Read the next installment: “Architects of the Future”

Read the previous installment: “Fact, Fiction, and the Future“

In 1941, Walt Disney’s problems were piling up. His third animated film, Fantasia, was meant to “change the history of motion pictures”–but ended up nearly bankrupting the studio. The film came with a revolutionary surround-sound system–”Fantasound”–that needed to be installed in every theater it played in. But the film didn’t make it to many theaters: the outbreak of war in Europe prevented its release in territories that ordinarily would have provided half its income.

The studio’s previous film, Pinocchio, had also lost money, and growing discontent among animators added to Disney’s woes. His lack of empathy didn’t help: “If you’re not progressing as you should,” he told them, “instead of grumbling and growling, do something about it.” The resulting animators’ strike lasted five weeks.

But the war would also offer Disney a lifeline. The U.S. government, recognizing the value of the studio’s emotive visual storytelling techniques, contracted Disney to produce 32 animated shorts. The commissioned films were a mix of education and propaganda, and it was the latter to which the full weight of the creative studio of animators, artists, directors, and writers would be employed. They took animation beyond pure entertainment, using it as a medium to influence and persuade.

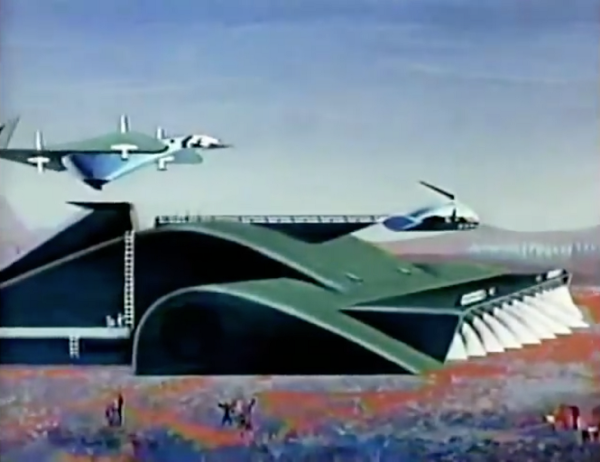

Walt Disney was a pioneer throughout his career, looking to the future in both his medium and through the visions his artists created. But it was this wartime opportunity that brought Disney’s role as a futurist into the public eye, using animation to show concepts like long-range bombers, journeys to Mars, and autonomous vehicles. These films were popular entertainment, but they also worked to sell Disney’s vision of the future to the American public.

Disney wasn’t the first to animate the future. Decades before The Jetsons premiered in 1962, speculation about our future lives was a fertile source for visual gags. Hollywood animators followed in the footsteps of 19th-century satirical cartoonists, lampooning contemporary obsessions with gadgets and technology.

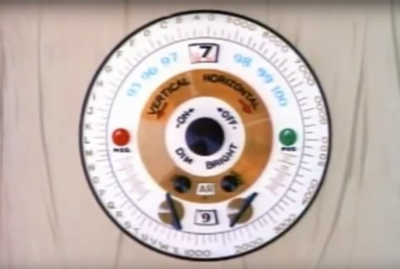

Tex Avery, the animation director who helped found Looney Tunes, created a series of films satirizing technology, with titles like “The House of Tomorrow” and “The Farm of Tomorrow.” Running from 1949 to 1954, they mixed quick-fire visual gags with screwball voiceovers playing up to attitudes of the time. The three-screened television in “The T.V. of Tomorrow” has one for each family member: a cowboy show for the “kiddies,” models in bathing suits for the “tired businessman” father, and a baking show for “the housewife.” Add a few female driver and mother-in-law jokes, and you get a feel for the level of acceptable sexism at the time.

Among the spoofs you can see a few interesting futuristic concepts: a self-building prefabricated home, a live telecast from Mars, genetic modification, and virtual fishing on a TV set (a rare prediction that comes close to anticipating video games). There’s even a user interface joke we’d find relatable today: “Remember those umpteen billion control knobs? Tomorrow’s set, one simple knob”–and then the reveal, a spinning dial with hundreds of settings.

