On the evening of September 24, 2014, Tim Keane marveled at the calm weather from the deck of the Nunavik. The ship, owned by the Canadian firm Fednav, was carrying a cargo of nickel concentrate from the Canadian Royalties mine in Northern Quebec to the port of Dalian in northern China. It was the first time the company had sent one of its ships through the Northwest Passage, an occasion considered sufficiently important for Keane, its senior manager for Arctic operations, to join the crew’s voyage.

“We took advantage of the fair weather to dine al fresco tonight,” he wrote in his log as the ship reached Beechey Island. “An elegant table (built by the deck crew) was set by the chief cook and steward–kraft paper instead of linen, held in place by duct tape. Plenty of food, good company, and conversation around the BBQ built onboard by the engineering staff.”

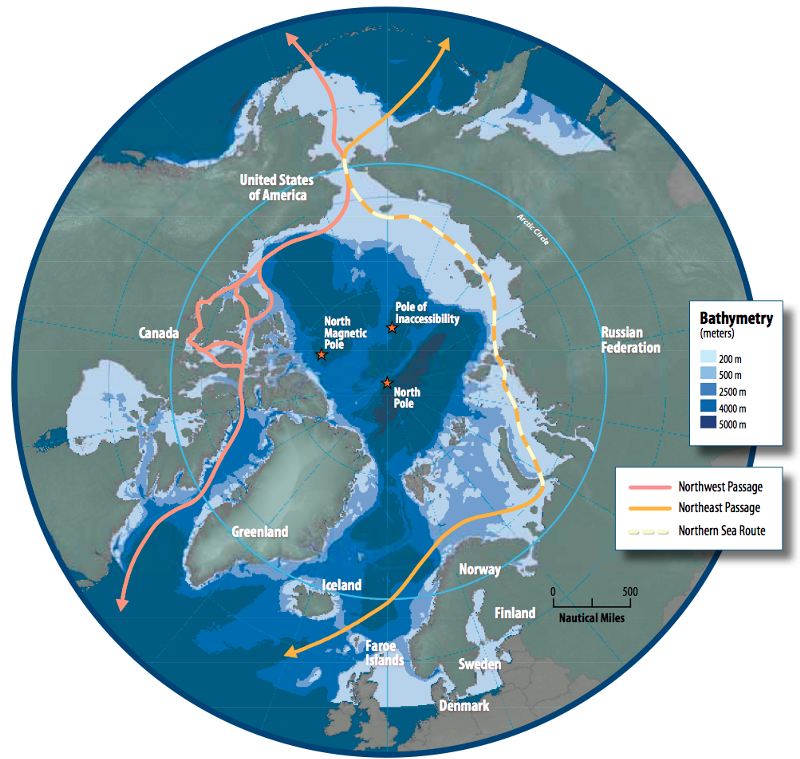

Beechey Island, as Keane also noted in his log, was the last resting place of two of the crew from the ill-fated Franklin Expedition in 1845. John Franklin was just one of many European explorers who tried and failed to find a path from the Atlantic to the Pacific through the Canadian Arctic. Very few returned home from that voyage, whose potential rewards were huge–a vessel traveling from Hamburg to Shanghai through the Northwest Passage would cut 2,300 miles off its journey, compared to traveling via the Suez Canal, and approximately 5,200 miles if it were to sail through the Panama Canal.

Traditionally, what prevented ships from sailing this route was the harsh conditions that beset the region in its winter months. This far north of the Arctic Circle, pack ice has been known to trap vessels for months at a time. These were the conditions that killed Franklin and his men, and forced famed polar explorer Roald Amundsen and his crew to spend two consecutive winters on King William Island before they finally conquered the Passage on the Gjøa in 1905.

Over the past decade, however, global warming has begun to diminish the dangers of sea ice. In 2007, the European Space Agency announced that the Arctic ice cap had contracted to its smallest radius in history, therefore making the Northwest Passage fully navigable to shipping. Six years later, in 2013, a cargo vessel sent through its waters by Nordic Bulk Carriers became the first to demonstrate the route’s practicality; in 2014, Fednav would confirm this with the Nunavik.

