Read the next installment: “Foreshadowing: How avian flu shaped the Great War“

Read the previous installment: “Pandemics: A Reading List“

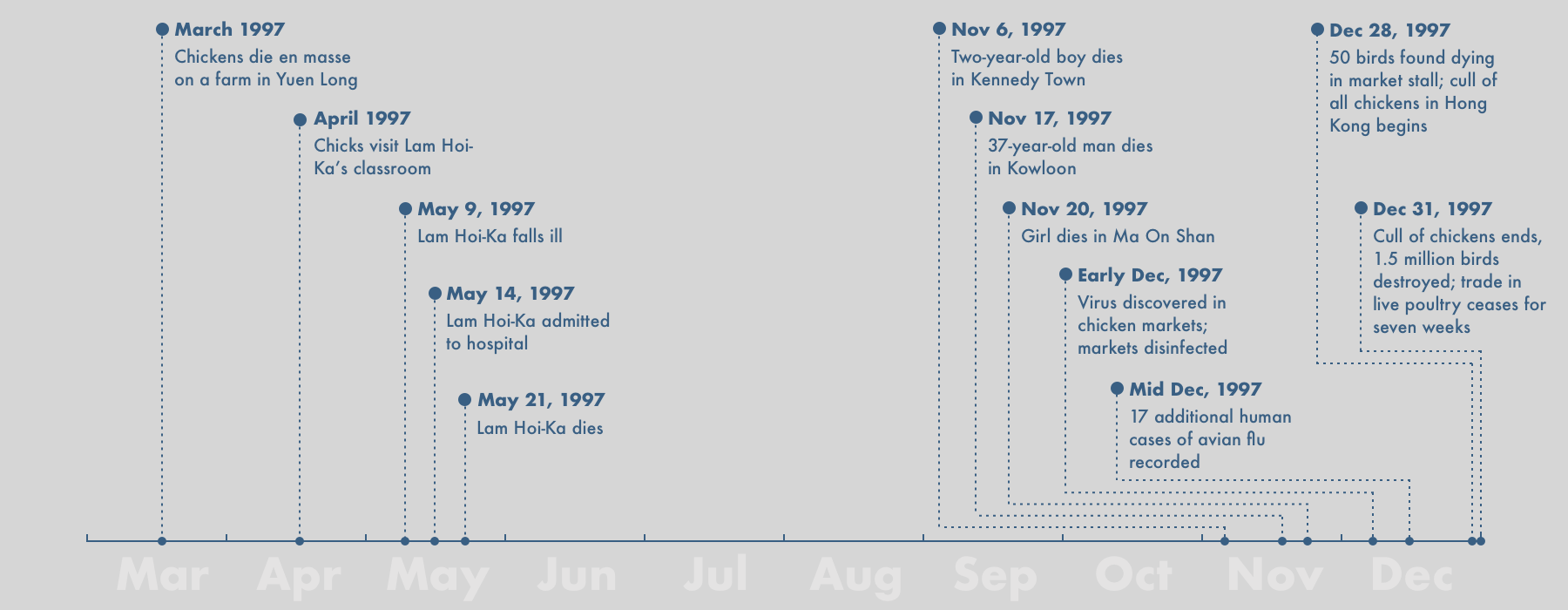

In April 1997, a three-year-old boy from Hong Kong named Lam Hoi-ka arrived at school to find his classroom had been taken over by a gang of unexpected visitors. It was a scene mirrored in primary schools around the world: a chattering of chicks huddled like tiny pom-poms under a heat lamp in a designated nature corner. The children first named, then cradled the birds. Then, one by one, the chicks began to die. Soon, the pen stood empty.

A few days later, on May 9, 1997, Lam Hoi-ka fell sick. His doctor told his parents it was nothing to worry about: a routine fever that would surely pass. After five days, however, it had not. Lam Hoi-ka was admitted to the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Kowloon. There the boy’s symptoms intensified until he became unresponsive. He was given a tube to aid his breathing but a week after he arrived at the hospital, he died. His lungs, liver, and kidneys had failed in quick succession, a result of “disseminated intravascular coagulopathy,” where the body’s blood clots like a river of milk curdling.