While Tex Avery’s future was played for laughs, Chuck Jones, the director of many classic Bugs Bunny and Road Runner shorts, used animation to show Americans a better future for healthcare. In 1948, Britain had introduced the National Health Service, but in the U.S., the American Medical Association was fighting President Truman’s attempt to push through a national health insurance program.

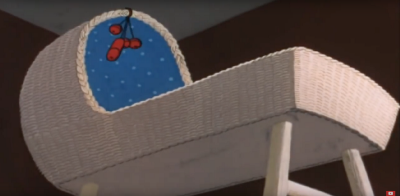

To educate Americans about the benefits of the proposed system, the government commissioned Warner Bros. and Chuck Jones to make “So Much for So Little” in 1949. The possibilities shown in the 10-minute short weren’t as flashy as robotic tele-doctors or bloodless surgery with atomic lasers. It was a more complex sell–the creation of a new system, with potential benefits for society as a whole.

“So Much for So Little” follows the life of a baby, John E. Jones, as he grows up, eventually rewinding back to infancy to remind the viewer that if baby John is to survive, he’ll need proper healthcare. The film won an Academy Award in 1950 for Best Documentary Short Subject.

In 1946, Disney made their own public-health film, “The Story of Menstruation.” It was famous for its pioneering onscreen use of the word “vagina.” But it was during the war that they honed disseminating complex information to the general public through animated entertainment.

As part of their government contract, Disney produced patriotic propaganda films aimed at getting Americans behind the war effort. “Der Fuehrer’s Face” pushed war bonds; in “The New Spirit,” Donald Duck encouraged tax-paying. “Education for Death” took a more serious tone, depicting a young boy indoctrinated into Nazi ideology, with “no seed of laughter, hope, tolerance, or mercy.”

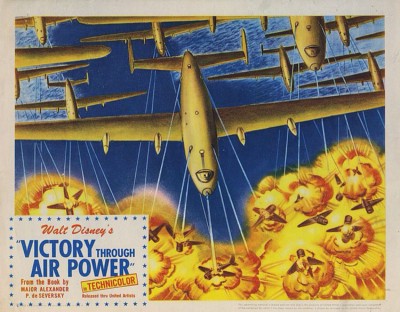

In 1942, Walt Disney read Alexander P. de Seversky’s Victory Through Air Power, which made a case for the use of long-range bombers by American forces. Until this point, U.S. war preparations had focused on things like battleship production over manufacturing aircraft. Convinced by the core message of the book, Disney funded the production of a film version himself, rushing it into production with Percival Pierce, the story director of Bambi.

The film mixes a history of flight with thrilling animated dog fights, as Seversky himself explains his theory. The message is hammered home–without much subtlety–with an image of an American eagle destroying an Axis octopus and the dark shadow it had spread across the globe. Victory Through Air Power was given a theatrical release by United Artists. But it was also seen by Winston Churchill, who then organized a screening for Franklin D. Roosevelt, who in turn organized a screening for his Joint Chiefs of Staff.

After the war, Disney would continue to bring the creative weight of his animation studio to introduce, educate, and sell complex ideas to the public. And soon, he would be able to get his ideas about the future directly into American living rooms.

Most film studios saw the rise of television as a threat–but Walt Disney saw it as an opportunity. In 1954, Disney was trying to build his first theme park, Disneyland, and he needed a large amount of capital. Television was the answer: the ABC network offered a partnership in which they’d pay for the park while Disney provided a weekly hour-long anthology TV program. ABC got the coveted Disney brand; Disney got access to a new medium to promote his ideas.