Since then, there has been a surge in investment and territorial claims along the rim of the Arctic Circle in anticipation of the region’s opening to commerce. It is a fever that has seen Chinese billionaires and German consortiums fighting to acquire obscure Icelandic inlets; a signing ceremony for an agreement between a Greenlandic mining company and its state-owned South Korean contemporary considered important enough for the latter’s president to attend; and the townspeople of Eastport, Maine, propose that a shipment of pregnant cows act as a sign of the port’s bright future at the terminus of a new trade route. The stage is being set for the emergence of the first new sea lane in centuries.

A safe trip through the Northwest Passage hinges upon an appreciation of its inherent unpredictability. Climate change may have made the journey easier, but it hasn’t wholly eliminated the risks. “Nobody should ever go into the Arctic on the presumption, based on the media reports of less ice and everything else, that there is still no dangerous ice,” says Keane. “There is, and it can be present in very, very small quantities, but it doesn’t take much ice to really ruin your day if you don’t approach it carefully.”

Aside from the threat of rogue icebergs tearing through the sides of vessels, the waters along the route can also prove dangerously shallow. Off the Beaufort Sea, the geographic end point of the route and where the thickest ice floes have historically been encountered, pingos–immense frost heaves fed by local river deltas–lurk menacingly beneath the waves. In September, however, the warmest time of year, the straits become navigable to large ice-strengthened vessels, and it was with this knowledge that Fednav took a calculated risk and dispatched the Nunavik.

The danger of the Northwest Passage is a theme Keane returned to time and again in his log. At one point, he noted that the power plant in the belly of the Nunavik could deliver some 30,000 horsepower, “enough to ease the ship through 1.5m of solid ice,” if need be. On the fourth day of the trip, bottle-nosed whales swam the length of the ship while dozens of bergs were plotted on the ship’s radar. At night, watchkeepers were on alert to spot the heaviest chunks. “The new ice crystallising on the surface gives the sea a satiny, almost greasy look,” wrote Keane. “It damps the swell and makes the older, heavier pieces stand out even more. The ship’s radar picks up a bit more clutter, but the heavier ice is easy to spot with the naked eye.”

On the tenth day of the voyage, Keane disembarked at Sachs Harbour, on the southwest coast of Banks Island, leaving the ship to continue its journey to China. Despite the voyage turning out to be largely uneventful, Keane is unconvinced that the company will be mounting similar expeditions through the Northwest Passage anytime soon. Neither, he believes, will other Arctic shipping companies. “There’s always going to be some risk involved, and so for those reasons we’ve said for some time that we see the North more as a destination than a transit route,” says Keane. “It will never make sense to take extra time to go through the Northwest Passage. And if it did, what would be the attraction?”

Container ships tend to sail according to the “just-in-time” system, wherein goods are transported according to precise schedules. Under this mode of operation delay is anathema, and with sea ice still predicted to litter the Northwest Passage up to the 2050s, it wouldn’t make sense for large cargo vessels of this type to transit the route until then. Bulk cargo vessels, which do not rely on these tight schedules, might fare a little better. Nevertheless, the icy conditions that are predicted to endure across the region for the next decade would predicate the use of ice-strengthened ships like the Nunavik, for which the acquisition costs may prove prohibitive.

Even so, a “never say die” attitude toward opening the Northwest Passage continues to persist, along the broad lines that the permanent retreat of the Arctic ice cap is a lucrative, if sad, inevitability. In 2008, Denmark, Norway, Russia, the United States, and Canada collectively issued the Ilulissat Declaration, in which nations pledged to resolve any lingering territorial dispute they had with one another in an orderly fashion. And although Ottawa and Washington continue to disagree on whether the Northwest Passage is international waters–the Canadian government continues to say it’s not–there is increasing pressure on both sides to come to an amicable agreement on the matter in the interest of seizing on the broader gains an open Arctic offers.

