Read the next installment: “Fact, Fiction, and the Future”

Read the previous installment: “The Beginning of the Future“

In 1945, the United States was a very different country from the one that had entered the Second World War four years earlier. The drive to victory had sparked innovations in medicine, materials, computing, and, of course, weapons. And as the war’s end became an inevitability, minds began to turn to how these innovations would shape peacetime–and in the process, an unlikely industry was booming.

Life for most Americans during the war was one of sacrifice to support the war effort: strict rationing, limited consumer choice, and minimal leisure time. It was a world that should have been inhospitable to the advertising industry–items companies sought to sell were often unavailable to average consumers. Advertising agencies were left with a tricky question to answer in campaign briefs: how to sell to the consumer when they often had nothing to sell?

The answer lay in the future. Both ad agencies and their clients could see the war’s end on the horizon–with peace they saw a future of prosperity, and consumers ready to spend. While the war continued, brands were keen to stay in the public consciousness, giving Americans hope for the future; they promised a peacetime world of leisure and relaxation, thanks to fantastical-time saving devices. They were selling the American future–and, in turn, selling themselves and their products as key parts in the foundation of that future.

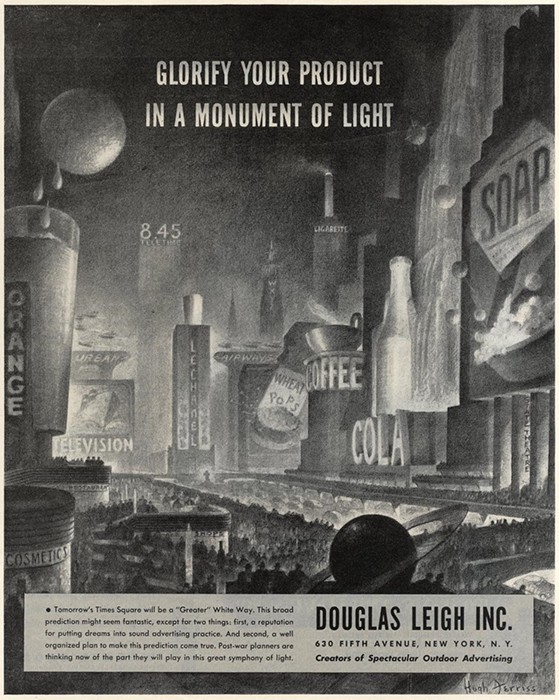

The prime medium for advertising was print. At its high point in the 1940s, Life magazine had a staggering circulation of 13.5 million readers every week, and it was through this and similar publications that brands broadcast their role in shaping the brilliant glorious future. The cynical and satirical portrayals of technology seen in an earlier age were gone: this was a future that was both aspirational and achievable, something within the grasp of the average American.