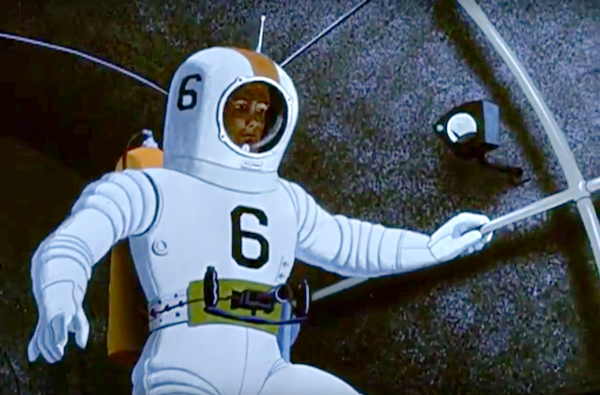

Themed around the four areas of Disneyland, the program mixed history, nature, fairy tales, and stories about science and the near future, known as “Tomorrowland.” The first season featured “Man in Space,” a “science factual” pitch from ex-Nazi rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, two years before the launch of Sputnik. It was followed later that year by “Man and the Moon,” a detailed explanation of how cargo rockets would supply an orbiting space station, the launch pad for the 10-day journey to the moon.

“Man in Space” was watched by an estimated 42 million people, including members of the American and Soviet governments. A prominent Soviet space official wrote to the president of the International Astronautical Federation to request a copy of the film. “If the Disney Studios supplies us with one copy of this film on whatever terms it may put,” he wrote, “it will make considerably for the cause of promoting our contact.”

Further seasons reached deeper into the solar system. “Mars and Beyond” offered a look at how to get to Mars via atomic spaceship. “Our Friend the Atom” delivered a layman’s guide to the atom, exploring the idea of atomic energy while acknowledging the potential destructive force of unleashing the atomic “genie.”