While laying the ground for a diplomatic framework of greater international cooperation continues, research institutions have been tasked with actively preparing shipping companies, rescue agencies, and local communities for that future. For scientists at the National Research Council (NRC) in Canada, it’s a scenario for which they count upon some six decades of experience.

“If we look at what could happen going forward, we could see an increase in the mobility of extreme ice features, such as multi-year ice that traditionally has been land-fast,” explains Anne Barker, the head of the NRC’s Arctic research program. “[The ice] may now break off and enter, perhaps, some of our marine corridors.”

Barker has already begun to observe changes in shipping patterns through the Canadian Arctic. Whereas for many years vessels had primarily ventured north to isolated hamlets like Sachs Harbour and Cambridge Bay on resupply missions, or to mining installations eager to dispatch their coal and oil southward, the fastest growing commodity in the Canadian Arctic is, currently, people. The arrival of cruise ships to these waters carries its own special safety considerations. “We’re seeing an increase in [the use] of some of our tools, things like iceberg drift models and databases that we maintain federally,” says Barker. “They’re not new tools, but there may be an increased need for them depending on how things change as we move forward.”

Unless the pace of warming dramatically accelerates, these tools may not be enough to convince shipping companies to avoid the Panama or Suez Canals and send cargo through the Northwest Passage. Still, Wolfgang Koch of the Fraunhofer Institute in Munich believes maximum surety of navigability is eminently achievable with the right mindset.

A theoretical physicist by training, Koch is a member of the PASSAGES project, an attempt by German and Canadian scientists to unite all the disparate sensor data available on ice flows in the Northwest Passage into one overarching navigation control system. The goal is to make the charting of obstacles in these waters a fine art, thereby making it easier to insure ships and bestow the necessary confidence for companies to send container vessels through the Canadian Arctic.

“As a consequence of global warming and monitoring systems, the natural resources of the Arctic can be explored more profitably,” he says. Although the project is in its early stages, Koch and his colleagues have already designed a specific architecture for the underlying system, as well as conducted a risk reduction study in conjunction with their Canadian counterparts.

“Quite evidently, [opening] the Northwest Passage in the Arctic would have a dramatic economic and political impact if it could be passed regularly, safely, and securely with calculable risk,” says Koch. “Since global warming seems inevitable, whatever its reasons or proper countermeasures are, let us make the best of it at least wherever we can.”

Walking back to his boat, moored along the quay in New York, Dario Schwörer is feeling a little disoriented. A former mountain guide turned roaming climatologist, Schwörer has spent the past 15 years sailing his 50-foot sloop, the Pachamama, on a sponsored voyage around the world with his wife, Sabine, and their five small children. As a result, he is not accustomed to American traffic habits. “Everybody’s driving cars here,” he says, a little breathless. “All I want to do is walk.”

The family’s goal has been to highlight the impact of climate change by climbing the highest mountain on each continent without relying on fossil fuels. Last year, after having spent the summer on the Alaskan coast and well aware of the conditions, Schwörer decided to travel the Northwest Passage from west to east. It was his third attempt, and the first successful transit of the Fury and Hecla Strait in a sailboat.

“This summer, it was really open water between Cape Barrow and the Fury and Hecla Strait,” Schwörer recalls. Not, of course, that the Pachamama’s journey had been an easy one. The autopilot had stopped before the Schwörers had even left Nome, Alaska, exposing them to fierce gales and freezing temperatures as they sailed through the Passage. One afternoon, a hungry polar bear decided to make a threatening appearance just a few dozen feet (some 10 meters) from the boat, before swimming on in search of new sea ice.

Schwörer and his family had not intended to set records on their trip. They had, in fact, sought to visit and learn from the Inuit communities scattered along the shorelines of the Northwest Passage, villages and hamlets that they soon discovered to be in crisis due to climate change. “We’re erasing their existence, you know?” says Schwörer. “In some communities, they [the villagers] told us that the suicide rate is already up to 25 percent.”

