On July 7, 1919, lieutenant colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower left Washington, D.C., with a military convoy of 81 vehicles. His destination was San Francisco, and his objective was to test how swiftly the U.S. military could move across the country, and defend it coast to coast.

Disappointingly for Eisenhower, it took his 23 officers and 258 men a full 62 days to cross the continent–a week longer than anticipated. Everything was more difficult than they expected, as they encountered impassable roads, were forced to cut through woods, and had to build or repair bridges along the way. Legend has it that this experience influenced Eisenhower to pass the Highways Act when he became president almost 40 years later.

The need for efficient, statewide defense was what initially led to the gargantuan highways system that has profoundly shaped America’s urban and rural space, and with it the entire continent’s predominant mode of transportation. The Highways Act, a supposed Cold War necessity, cemented the dominance of the private automobile in the U.S. and, in many ways, helped to impose it on most of the world.

Since then, it has become very easy to convince ourselves that owning a car, having access to roads and gasoline, and obeying traffic signals is merely an expression of our evolved technology–something neutral and objective. Things we are accustomed to can feel like the inevitable result of linear, uninterrupted progress; the natural conclusion of continued scientific research.

But owning and driving a modern car, a common practice for a substantial percentage of the planet’s population, is not merely the result of technology. While the gasoline-powered automobile was invented in the mid-1800s, it didn’t start gaining popularity outside of the United States (where the rise of the private automobile was directly linked with Fordism in the 1920s) until after World War II–a century after the technology was developed.

“What we see now as mainstream transport systems and travel patterns is the result of many observed and unobserved processes of the past, including politics,” says Dimitris Milakis, an assistant professor at Delft University of Technology who specializes in emerging mobility concepts.

Urban historian and Princeton professor M. Christine Boyer agrees that policy and politics are what really “determine the infrastructure and the technology on and by which we travel.” Decisions made by politicians guide scientific and technological research and its applications, which then subsequently influence our politics in a dynamic feedback loop. In short, having access to a set of technologies does not mean a society will use or apply them in predetermined ways.

Examples of how politics, technology, and travel interact go as far back as the construction of the vast road network that connected the ancient world to Rome. The creation of that network, which still influences European travel today, was a deeply political choice based on the very real necessities of the empire. Rome had to be safely interlinked to its distant provinces, allow for trade throughout its lands, and be swiftly able to deploy its troops when necessary. It was the first major political entity that could not have existed without its road network.

Similarly, when Blaise Pascal introduced the public horsebus in 1662– effectively creating the world’s first bus service–his innovation didn’t involve inventing something new; instead, it just meant using existing technology in a radically different way. Pascal may not have consciously acted in a political manner, but the resulting invention of mass transportation was undoubtedly political.

Uber has done almost the same thing over the last decade. The company capitalized on existing technology to offer cheap “taxis” at the push of a button. But by convincing politicians that it is foremost a technology firm, Uber has avoided being regulated like a taxi company–undercutting existing taxi companies in the process. It isn’t Uber’s technology that has shaped national transport policy in countless countries–it’s the politics of how the firm behaves.

Throughout history, travel innovations have had to overcome political obstacles, adapt to existing ideologies, and occasionally alter perceptions. For example, despite horseback riding’s being ancient technology even in ancient Greece, the cost of owning and maintaining a horse meant not everyone had access to it. The hippeis, or the minority of men who could afford one, were an integral part of Athens’s early and strictly class-based democracy. It wasn’t until cities chose to make owning a horse cheaper by providing infrastructure that the technology could spread to the masses.

Today, throughout the industrialized world, horses still provide a means of travel for millions of people. Yet in many places, riding a horse is banned on streets. Allowing (or not allowing) beasts of burden on village and metropolitan roads is an obvious political regulation, one that can be argued both for and against from progressive and reactionary viewpoints.

Speaking of horses, how can 2001’s revolutionary Segway, or the hydrogen-powered car, be comparatively less popular than this ancient means of transportation–despite their obvious advantages? The answer is politics: Designing, regulating, and taxing a particular mode of travel can encourage or deter it. Segways cannot be ridden on public roads or pavements in the U.K., for example, while governments haven’t yet provided the fuel infrastructure necessary for hydrogen cars to operate in most of the world.

When it comes time for Elon Musk to break ground on his much-anticipated Hyperloop, he’ll swiftly discover that politics is considerably more of an obstacle to new forms of transport than technology can be. In this case it comes down to land–the real challenge in constructing a high-speed train line is that land is very expensive to buy and build upon over hundreds of miles (or kilometers as it may be, depending on where you live). Politics is what determines how easy it is to use eminent domain for civil projects.

For further evidence of this, think of bicycle lanes and compare the cityscapes which have welcomed them to those that have not. The streets of Copenhagen, where 36 percent of commuters cycle, feel very different than those of Minneapolis, which has a similar population but a commuter cycling rate of just 4.6 percent.

“Look at China and its transit system in Shanghai (even the Bund sightseeing tunnel), or Hong Kong’s new subway system–clean, fast, friendly, efficient, technologically advanced,” says Boyer. Both are systems designed for heavy and affordable use. London’s pioneering Underground, on the other hand, is always at the center of debates regarding fares and ownership, and Moscow is still treating its Metro as both a palace for the people and a bomb shelter.

Los Angeles originally embraced, then dismantled, and has eventually partly re-embraced most of its public transport networks, showing the unresolved battle between mass and individualized transport. Chicago owes its breakneck 19th-century expansion to its status as a major transportation hub at the top. “The flow of goods, people, ideas is what makes a city dynamic, innovative,” says Boyer. “Logistics is one of the greatest planning areas, which impacts the economic stability of every city around the globe.”