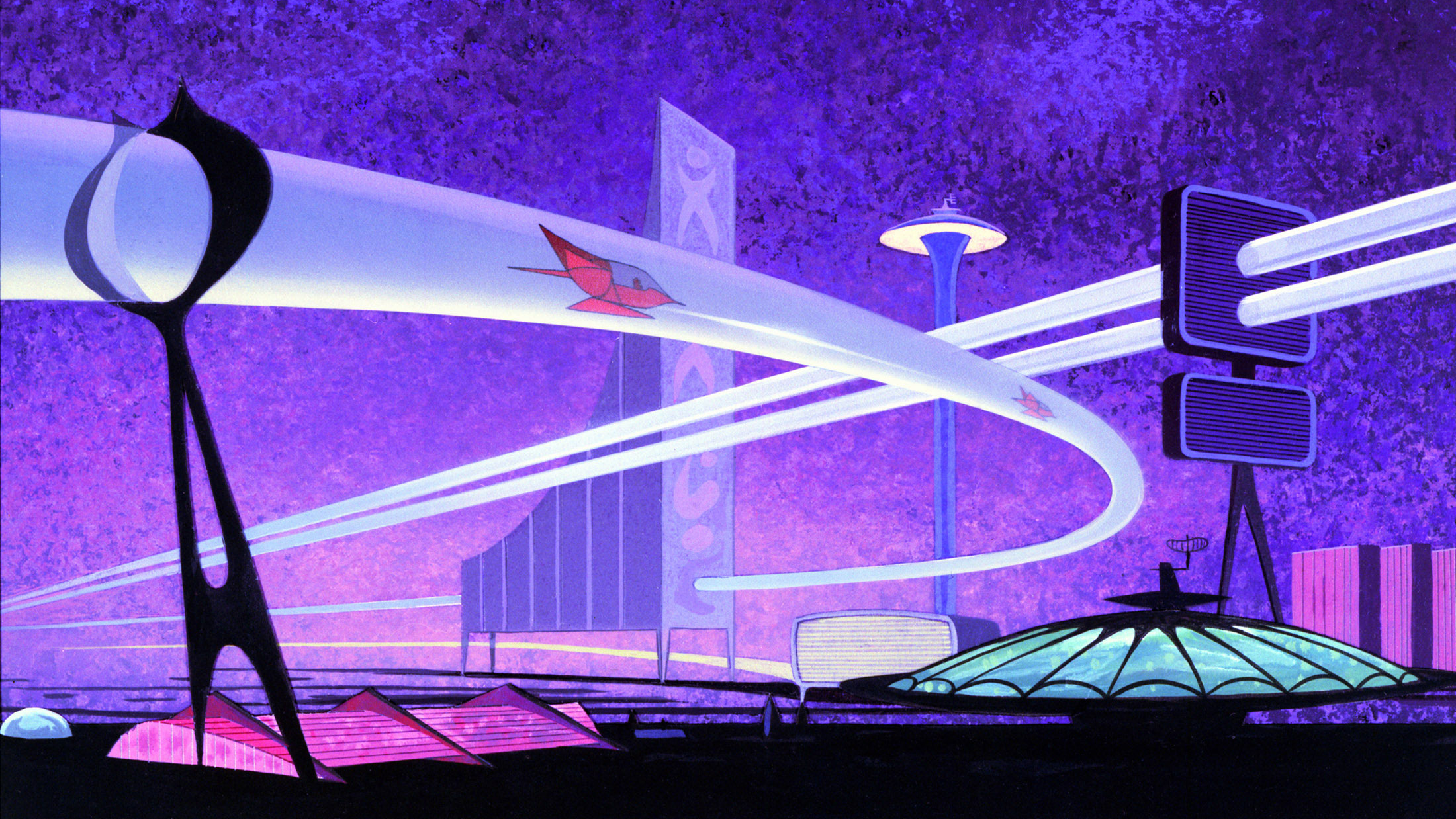

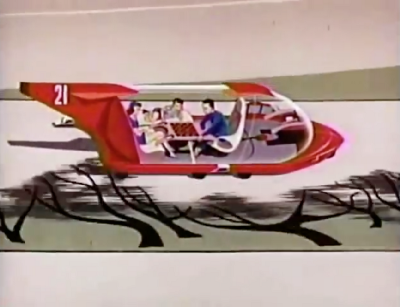

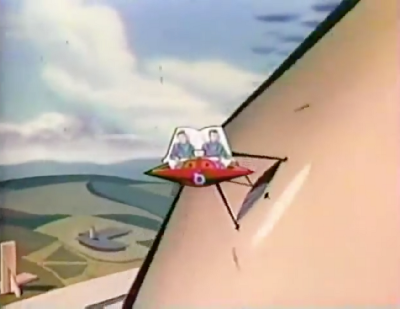

A 1958 episode of Walt Disney’s Disneyland, “Magic Highway U.S.A.,” covered the broad evolution and history of American motoring. But it was the last nine minutes, an animated segment called ” The Road Ahead,” where Disney’s Imagineers were let loose, creating “a realistic look at the road ahead and what tomorrow’s motorist can expect in years to come.”

President Eisenhower was advocating for stronger transport links across the U.S., especially to move troops and supplies in the event of an attack, a tangible fear in the developing Cold War. In 1956, he signed the Federal Aid Highway Act into law: 41,000 miles of new roads would be built, the largest public works project in American history at that point.

Partly funded by the Portland Cement Association, “Magic Highway U.S.A.” was Disney’s attempt to try to shape the vision of these future roads. To bring his ideas to life, Disney used some of his animation studio’s finest talent. It was directed by Ward Kimball, a Disney veteran and member of the core group of animators known affectionately as “Disney’s Nine Old Men.”

Kimball had previously worked on Snow White, Dumbo, and designed Jiminy Cricket for Pinocchio. His animation team included Charlie Downs and Jacques Rupp, who worked on the spaghetti sequence from Lady and the Tramp. The narrator of the sequence was Marvin Miller, no stranger to the future, as the voice of Robbie the Robot in 1956’s Forbidden Planet.