That month, Dr. Keiji Fukuda, former chief of epidemiology in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, was in San Francisco when his phone rang. For a moment, Fukuda couldn’t understand why his colleague was telling him about the death of a child halfway around the world. After all, seasonal flu kills hundreds of thousands of people every year. The severity of the situation soon dawned. While he was alive, nurses had taken saliva samples from Lam Hoi-ka’s throat. The tests came back positive for influenza, but negative for all known human strains. This was something new.

Mystified by the initial results, Hong Kong’s chief virologist, Dr. W.L. Lim, forwarded the samples to a slew of laboratories around the world. A group of Dutch scientists were first to identify the strain: a so-called H5 virus, one hitherto only found to infect poultry and wild birds. “No other human being had ever been reported to be infected by an H5 virus,” Fukuda recalls. “My first thought was that this must have been a contamination that had come out of a laboratory, rather than something that had happened out in the wild.”

In fact, this particular strain of bird flu had been ravaging Hong King’s bird population for several months. The first chickens died on a farm near the rural town of Yuen Long. The infection quickly spread to a second and then a third farm, each time with grisly results. One farmer recalls seeing his birds begin to shake as thick saliva dripped from their mouths. The wattles on other birds turned green or black, giving the chickens the appearance of feathered zombies. Some hens started laying eggs that had no shells. Others fell dead on the spot, asphyxiated from blood clots lodged in their windpipes. By the time of Lam Hoi-ka’s death, nearly 7,000 birds had succumbed. It had, as Fukuda put it, happened not in the lab, but out in the wild.

In Hong Kong, Fukuda and his team quickly concluded that virus–now named H5N1–had not been accidentally leaked from a laboratory, but instead represented the first case of an H5 virus transferring from a bird to a human. Panic erupted among the experts. “We had this dogma that there was an extremely high host/species barrier that kept avian influenza viruses from infecting humans and vice versa,” Nancy Cox, director of the Influenza Division at the CDC at the time, told me. “Those ideas had to be peeled off, one by one. This was a new situation.”

Early tests had shown this avian flu virus to be a thousand times more infectious than typical human flu strains. Its mortality rate was around sixty per cent. Robert Webster, author of the Textbook of Influenza, first began studying avian flu when, during a beach walk, he noticed a large number of birds dead along the shoreline and wondered whether there might be a link between the avian flu and the human flu. He described the H5 virus and its cousin, H7 as, simply, “the nasty bastards.”

Fukuda’s team visited Lam Hoi-ka’s school and, on bended knees, swabbed the floor where the doomed chicks had been kept for evidence. But the samples came back clear. “We just could not figure out how that boy got infected,” says Fukuda. They began to frantically collect blood samples from other children in the New Territories–more than 2,000 in total–to find out if Lam Hoi-ka was patient zero in an emerging pandemic. “Some blood tests suggested that maybe some people had previously been infected but it was a tiny handful,” Fukuda said.

One of the nine people found with H5N1 antibodies in their blood was a doctor who had treated Lam Hoi-ka. She later recalled that she had once brushed the boy’s tears away. Fukuda and his team returned to America, hopeful that the danger had passed. It was as if, he later said, the human race had dodged a bullet.

Or had it? In November, Lim sent an email to the CDC. The hospital, he wrote, had evidence of a second infection–a two-year-old boy from Kennedy Town, in the northwest of Hong Kong Island. But this time it spread to other patients. Eleven days later, on November 17, a 37-year-old man from Kowloon fell ill. Then, on November 20, a girl from Ma On Shan. By the end of the year, 18 people in Hong Kong had been infected. Six had died. “When we investigated the first case we were convinced it was an exception,” Fukuda told me. “This time we were growing increasingly terrified that it was going out of control.”

