Speaking to LIFE magazine in 1966, textile designer Julian Tomchin explained that paper dresses were, of course, the future. Cheap and disposable, paper clothing enabled by new materials technology would likely be sold in huge rolls just like sandwich bags. “After all, who is going to do laundry in space?” he asked.

The Scott Paper Company had already released the first paper dress of wood pulp and synthetic fibers as a promotional item earlier that March, the idea itself borrowed from the new paper gowns being used in hospitals as a hygienically disposable alternative to the high cost of laundering fabric.

The throwaway textiles became an instant hit–a brightly printed embodiment of the space age–as paper fashions for both men and women rapidly grew in popularity. A zest for skimpy hemlines (that even the likely risk of tearing couldn’t shake) and an eye toward an intergalactic future made expectations for the inexpensive and colorfully carefree garments beyond sky high. Wastebasket Boutique, the aptly named division of U.S. producer Mars Manufacturing, sold up to 100,000 dresses weekly at the height of the trend. The company’s vice president, Ronald Bard, gave his own confident prediction in that 1966 LIFE article: “Five years from now, 75 percent of the nation will be wearing disposable clothing.”

In fact, by the time man stepped on the Moon three years later, the fad was all but finished. With shortcomings including a flame-resistant coating that rinsed off in the rain, the flimsy garments soon lost out to more durable synthetic fabrics, which continue to drive fashion today.

Often, though, it’s this precise spirit of an age that raises designers’ expectations. Fashion will make use of any new material that becomes available, and designers have always looked outward to wider cultural aspirations and advancements in textiles or manufacturing for that one missing innovation that might initiate a lasting shift–not only in how we dress, but also how we live.

Feeding this ambition is a very visceral response that can inspire the design process. “Some people say they start with the silhouette or with a concept, but so many designers say it really begins with the material,” said fashion and textile historian Nancy Deihl, who is the director of Costume Studies at New York University. “Novelty is what fashion is all about, and so anything new is just irresistible. It’s almost a tangible response–this idea that if something’s new, you can grab it and make something out of it.”

It’s an instinct we can see in the origins of modern fashion, a period that Deihl and adjunct professor Daniel James Cole identify in their book, The History of Modern Fashion, as beginning in the 1850s. This decade is the right place to start, said Deihl, because of its clear alignment between a contemporary perception of modernity in style, and the advances gaining ground in mechanized production, standard sizing, and the very first synthetic dyes.

“A lot of what goes on in modernity, if you think about it as a concept but also as a visual, has to do with trust in the machine,” she explained. “Trust in the machine to make life easier as a labor-saving device, but also to give people access to more practical things and to better their lives. That is definitely something that was happening in fashion.”

In the true spirit of the Industrial Age, mass production in the 1800s allowed for the production of new styles more swiftly and cheaply than ever before. The fashion cycle was getting faster, and more people could now afford to follow it. Power looms and sewing machines surely drove advances in textile manufacturing, but inspiration came from the world beyond fashion, too.

While the invention of an inexpensive process for mass-producing steel in the 1850s powered developments in infrastructure and architecture–sturdy steel rails in place of iron paved the way for train travel at greater speeds–the fashion industry also spotted potential for an improvement to current style. At a time when life was speeding up in so many ways, the new technology had the potential to make women lighter on their feet.

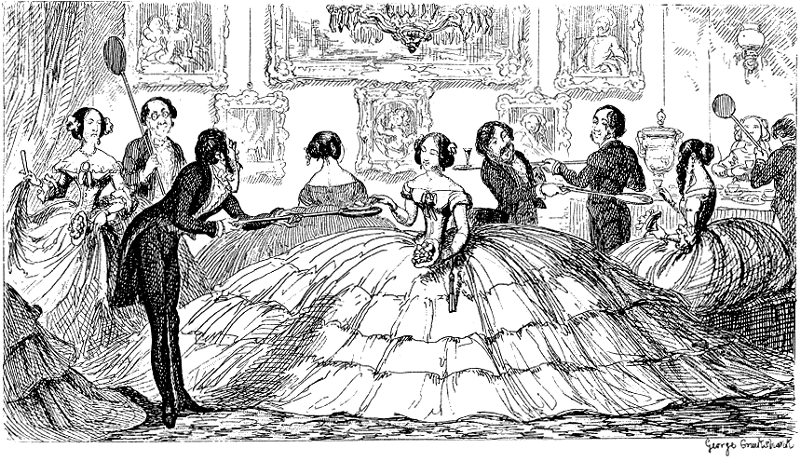

Made of suspended hoops of spring-steel, the crinoline cage was designed to be worn below the skirts of well-heeled women and girls. It successfully achieved the highly desirable bell-shaped skirt of the moment, but with a fuller structure and much less fabric.