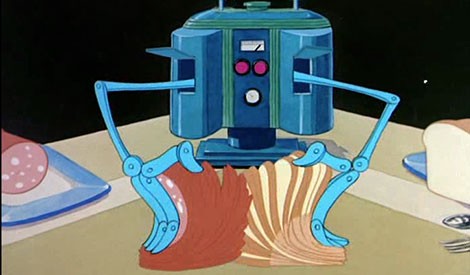

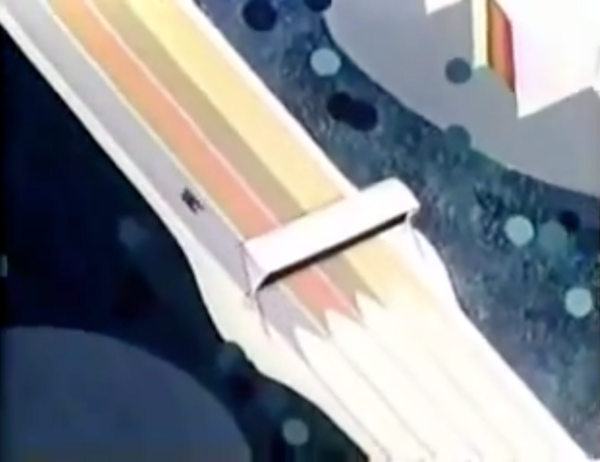

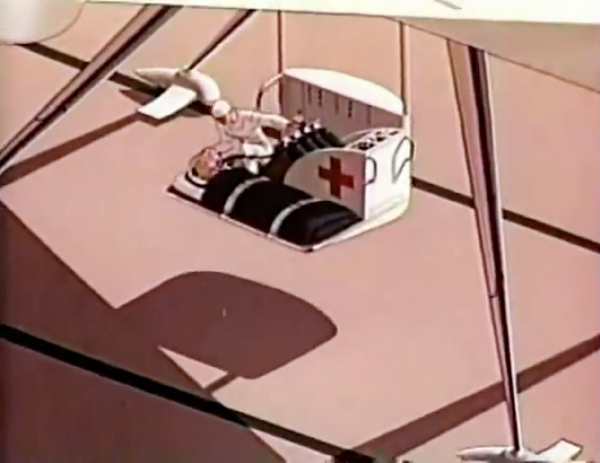

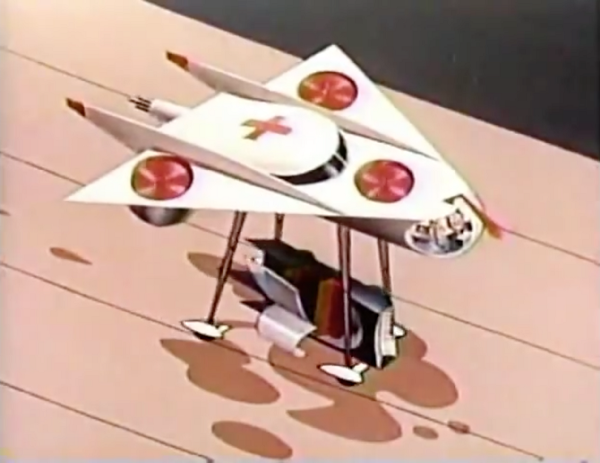

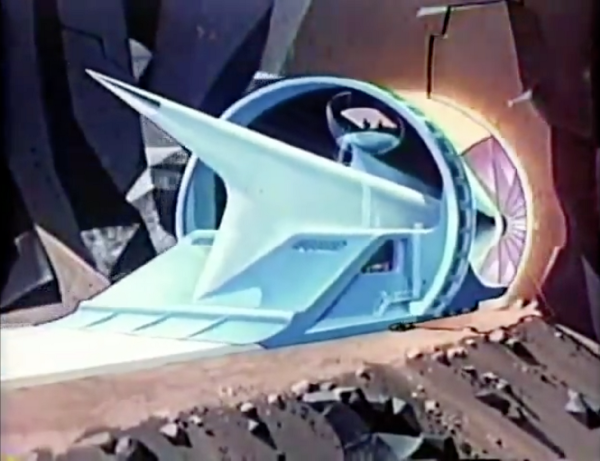

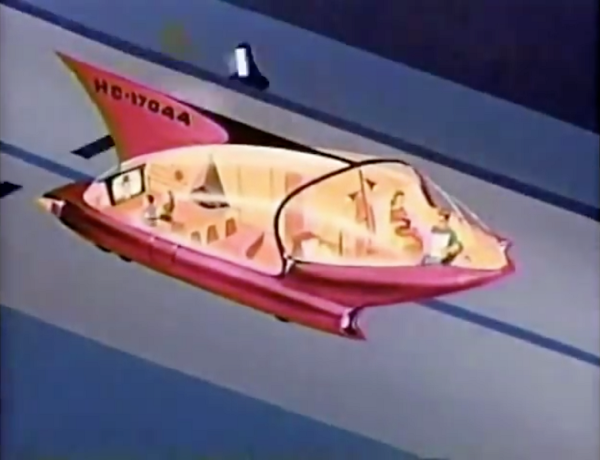

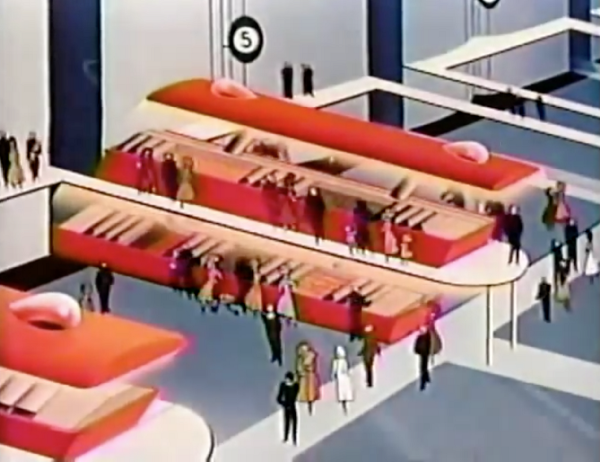

The film itself uses the full might of the studio’s storytelling skills: perfectly balanced compositions, stylistic design, and finely-tuned color. Multi-colored highway lanes help steer traffic, and heated roads keep them clear of treacherous ice and snow. Windshields double as radar screens to enable driving through dense fog, while dashboard displays show travel conditions and suggest