Anticipating the worst, the Hong Kong authorities settled on a biblical course of action in an effort to contain the pandemic: they ordered the culling of every chicken in Hong Kong–more than 1.5 million of them.

Birds have a reassuring presence. The dawn chorus proclaims the fresh promise of the new day. The dove, twig in beak, announced to Noah the end of his watery exile. Ancient mystics claimed to divine clues to the future in the entrails of birds, as if they carried inside their bodies the key to our destiny. The image of the canary in the coalmine, which gave its life to warn us of gaseous danger, remains strong.

At times, however, the image of the benevolent bird has been upturned. Each day, as a punishment from the gods, Prometheus had his liver pecked out by an eagle. In Daphne Du Maurier’s 1952 short story “The Birds,” popularized by Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 film of the same name, the novelist posed the questions: what if the birds turned against us? What if, in fact, the destiny that the birds carried in their bellies was not one of munificence, but of annihilation?

Avian flu, or “fowl plague,” as it was called shortly after its identification in 1878, has not, even in its most recent, Hong Kong varieties, borne out the threat envisioned in these stories. Since 1997, fewer than 500 people have died as a result of avian flu: a fraction of the number that died as a result of the ebola outbreak in 2014, or of the 35,000-or-so people who die each year in the US from seasonal flu (dubbed “influenza” in the 18th century by the Italians, who attributed the disease to the influence of the stars).

Yet H5N1, and its more recent and deadly counterpart, H7N9, remain the subject of keen study in universities and laboratories around the world. The World Health Organization closely monitors new cases of infection, while governments work to broker deals on how to deal with a bird flu pandemic.

We live in a period of what can often feel like unprecedented existential anxiety. The human world has never before experienced such widespread peace and prosperity, yet we’re bombarded with stories from scientists, researchers, politicians, and journalists on the looming crises we face. At times so-called disaster journalism can feel like an extension of apocalypse fiction, those endless films, video games, and novels that rehearse the way in which the world ends. The lines between entertainment and study blur.

At the same time, the political landscape has become ever more chaotic, with countries retreating into isolationist policies that cannot help but undermine international efforts toward collaboration. Then you speak to the experts, the majority of which believe it is not a question of “if” the world will find itself in the grip of a deadly international pandemic, but “when.” The National Academy of Science’s Institute of Medicine now describes a pandemic as not only inevitable, but overdue.

Two decades after Lam Hoi-ka’s death the question of how we will deal with the aftermath and consequences of pandemics can only be robustly answered by examining the systems, the plans, the agreements, the vials of vaccine that are in place today. But they’re not enough, the experts say. “The world is profoundly unprepared to control or manage a major pandemic,” Dr. Irwin Redlener, Director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University, told me. “Appropriate vaccines are not yet available in sufficient quantity to stop a pandemic and the most important innovations in vaccine science are still years away.”

Humanity and the world we inhabit may be facing a bevy of looming disasters, but for Fukuda the question of whether bird flu ranks among them is fully settled. “For the people who work on influenza day and night, the concern around bird flu continues to run extremely deep,” he said. “Some people have tried to make the case that, because H5N1 hasn’t evolved to become more deadly or transmissible, it’s unlikely to happen in the future. But history presents zero guarantees about the future. Why can’t bird flu evolve to become more transmissible, more deadly in coming years? We are not sufficiently prepared.”

The question, then, of what happens next is legitimate–and we do not have to rely on speculation. In almost-living memory, on the other side of The Great War, sits the great plague of 1918, an outbreak that killed at least 50 million people in the space of a few months. The Spanish Flu, as it was deceptively called, had a mortality rate of between two and three per cent. And it, too, started with the birds.

Read the next installment: “Foreshadowing: How avian flu shaped the Great War“

Read the previous installment: “Pandemics: A Reading List“

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. Fowl Plague is a five-part series that explores the history of deadly global pandemics–and asks whether we’re ready to respond to the next one.