Survival in the Canadian Arctic has always been a precarious affair for the Inuit. “Life is so with us that we are never surprised when we hear that someone has starved to death,” a Netsilik elder named Quqortingneq told Danish anthropologist Knud Rasmussen in the 1920s. “It sometimes happens to the best of us.”

Despite the arrival of modern technology and the means to supply communities with aircraft and icebreakers, the daily lives of many Inuit continue to depend on hunting seals and roaming caribou. As the winters contract, however, the algae that grows on the underside of sea ice threatens to disappear, taking the whole food chain along with it. Caribou and seal populations have already nosedived. Although the precise cause remains unclear, Canadian wildlife biologists suspect that poor environmental conditions are reducing pregnancy rates and calf survivability.

“Inuit have been able to work with, and sustain ourselves within, this harsh environment,” says Duane Smith, chair of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation and a leading advocate for Inuit interests in the region. In addition to basic food security, Smith perceives the unpredictability of local ice conditions as the main threat to local communities. As the sea ice has begun to diminish in thickness, hunting has become more difficult. Inuit used to visiting other villages via snowmobile have found it no longer possible. Many have fallen through the ice trying to do both.

This level of ongoing plight, combined with the region’s legacy of economic neglect, has led some Inuit representatives to question the priorities of the international environmentalist movement. “Please stop using polar bears as the icon of climate change,” said Okalik Eegeesiak, the leader of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, in March of last year. In an interview with The Observer in August, Eeegeesiak made it plain that the arrival of shipping, in this case the many thousands of cruise passengers who have started to descend upon the region in the summer months, could have a devastating impact upon both the communities and the wilderness that surrounds them. “These places lack the infrastructure and the training to deal with the incredible numbers of people that will start arriving on these boats,” she told the paper.

That isn’t to say that every Inuit leader believes the gradual opening of the Northwest Passage is all bad. Smith, for one, believes that opportunities could emerge for local communities if new arrivals adopt the right approach: “Inuit want to see controlled development that ensures benefits and services are enhanced within [their] communities, while trying to minimize to the extent possible any negative effects that might be had on the environment and the ecosystems we depend on for our nutrition and cultural sustainability.”

Indeed, there are reasons to think that increased commercial shipping through the Northwest Passage may well have to abide by uncommonly strict environmental regulations. In January, the International Maritime Organization’s Polar Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters–better known as the “Polar Code”–came into force, setting tougher limits on the structural standards of vessels and prohibiting the discharge of oil and toxic substances into Arctic waters. A joint announcement by the U.S. and Canadian governments in the same month also pointed toward the banning of heavy fuel oil discharges by ships in the region, an important step considering the documented hazard it presents to birds and mammals. Absent the infrastructure or sea-borne assets that would allow a quick response, the Inuit would likely be the first responders to a major spill, as well as among the first to be hit by its effects.

While developments like these are promising, Smith believes that the effects of climate change are best observed from within Inuit communities, rather than on the water. Moreover, those communities should be viewed not with pity, but with a greater understanding of the significant hardships they continue to face as a result of climate change. “Visitors should realize the Inuit are constantly adapting and are doing so at a much more rapid pace,” he says.

However, as communities in the far north cope with the coming changes, one thing is for certain: the environment that they have known for hundreds of years is beginning to alter, in many ways irrevocably. It was a fact brought suddenly home to Schwörer in a conversation he had with an Inuit teenager, midway through his voyage. “He really opened his heart and told me about the beauty [of the land], and the stories of his father and grandfather,” in tales that, Schwörer says, the young man glimpsed from the Arctic of his early childhood.

“There was so much silence, and in this silence, there was so much wisdom. And now, you have so much noise.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Going Places section, which looks at the impact of transportation technology on the modern world. Click the logo to read more.