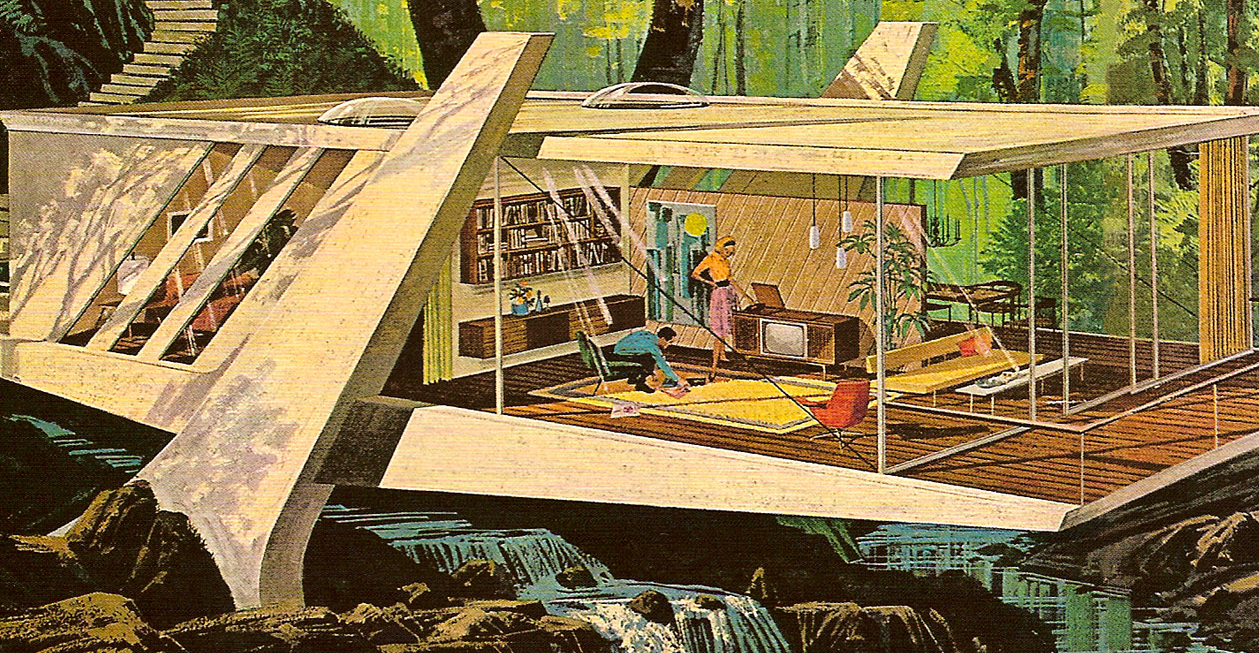

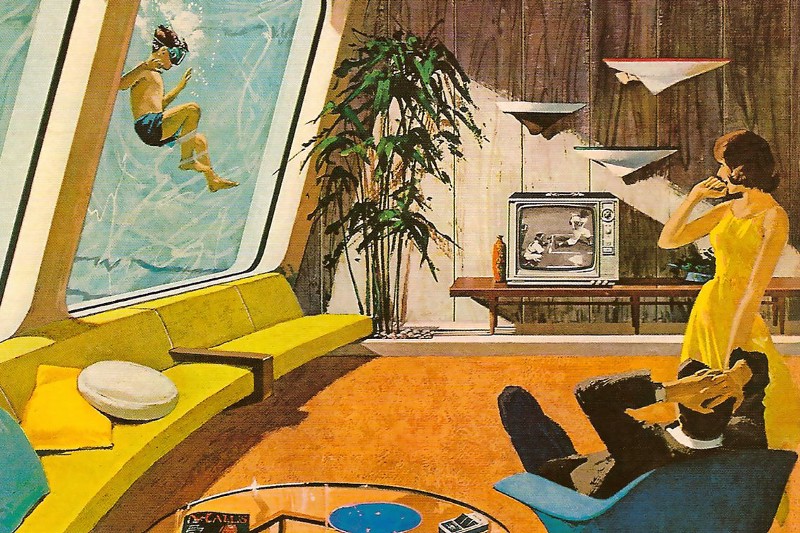

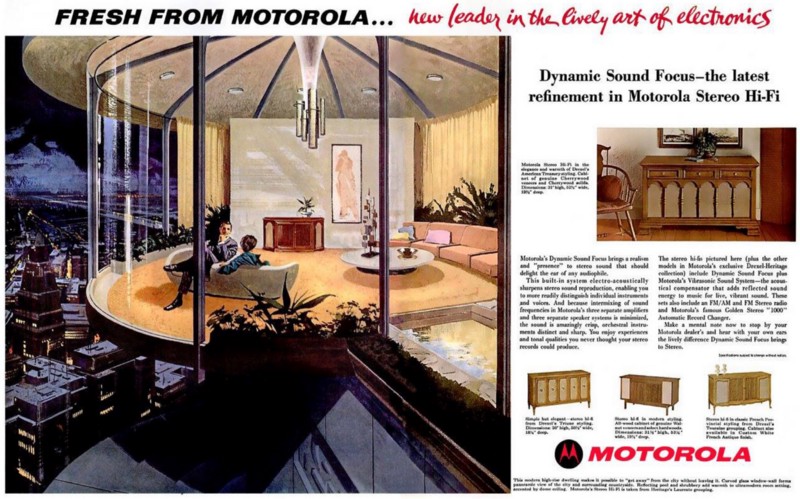

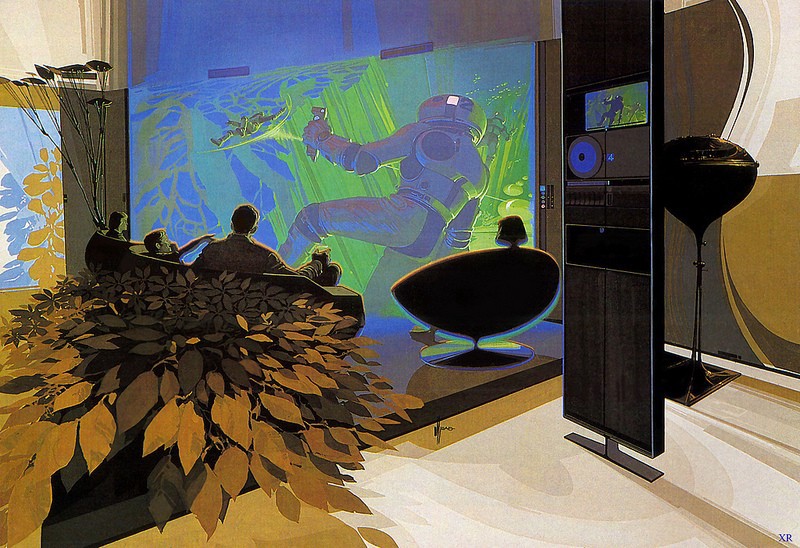

Capturing the imagination of the American public would involve reaching them through the common element they all shared: domesticity, placing recognizable products in a desirable domestic environment. Readers of Life and The Saturday Evening Post saw Motorola’s “House of the Future” campaign, which aimed to sell luxury electronic items: hi-fi systems and televisions.

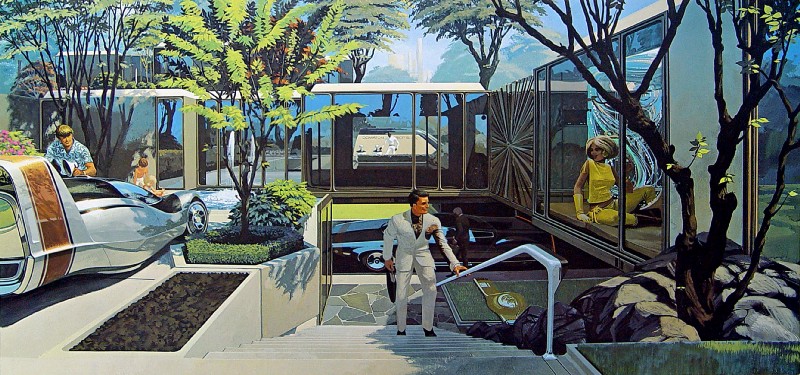

The homes were painted by artist Charles Schridde, who landed the account through an in-house competition, which asked artists to create “a neat place to watch TV.” The abodes he devised are closer to a Ken Adams-designed Bond villain lair than anything most Americans would live in, but then who wouldn’t aspire to have an underwater living room?

The most current televisions, and hi-fi systems in wooden cabinets, are the focal point in every living space. As real products in these exotic-looking spaces, they now look anachronistic in their futuristic setting. Their positions as desirable objects are dated by their futuristic surroundings, which are untethered by practical product design, engineering, or real estate restrictions.