safe speeds. When accidents do occur, airborne emergency vehicles fly in to save lives–and clear the roads quickly to ensure traffic starts moving again.

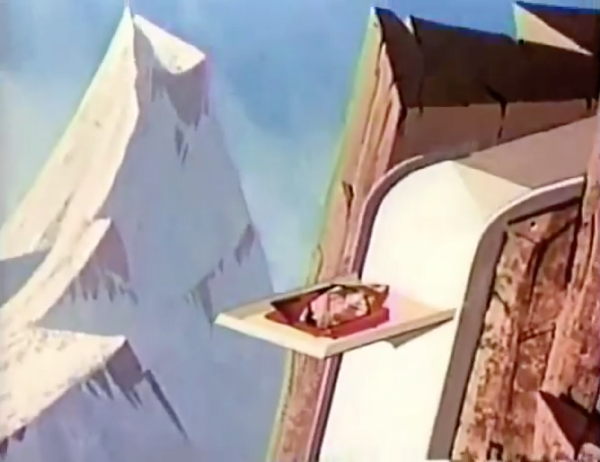

Tomorrow’s roads are to be built with giant devices that lay out pavement like a red carpet; bridge-building machines cross valleys and rivers. Obstacles like mountains are easily navigated using our old friend atomic power to melt through the rock. Arthur Radebaugh depicted similar ideas in “Closer Than We Think,” including a version of “the new jungle-smashing LeTourneau “‘tree crusher”‘ and an atomic reactor that would “fuse the earth into a rock-hard, glass-smoothed surface.”

