Read the next installment: “Birds on the March: The return of avian influenza”

Read the previous installment: “Inception: The avian flu outbreak in Hong Kong, 1997“

Spring 1918 and the battlefields along the French-Belgian border were lumpy with bodies. These men had not been laid low by shells or by bullets. Their attacker was an unseen scourge, one that lived in the rivers of mud, blood, and piss that dribbled through the trenches, one that hung in the very air.

Kaiserschlacht was the name given to Germany’s final offensive lunge in the Great War. General Erich Ludendorff was a commander with deep-set eyes, a 19th century villain’s twirled mustache, and an anti-Semitic bent. He’d ordered Germany’s troops to the Western Front with the hope that they might turn the tide of war before the Americans arrived to bolster French and British forces. It was a sound plan. Then the infections began.

The flu’s effects were like spells cast by a cruel and imaginative fairytale witch. Most commonly, people’s hands and faces turned a pale shade of lavender, the result of a condition known as heliotrope cyanosis. After a few days, some victims’ skin turned black, before their hair and teeth fell out. Others gave off a curious smell, like musty straw. One medic described seeing men choking to death, “the lungs so swamped with blood, foam and mucus that”¦each desperate breath was like the quacking of a duck.” The American novelist Katherine Anne Porter survived, but not before her ebony hair turned irrevocably white.

In the trenches, the infections were catastrophic–not just for individuals, but for armies. By the end of the spring, 900,000 German soldiers were out of action, puncturing Ludendorff’s plans (though after the war, the general blamed disloyal Jews for Germany’s defeat). But the virus respected no battle-lines, ideology, or allegiance. Within weeks as many as three-quarters of French troops had also fallen sick, and more than half of the British force succumbed as well. It wiped out entire units, filling makeshift hospitals with feverish soldiers. “We were lying in the open air with just a ground sheet and a high fever,” recalled Donald Hodge, a surviving British private.

The flu spread quickly and, according to the World Health Organization, “killed more people in less time than any other disease before or since.” It was 25 times more lethal than most flu pandemics, which are already many times more deadly than seasonal flu. It tore through the trenches like wildfire–one that may have burned itself out were it not for the ceasefire in November 1918 that sent millions of infected soldiers home, carrying the virus to the four corners of the world with military efficiency.

As the flu spread around the globe it left a tapestry of grisly scenes in its wake. In Rio de Janeiro, gravediggers couldn’t work fast enough to bury all the bodies; one man, while out on a walk, described seeing a human foot “suddenly blooming” out of the earth. In one Alaskan village, the number of dead could not be estimated because starving dogs, whose masters had succumbed to the disease, had dug into huts and devoured the dead.

As the disease and its extravagant symptoms spread, it acquired a confusing list of monikers. Each nation it infected devised a label that apportioned blame to another group, a way to simultaneously distance themselves from being labeled the source while, in many cases, adding notes of xenophobic cultural superiority. In Senegal it was known as the Brazilian flu; in Brazil the German flu. In Germany it was known as “Blitzkatarrh,” or lightning cold, while, to Spaniards, the epidemic became “the Naples soldier.” English soldiers fighting in France used the term “Flanders grippe,” while the Iranians blamed the British. The Japanese, curiously, blamed the wrestlers; the country’s first victims were sumo stars. The New York Times, in June 1918, described the virus in a headline as a “queer epidemic” sweeping northern China.

In the end, geopolitics gave the virus the name that stuck. Even though it didn’t show up in Spain till May 1918, the country, which was neutral in the war, had no tactical reason to suppress news of any flu-related deaths. While the British, French, and Germans pretended that their respective troops were immune, the Spanish media openly reported on its flu victims. A scapegoat had volunteered itself. Thus, a global pandemic was duly and strategically branded as a local concern: the Spanish flu.

By the time the disease fizzled out almost three years later, as many as 100 million people had died–a higher toll than that of both World Wars combined. The virus killed more people in 24 months than AIDS killed in 24 years, more in a year than the Black Death killed in a century. It caused, as Laura Spinney, the author of Pale Rider, a recent book on the pandemic puts it, “the greatest tidal wave of death” that humanity had seen in more than 500 years.