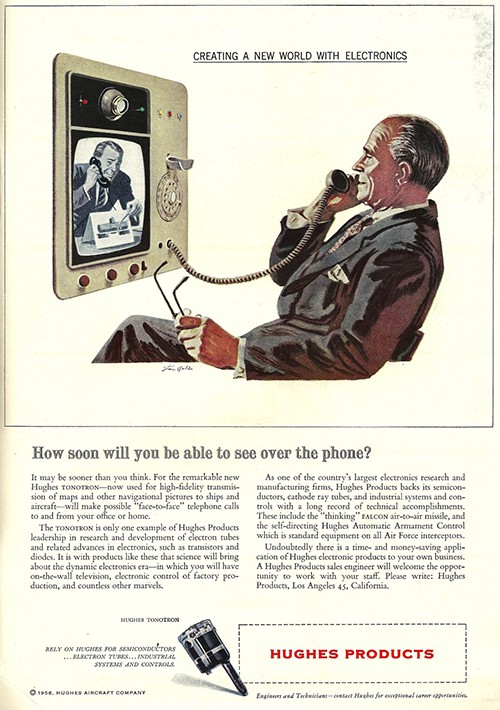

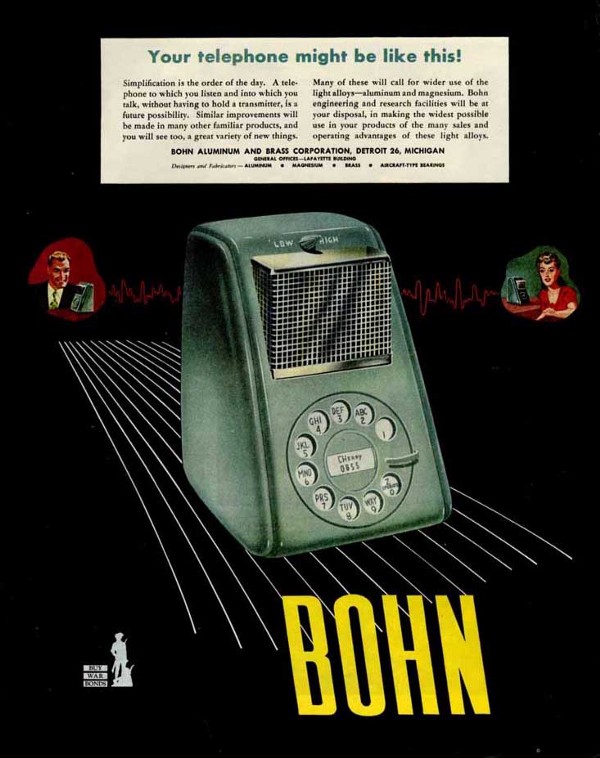

Companies with fewer consumer-facing products didn’t have to place them in everyday settings. Instead, they tried to carve out spaces for themselves in the future, suggesting where their materials could help the next big thing become real. If Motorola had real televisions to sell, Hughes could focus on the evolution of the TV screen–if we could hear each other at a distance with telephones, surely the next step would be to see who we were talking to?

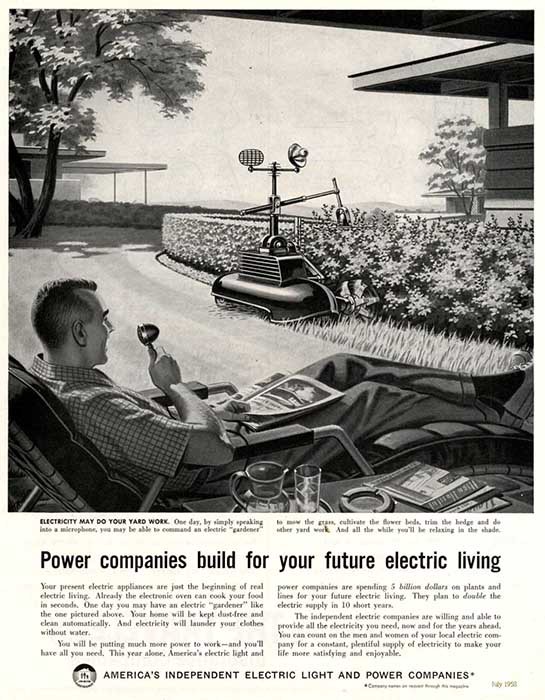

If Americans were to enjoy more time with their new televisions, they would need to be liberated from the drudgery of domestic tasks. Tedious work such as mowing grass or trimming shrubs could be taken care of without leaving the lounge chair, using a microphone to instruct your mechanized labor force while you kicked back, drank, smoked, and read magazines.

New Departure Ball Bearings (“Nothing Rolls Like a Ball”) started out making ornate door bells in 1888. By the 1950s, their ball bearing components played an important part in the labor-saving machines of the near-future. Time spent preparing meals would be next to nothing when “SUPER CHEF” took your favorite ingredients from a vast freezer and zapped them onto a conveyor belt with an infrared ray.

Laundry that washed, dried, and folded itself would leave so much more time for socializing and leisure.