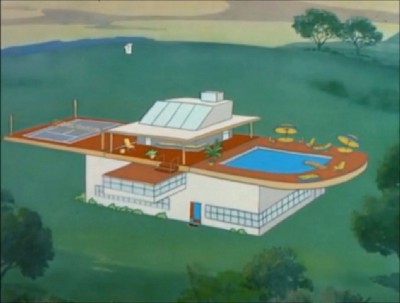

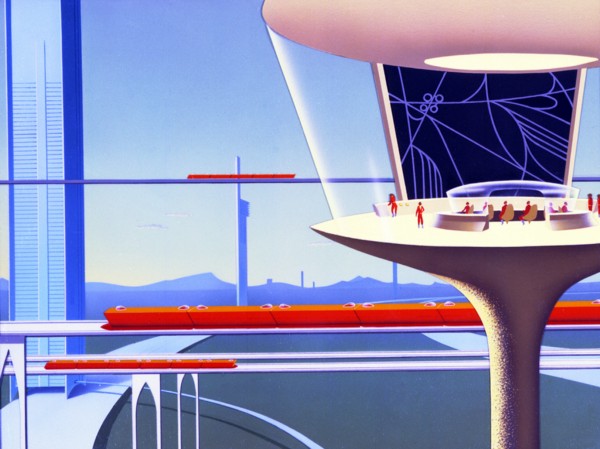

As the highways of the future make transport easier, the shape of cities change as well. Commuters travel into the city from their Monsanto Houses of the Future along suspended roads; self-driving vehicles separate in two, taking Father to work and parking directly by his office on the 30th floor, while Mother and Son go shopping along moving pedestrian walkways.

Automation leaves more room for leisure time in your amphibious home on wheels. You use punch cards to program a destination, and if mountains are in your way (presumably the atomic tunneling machine hasn’t made it to your area), vehicle-carrying elevators will take you straight up the cliff-face to continue your journey.

The complex logistics of distribution are reinvented as truck trains transport goods. Individual trucks separate at junctions to fill ships, deliver goods straight to the consumer, and even to load up cargo rockets on their launch pads.

Projecting further ahead, the car evolves, running on jet fuel and then atomic power; eventually, our floating cars will be powered by the sun. Air-conditioned tubes flow across the desert and connect domed undersea cities. Eventually the highway is superseded by vehicles traveling in new dimensions: sideways up buildings, or using gyroscopes to travel on top of or underneath elevated tubular roads.

“The Road Ahead” presented a dizzying array of concepts. But all that speculation tied into a core message: as Disney himself put it, the segment was a “Magic carpet to new hopes, new dreams, and a better way of life for the future.”

Disney’s enthusiasm and resources meant that some of these “new hopes and new dreams” could manifest themselves in reality. The “Monsanto House of the Future”–as seen in “Magic Highway U.S.A.”–was a real fiberglass and plastic structure in Disneyland’s Tomorrowland, a collaboration between Monsanto’s plastics division and architects and engineers from MIT.

The visions of the future in Disney’s first television show feel less like whimsical speculation and more like part of a millionaire industrialist’s grand plan for the world. As an expert visual storyteller, Disney was perfectly poised to use the medium to achieve maximum impact. He was moving towards his ultimate dream: to build the city of the future, the “Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow,” or EPCOT, a utopian example of a better way to live for the rest of the world.

Was Disney’s futurism as high-minded as this–or just the playful sandbox of a man with near-bottomless funds? It’s difficult to measure the influence of Disney’s futuristic visions beyond pure entertainment value. Perhaps “Victory Through Air Power” influenced the course of the war; perhaps “Man in Space” helped to sell space exploration to the public.

It did inspire at least one member of its 42-million-person audience. In 1955, 13-year-old Stephen Bales sat down to watch “Man and the Moon” in his small rural farming community of Fremont, Iowa. “This show, probably more than anything else, influenced me to study aerospace engineering,” he would later say. In July of 1969, Bales was sitting in mission control in Houston as the guidance officer for the Apollo 11 moon landing. He said of the experience, “It was the Walt Disney cartoon come to life.”

Read the next installment: “Architects of the Future”

Read the previous installment: “Fact, Fiction, and the Future“

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. A Visual History of the Future is a five-part series on the way artists’ visions of the future shaped the world we now know.