“Before the crinoline, to get that big, fabulous bell shape you had to wear tons and tons of shaped petticoats,” Deihl said. “So even though today we might think of it as totally old-fashioned and anachronistic, in reality it was a huge improvement. It was lighter, air could get up underneath, and it was not putting all this pressure on your waist.”

Following the first patent in Paris in 1856, manufacturers across Europe and America got in on the act. Because the crinoline cage could be produced quickly and comparatively cheaply, more women could now sport the desired look–and it wasn’t half as hard to wear.

Cutting-edge as the design may have been, the costume itself remained cumbersome and accident-prone, with fire being a particular hazard for wearers. No more practical in a crowd or in the workplace than a paper dress in the rain, the trend was roundly mocked in contemporary media, and lower-class workers were cautioned not to wear the caged dresses to their factory jobs. Designers had used technology to perfect and enhance an existing style–without noticing that life had moved on. By the mid-1860s, the bulbous-shape style of the crinoline had deflated, with its front becoming significantly flatter.

Some of the crinoline’s loudest critics were members of the “dress reform” (or “rational dress”) movement, who advocated a more comfortable and individualized style of dress, less in thrall to the ever-changing fashions. From early (and largely unsuccessful) efforts by Americans Elizabeth Smith Miller and Amelia Bloomer to popularize the billowy trousers that took the latter’s name, to a later, more effective focus on developing less restrictive undergarments, the movement was active through to the 1890s. For some reformers, opposing the perceived “moral excess” of extravagant fashions like the crinoline was one motivation, but at a time when more women were taking up work and participating in leisure activities, health and the ability to move freely in their clothes were the major goals.

The arrival of the first “safety bicycle” in the 1880s saw many men and women across the Western world take up cycling over the next decades, and there was a growing sense that a corset and full skirt weren’t going to cut it on two wheels. Though women’s clothes were center stage, certain practical innovations in underwear, such as the liberty suit or union suit (rather like a onesie), also carried over to men.

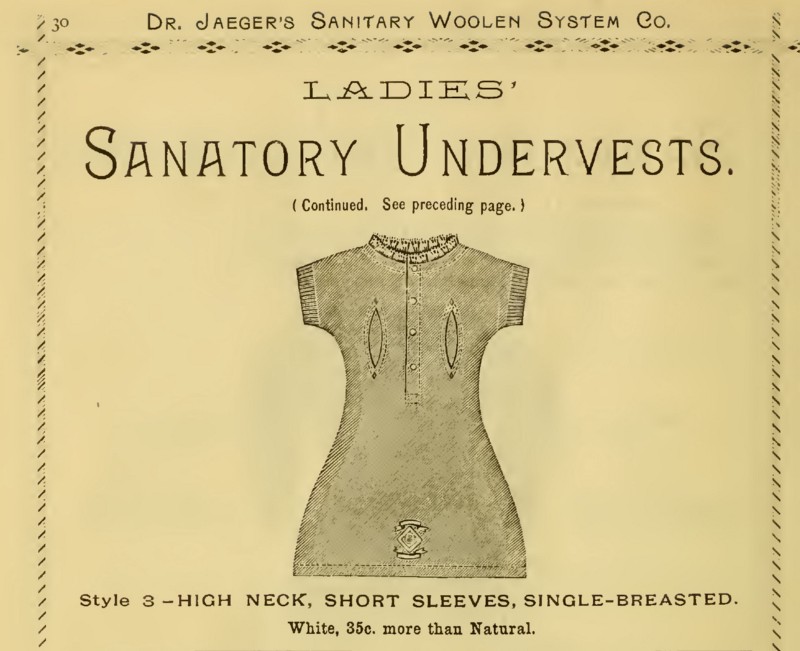

But the wider rational dress movement had its share of the ridiculous, too. In the 1880s, in a strange precursor to the pursuit of smart fabrics and wearables today, German zoologist Dr. Gustave Jaeger brought to the table his own innovations in underwear with the Sanitary Woollen System Company. Arguing that only animal fibers, and wool in particular, should be placed near the skin, Jaeger claimed that the natural scientific properties of the garments worked with the wearer’s skin to actively guard against diseases like dysentery.