Every image is a domestic utopia: rolling green hills outside the windows, bright colors, everything new and clean. Who wouldn’t want to live in this shiny new future after years of “making do” through the war and its aftermath?

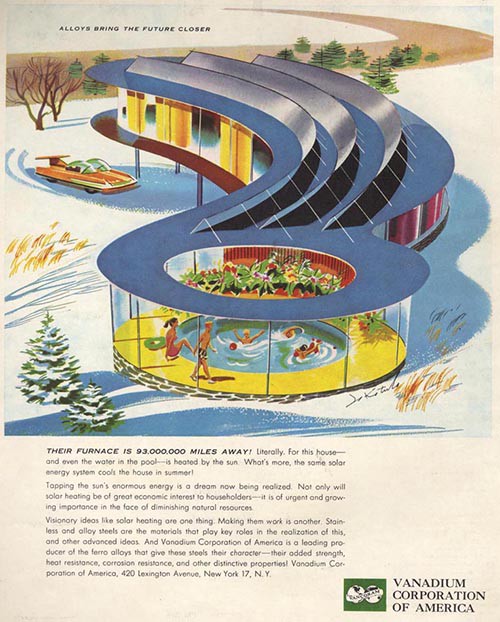

For companies that made unglamorous products like metal, power, and electronic components, it was vital to predict a future in which they would play starring roles. This strategy also consolidated many brands’ positions as integral to forging tomorrow; these companies had the longevity to deliver on their promises.

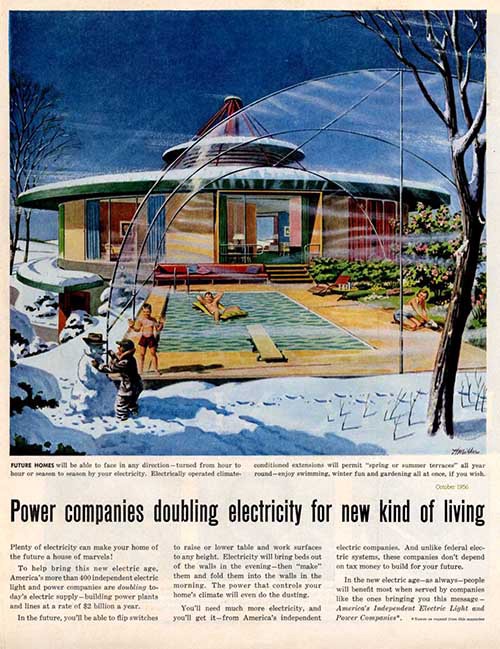

How that would be achieved depended on what was being sold. Steel alloys could play a key role in powering the home with solar energy. Privatized power could help mechanically lower beds out of walls–or create summer indoors all year long.