Similarly, if and when self-driving cars become available to the masses are not merely technical matters. Perceived or actual fears will have to be alleviated, legislation passed, opposing corporate interests somehow settled, and tricky aspects of human behavior, like the love of driving and speed, dealt with.

Questions about the type of travel needed and how to accommodate it dominate local politics. Is the transportation of tourists more important than everyday commuters in urban spaces? Should more investment go to intercity or intracity transport infrastructure? Should the public or the individual be the focus?

Milakis argues that an equilibrium of sorts has to be achieved in transport systems: “I believe that humanity should offer urban and transport systems that are accessible by all social groups, environmentally sustainable, and economically efficient. This can be achieved by a combination of individual and collective modes of transport.”

Boyer points out, “Individual transportation, or automobiles, is the greatest polluter on earth. To tackle global warming, we need public transportation–good, reliable, technologically up-to-date public transportation.”

But making public transport available to everyone, if only to help safeguard the quality of our environment, has been a constant struggle. That’s because seemingly technological problems like making more travel options, or achieving zero carbon emissions, are actually primarily political problems.

Deciding whether public transportation is required, or if environmentally friendlier tech should to be developed, ultimately comes down to politics and the people. It is us who will choose–democratically or through protest–whether we want to travel freely or stop at militarized borders, whether we want better public transportation or are fine with automobiles, traffic, and all the pollution that comes with them.

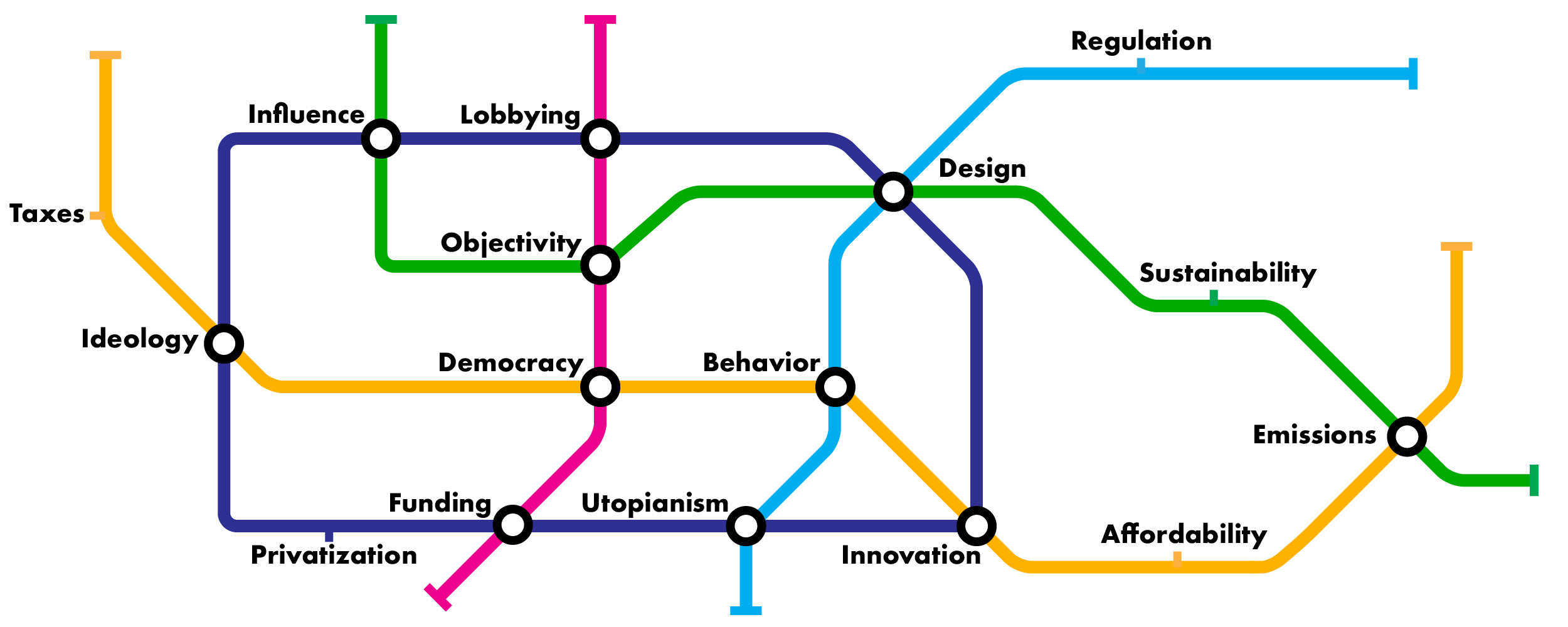

Technology alone will not provide us with miracle solutions. If we really want to achieve sustainable, efficient, fair, safe, and environmentally sensible ways of moving both things and ourselves around, we have to start thinking politically. We even have to question prevalent tendencies such as the privatization of mass transport, consider whether moving to hybrid private cars is wise, or discuss the moral dilemmas that arise in the design of self-driving vehicles.

In stark contrast to the contemporary techno-utopianism that believes Silicon Valley can solve everything, from pollution and congestion to driver safety and trip pleasure, the multi-faceted evolution of human society is neither a technical nor a technological matter.

It is deeply political, hotly contested, and at the center of uncountable struggles.

This post is part of How We Get To Next’s Going Places month, profiling solutions to modern transport problems over the course of February 2017. If you liked this story, please click on the heart below to recommend it to your friends.