During a time of ongoing scientific discovery, advances in medicine, and an increased focus on public health and hygiene, it’s easy to see why Jaeger’s system (with its supposed basis in biology) made sense to a small but growing body of customers.

Serving men, women, and children, the collection included vests, corsets, and stockings; outerwear such as trousers and coats; and even a range of accessories like the “catarrh-fighting” handkerchief. Over the following two decades, the trend spread from its European origins as far afield as Australia and Canada, and celebrity fans included explorer Ernest Shackleton.

Today, the British retailer founded in 1884 in Jaeger’s name continues to occupy a prominent place in fashion, but shoppers will be hard-pressed to find woolly underpants in its store. Jaeger’s system, in its original prescriptive form, did not endure long into the new century.

As Deihl and Cole note in their book, however, the emphasis on health and comfort that early dress reformers favored did have a lasting influence on the development of clothing for sports and leisure.

In the first part of the 20th century, it was the science of synthetics that caused a flurry of excitement in fashion design. A hunt to find a cheaper replacement for silk began in the mid-19th century, and by the 1920s efforts were gaining considerable ground with two of the very first man-made fibers, rayon and cellulose (fabricated cellulose), emerging on the market. As the Great Depression struck much of the Western world, the urgent need for cheaper fabrics saw wide adoption.

“By the 1930s, the processes were–if not perfected–much improved,” Deihl said, “and so many people who couldn’t afford silk could now wear reasonable substitutes. At the high end, you had designers like Elsa Schiaparelli, who is really one of my favorite designers because she was so experimental. She loved cellophane, she loved rayon, and she loved the zipper, which was also a new emerging technology.”

In the decade’s final flourish, nylon was introduced at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. Developed a few years prior by DuPont, the material was instantly game-changing in its ability to replace the pricey and delicate silk in hosiery, a staple of women’s wardrobes.

“It’s hard to really overstate the importance of nylon in fashion,” Deihl said. “To have stockings that fit you, that were strong, and that could match the color of your legs, this was just extraordinary to people.”

Today the global fashion market is valued at $3 trillion, with the largest domestic market in the United States worth $385.7 billion. A huge driver of that value is customers’ love for buying and wearing clothes, but not necessarily keeping them.

American consumers alone generate a collective 15 million tons of textile waste annually (not including leather), of which only 15 percent is reused or recovered, according to the EPA.

Though a steady acceleration in the market can be traced from 19th-century industrialization, it’s the expansion of retailer Zara–with its highly engineered supply chain–that is credited with delivering today’s truly “fast fashion.” Opened in 1975, the Spanish retailer focused on providing what customers wanted faster than anyone else. It streamlined a design, manufacture, and distribution model that, by the late 1990s, allowed a product to materialize from drawing board to store in under 15 days. That’s compared to an industry average of around six months.

When Zara opened its New York store in 1989, it was the retailer’s first outside of Europe and only the second outside of its native Spain. By the end of 2000, it had expanded to more than 400 stores in 25 countries. In doing so, Zara relied heavily on the evolving age of connected information technology, linking each of its stores to its headquarters’ network computer to closely monitor how clothing was selling–along with what, exactly, customers were looking for. Real-time data played a bit part in choosing fabric, cut, and price points for any new garment.

With the traditionally long lead times of fashion magazines and runway trends overtaken by the immediacy of the web and, later, social platforms, Zara’s model has been quite obviously contagious.

With mounting concerns over where all our unwanted clothes end up–and the zeitgeist of today heavily weighted toward the concern of climate change and the environment–it’s no wonder that a current focal point in fashion is sustainability.