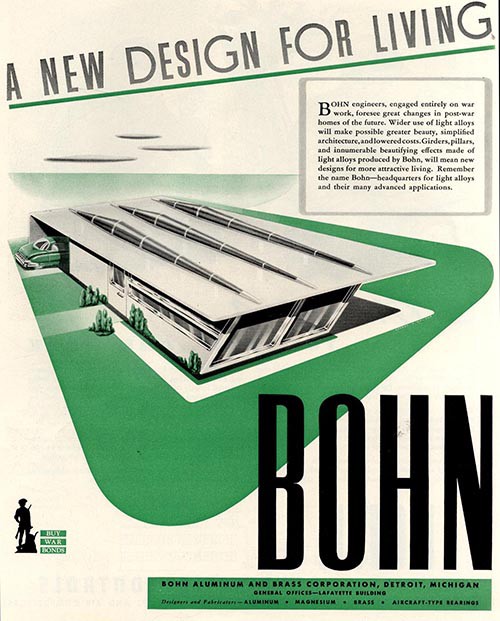

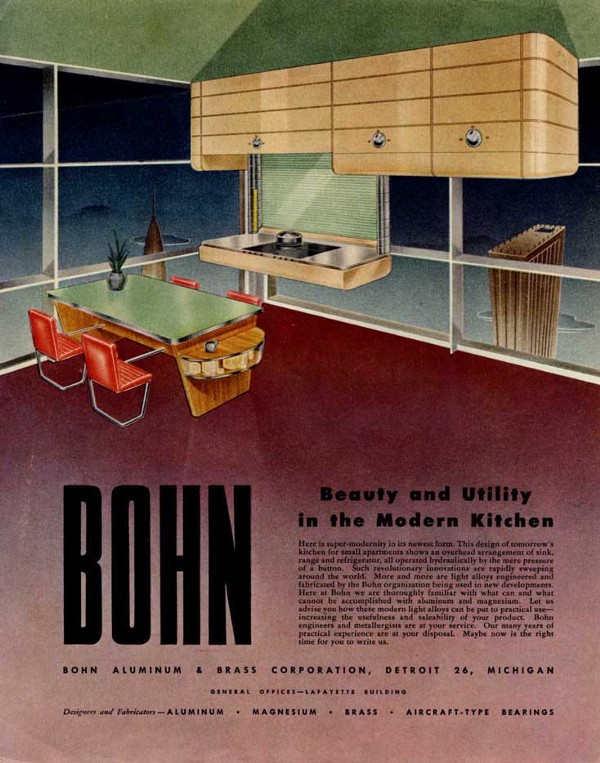

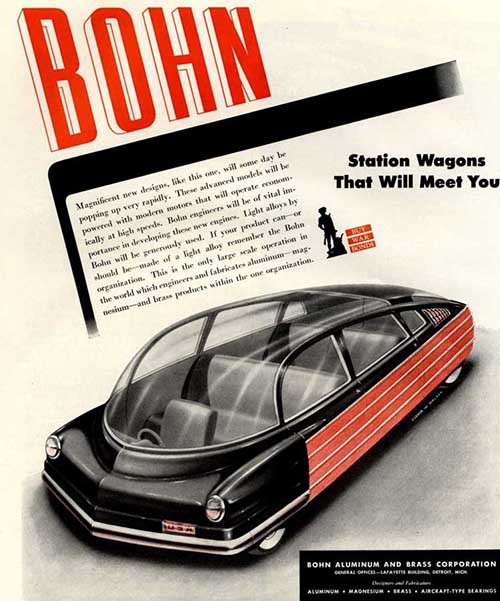

Detroit-based Bohn Aluminum and Brass Corporation started a long-running futuristic campaign in the 1940s. Their mission was to make Americans “remember the name Bohn–headquarters for light alloys and their many advanced applications.” Light alloys were the miracle material that would open the gateway to a revolution in everything from farming to basic living standards.

Many of the images were created by artist Arthur Radebaugh. Everything is smooth lines and bulging curves, bright materials and science-fiction-like settings–even kitchens seem to float miles above the ground, dwarfing nearby skyscrapers.

Nothing symbolized American postwar prosperity more than the rise of the automobile: the archetypal status symbol of American wealth and luxury. For Bohn, Radeburgh mixed ideas of domestic life and industrial design to create glass-roofed, self-driving cars.

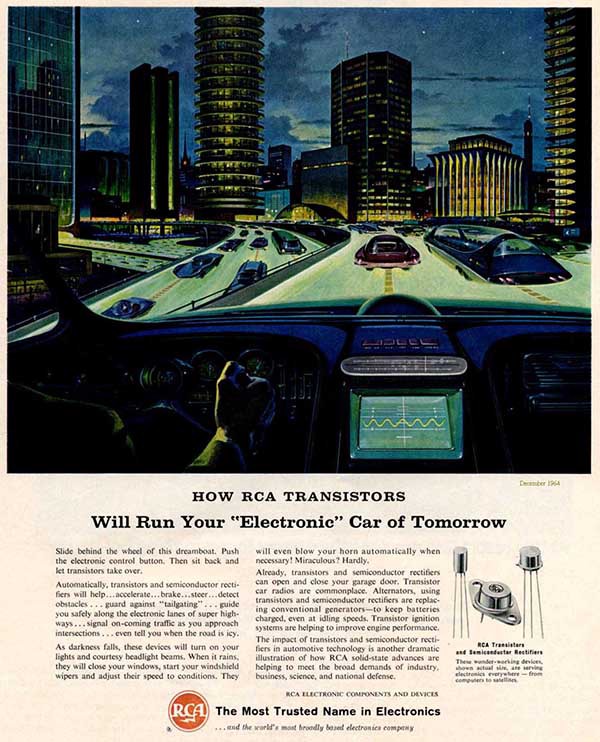

Radeburgh was also behind a first-person perspective 1964 RCA advertisement in which the viewer could, “slide behind the wheel of this dreamboat. Push the button. Then sit back and let the transistors take over.”