For the past century, historians, epidemiologists and virologists have worked to find when and where this virus originated. Three dominant theories remain in contention, along with one smoking gun.

The first and oldest theory began contemporaneously. Military doctors treating victims on the front believed that the Spanish flu came from China. “Everything came out of the far east,” Spinney told me. “Chinese people were believed to have poor hygiene.” In time the theory was dismissed as a racist stereotype–after all, how would a virus leave a relatively closed-off, rural country? But more recently historians have argued it is at least feasible.

The oft-overlooked Chinese Labour Corps was a group of 95,000 Chinese farm laborers who volunteered to leave their remote villages and support the British war effort. Many worked behind lines for the Allies, assembling shells, repairing tanks, and so on. They traveled by ship via Canada or South Africa, circling the world–the perfect vehicle for transmitting a respiratory virus.

John Oxford, a professor of virology at Queen Mary’s School of Medicine in London, cleaves to a different theory: one that fingers patient zero among British troops stationed in France. In 1914 the British army built a training camp in Etaples, France. It was a notorious place–”a vast, dreadful encampment,” as the poet-soldier Wilfred Owen put it–where men carried a look “more terrible than terror”¦ like a dead rabbit’s”. The camp had twenty-four hospitals to tend the wounded, and among the staff a team of pathologists.

In December 1916, a flu epidemic hit the camp, killing around 40 percent of those infected who, before they died, turned the tell-tale shade of lavender blue. Etaples was home to hundreds of thousands of birds: there are scores of photographs showing the men plucking chickens, ducks, and geese. Could it have started in this camp, the perfect incubator for a virus to grow more virulent and while, at the same time being contained until it had acquired the ability to transmit between human beings?

The most likely source, however, is a farm in rural America. In March 1918, Albert Gitchell, a mess cook at Camp Funston, a U.S. Army base in Kansas (now Fort Riley), checked in to the camp infirmary complaining of a sore throat, a headache, and a fever. By lunchtime, the infirmary was full of soldiers complaining of the same symptoms. Within a month, so many had reported sick that the camp’s medical officer had been forced to requisition an aircraft hangar to house everyone.

John Barry, in his 2004 book The Great Influenza, unearthed an outbreak of respiratory disease two months before the breakout at the camp in Haskell County, a few hundred miles east of Camp Funston. It was a vicious outbreak, so exceptional that one doctor chose to report what was happening–the first recorded instance anywhere in the world of an outbreak of influenza so unusual that a physician warned public health officials of its emergence.

Haskell County was tremendously poor, principally populated by farmers who lived in close proximity to their birds and pigs. The most persuasive theory about the origin of Spanish flu is, then, that a young man from Haskell County caught the virus from some poultry (perhaps via an intermediary pig), was recruited to the US expeditionary forces, and carried the infection into the heart of American war machine.

Almost a century later, three things are certain: that the first confirmed case of Spanish flu occurred, that it originated not in Spain but probably in Kansas, and that the pandemic started not in humans, but in birds.

As well as the logistical argument for how Spanish flu was caught and spread, there is the molecular evidence. Flu viruses are incredibly mobile, creating mutations constantly–this is the reason that we currently have to update our vaccines every year. But this also means that within the virus is the means of tracing its history. “Scientists know that within the host, the virus accumulates mutations at a constant rate,” explains Spinney. “They can extrapolate backwards from that rate and work out which viruses were closest to each other in the past, work out the family tree and the parentage of a given strain.”

Michael Worobey at the University of Arizona has spearheaded the work of creating a family tree of every flu virus that has circulated in humans and other species in the past 100 years. Through this work we know that the strain that caused the Spanish flu is highly similar to a strain circulating in birds in North America at that time. Like H5N1 and H7N9, the Spanish flu virus found a way to latch onto humans.

Regardless of its origin point, what remains striking about this hundred-year-old pandemic is how fast and how far it was able to travel in a world without mass air travel. After all, most of these deaths occurred in a 16-week period, from mid-September to mid-December of 1918.

Spinney believes that the virus may have adapted to take advantage of the circumstances of war. “Most viruses moderate themselves in order to keep their hosts alive long enough to spread through coughs and sneezes,” she says. “But the peculiar circumstances of the Great War, where its hosts were packed together in trenches, their lungs weakened by mustard gas, dying in droves of bullets and mortars, meant that the disease’s best chance of survival was to become unusually virulent.”

