peer review–casts doubts over the supposed link between the hormone progesterone and feelings of anxiety or jealousy. Jones’s research seemed to contradict the work of Tania Reynolds, who carried out one of the first human studies on the topic and found a link between the hormone and how secure people felt in their romantic relationships.

Reynolds told me about the evolutionary hypothesis behind her work: “Progesterone is a hormone that increases towards the end of the cycle”¦ it promotes changes in the body that prepare it for pregnancy. There are a lot of costs associated with pregnancy–your caloric demand goes up, your mobility is limited, you need to rely on your social partners. So perhaps our minds might shift: Do I have enough social support for pregnancy? Is this a social environment that is going to be conducive to having a favorable pregnancy? Perhaps, in humans, progesterone plays a social vigilance role where we pay attention to our social support.”

Reynolds pointed out that Jones’ study examined slightly different measures of anxiety and used a different methodical approach. Jones agrees that the work wasn’t a direct replication, but he argues that when viewed together, his and Reynolds’ studies show “that there probably isn’t a clear link between progesterone and anxiety. If it’s there at all, it seems to be specific to certain types of analysis and certain aspects of anxiety.”

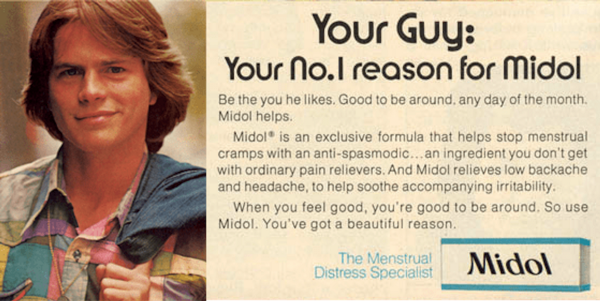

The trope of a hormone-driven woman whose emotions are not to be taken seriously is as old as medicine itself. Hippocrates proposed that women’s wombs wander around their abdomens, causing a host of illnesses including depression and madness. In 2015, after Fox News host Megyn Kelly questioned Donald Trump on his history of misogynistic comments, he accused Kelly of being in a hormonally-induced rage. “I just don’t respect her as a journalist,” Trump told CNN’s Don Lemon. “You could see there was blood coming out of her eyes, blood coming out of her wherever.”

I was keen to ask Reynolds about the possible sexist ramifications of her work–could her results be used to justify such comments? She pointed out that the reported fluctuations in anxiety were “very subtle”¦ it’s not like someone who is not at all anxious one day is going to be an anxious wreck the next day.” Jones and Reynolds do agree on the need for further studies. Reynolds highlighted the potential benefits of understanding hormonal influences on mood, citing the successful use of estrogen patches to alleviate the symptoms of postpartum depression.

The most cutting edge, robust and large-scale research seems to point towards the fact that the answer to the question of “how much behavior is controlled by the hormones of the menstrual cycle?” is “very little indeed.” This may be a hard truth to swallow for many people, including the viewers of Good Morning Britain. It’s easier to dismiss negative emotions such as jealousy, anger, and sadness as hormonal rather than addressing underlying causes, including economic circumstances, racism, sexism, or queerphobia.

The feminist psychologist Joan Chrisler has long-argued that PMS is a “culture-bound syndrome,” proposing that the label of “PMS” gives people permission to express the “unfeminine” emotions they are conditioned to suppress at other times during the month. Perhaps we should accept that most of the negative emotions we attribute to our hormones are indeed “all in our heads”–but for legitimate reasons rather than being mere biological artifacts.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Vital Signs section, on the future of human health. Click the logo to read more.