It wasn’t long before ideas about the car took to the air–futurists refuse to stay grounded for too long–and America’s Independent Power and Light Companies would be powering the transport revolution.

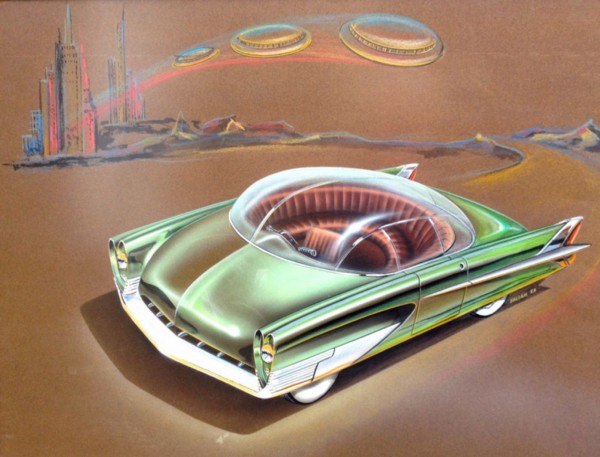

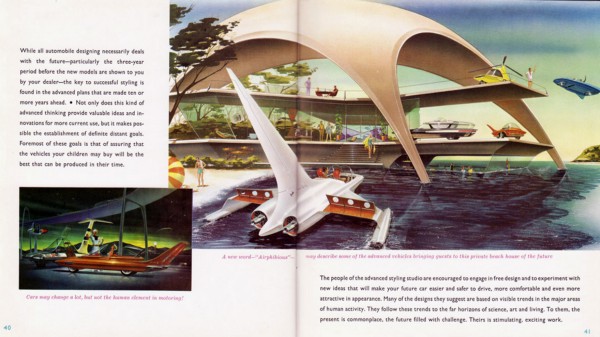

Car companies like Ford’s Advanced Styling Studio gave artists “complete freedom of expression” to explore new shapes and ideas free from standard conventions.

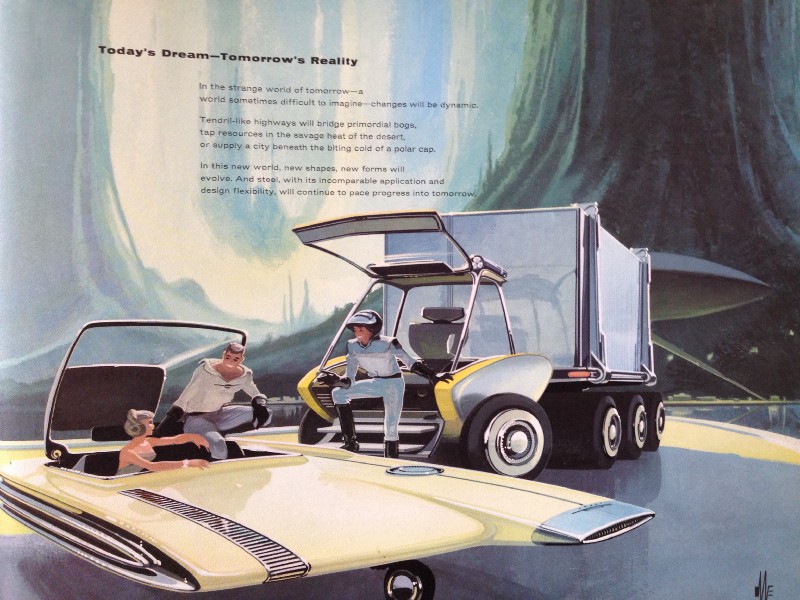

Luxury and leisure are still a big part of the sell, but the specifics on how this technology would work took a backseat. “This car is quite obviously powered by some unknown propulsion system as yet undiscovered on Earth,” Alex Tremulis, 1955 studio chief, said. “There is no doubt in our minds that most of these designs can be readily refined and developed into successful automobiles.”