Between the spring and summer of 1918 it’s likely that the virus mutated through thousands of rounds of evolution between human beings, becoming ever more transmissible and deadly.

For epidemiologists today, the Spanish flu continues to provide a looming, cautionary tale. In the wake of the disease, many countries revamped their systems adapted to ensure there would never be repeated.

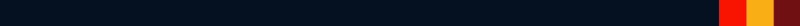

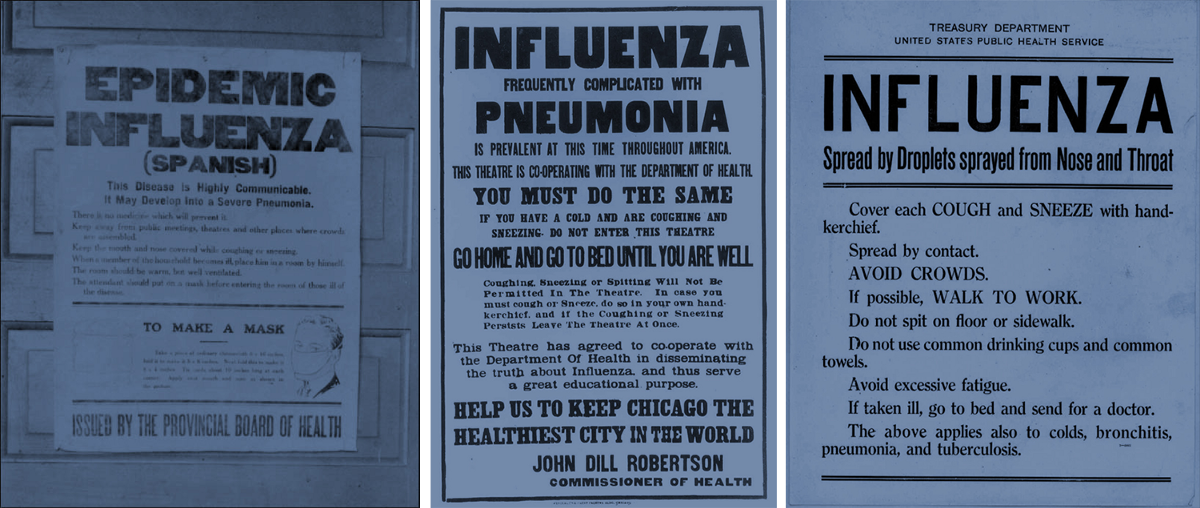

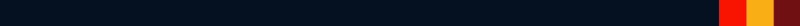

Prior to 1918, government departments of health had been reliant on other ministries for their money and power. After the Spanish flu, many became separate entities, in order to better manage a pandemic in the time frame required. The collection of health data became systematic. Doctors were now obliged to report influenza outbreaks. Epidemiology became a cornerstone in public health. Russia introduced a primitive universal health care system in 1920 and other countries soon followed its example–an acknowledgement that, in a pandemic situation, you can’t blame an individual for catching a contagious disease, or treat him or her in isolation. Society must be treated as a whole.

This principle has not always been upheld in subsequent pandemics: the AIDS crisis, for example, was marked by moral blame and the ostracizing of its early victims, most of whom were gay men and heroin users. President Reagan’s first mention of the disease was in 1987, after more than 25,000 people had died in the United States.

Unfortunately our developments in medicine, healthcare, and preparedness have been countered by other developments that today stack the deck more in favor of a deadly virus. Our schools are incubators for disease among young, healthy children. Our roads, which carry trucks laden with animals and humans, have become fast lane tributaries sweeping viruses from one city to the next. And the democratization of air travel has enabled a virus to cross hemispheres at a speed that would have been unthinkable in 1918.

The question now is how such a virus might be slowed, in a world that spins ever faster.

Read the next installment: “Birds on the March: The return of avian influenza”

Read the previous installment: “Inception: The avian flu outbreak in Hong Kong, 1997“

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. Fowl Plague is a five-part series that explores the history of deadly global pandemics–and asks whether we’re ready to respond to the next one.