One of the Advanced Styling Studio’s most famous graduates was Syd Mead. Known for his iconic concept designs on Blade Runner, he started his career under Elwood Engel at Ford, where he worked until 1959. His ideas about automobile design remained a strong theme throughout his career, but it was his holistic approach to presentation that dropped these ideas into a fully-formed, often aspirational world.

He created worlds of sleek lines, exotic futuristic sports cars, and life inside glass “residential city modules.” Though his futures strived to be “bright, functional, well-conceived, and consistently elegant,” his description of the creation process was far less hi-tech: “I put pen on board with animal hairs on the end of a stick.”

He imagined not just the vehicles but the roads they’d be driven on: “In the strange world of tomorrow–a world sometimes difficult to imagine–changes will be dynamic”¦.Tendril-like highways will bridge primordial bogs, tap resources in the savage heat of the desert.”

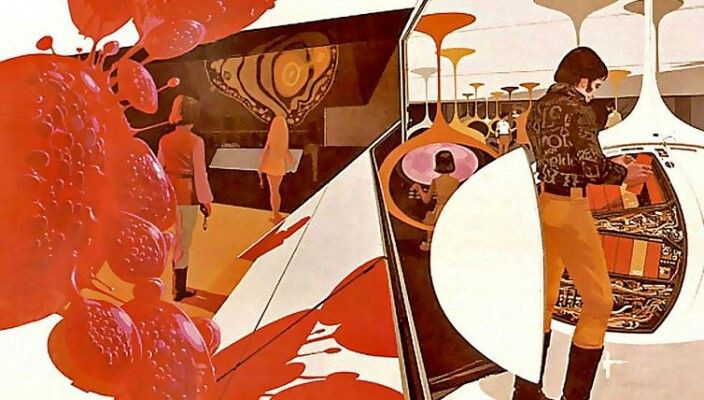

In the early 1970s, Knut Yran brought Mead on to help Phillips answer the questions, “How can we make the world more livable?” and “How can we improve and re-humanize the things and environments around us?” They sought answers untethered from engineering and manufacturing considerations, through a process they referred to as “wild-cat dreaming.”

Some of the resulting ideas were inspired by contemporary real-life concerns like illiteracy and teacher shortages. The multimedia center depicted in the next picture aimed to solve that by allowing students to access stylish hanging learning modules–all while dressed in the height of 1970s fashion, of course.

Living spaces remained an important focus, and Phillips envisioned futuristic domestic scenes, with clean, minimalist lines.

The future of home entertainment would be holographic, wall-sized 3D technology and “swivel-out wall cabinets producing a dense linearized screen of ionized air particles between two aligned cabinet slits.”

After World War Two, artists and advertising agencies wanted to sell a bright and hopeful future. But they were also working to produce something that their audience would recognize and find plausible. As H. G. Wells said: “Anyone can invent human beings inside out or worlds like dumbbells or gravitation that repels. The thing that makes such imagination interesting is their translation into commonplace terms and rigid exclusion of the other marvels of the story. Then it becomes human.”

Of course they couldn’t anticipate all possibilities. Some objects are notable by their absence: computers don’t really feature as part of everyday life, despite their rapid growth in industrial spaces in the era. Looking at these living spaces, no artist could envisage how ubiquitous the game console would be, side-by-side with the television in our leisure hours. And in the majority of these images, the future is almost entirely white, with clearly-enforced “traditional” gender roles. Most of these ads, like many ads in general, wanted to offer an aspirational vision of a future America–and, for the advertising industry at that time, that typically meant white, suburban and middle class.

But these images served a purpose: as Mead put it, “what we do now actually invents the future.” Each new concept had a potential audience of millions, and they offered ideas about the small and large ways in which everyday American lives could change for the better. It’s difficult to prove direct links from these images to our present, but it’s undeniable that they helped contemporary American consumers think about the world to come.

Read the next installment: “Fact, Fiction, and the Future”

Read the previous installment: “The Beginning of the Future“

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. A Visual History of the Future is a five-part series on the way artists’ visions of the future shaped the world we now know.