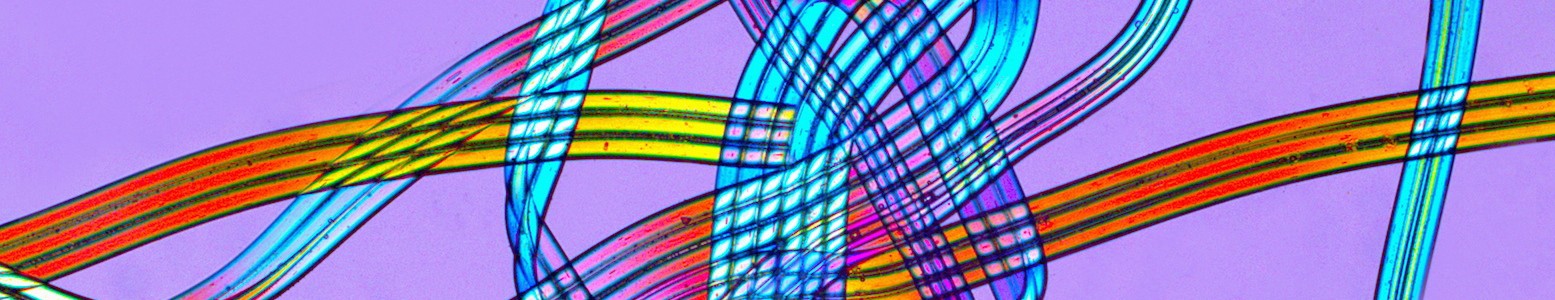

In one new sector, biologists, engineers, and designers are working together to create a new generation of fabrics using “biofabrication,” or by cultivating materials from living cells. Contained within that practice is a field of huge variation, sourcing materials from yeast, bacteria, and other living cells.

Suzanne Lee, a pioneer in biofabrics and founder of the annual Biofabricate event, is something of a figurehead in the sector. As chief creative officer at the Brooklyn-based startup Modern Meadow, she is the voice of a multidisciplinary biotech team focused on creating animal-free leather. Using biofabrication, the company is developing a process to grow collagen into a sheet of material that can then be tanned to create leather.

“Biofabrication enables you to design and engineer the material from the bottom up,” Lee told me. “Until this point in history, we’ve had natural materials and synthetic materials. Now, we’re going to take some of the performance qualities that we rely on from a synthetic fiber, with some of the comfort and aesthetic that you might get from a natural fiber, and bring those two elements together to create these bioengineered, biodesigned, and biofabricated materials of the future.”

While it all sounds very new-agey, it’s Lee’s own research over the last decade that has convinced her a more conservative model of innovation will first be necessary to initiate wider change. After previous work developing Biocoutureâ„¢, an innovative microbial cellulose created through fermentation, she moved away from the project when it became clear that the economics of scaling the process didn’t add up. Competing in the marketplace against a low-cost commodity fiber like cotton simply wasn’t viable. For a biotech approach to succeed at an early stage, Lee realized it must instead target materials with a high market value, as did those early synthetics like acetate and rayon.

“That’s why if you look at the early companies in this field, they’re either doing leather or silk,” she said. “If you can bring new performance functions or new aesthetics to those materials, then potentially you can compete with the current pricing level in the market.”

Alongside Modern Meadow, companies like Bolt Threads are working to replicate and enhance the silk production of spiders and insects, and MycoWorks is developing a leather based on fungal mycelium.

“People want sustainability, but they want it at the same price that they’re used to paying for their petrochemical synthetic,” Lee said. “They don’t want to pay for the additional R&D that it takes to produce these materials, and that will always be the challenge in fashion.”

It’s a dilemma that strikes a chord with Hélène Smits, founder of the circle textile program at Circle Economy in the Netherlands and now director of her own company, Stating the Obvious. Working at the other end of the drive toward fashion sustainability, Smits is part of a growing movement that encourages brands to adopt a holistic view of the entire value cycle of their clothing by “closing the loop.”

Smits thinks current “fashion is a high-paced, cost-driven, but not very innovative industry.” People may confuse all the changing designs with innovation, but “basically that’s the only thing that changes–a lot of the industry has remained the same for many, many years,” she said.

While smaller startups are driving advances in recycling technology, it’s the larger corporations that have shown willingness to divert funds toward sustainability. H&M, which has set a goal for becoming 100 percent circular (although it hasn’t yet announced a time frame for the initiative), recently invested $1.1 million through its charitable H&M Foundation into a global prize to fund innovation in the sector. To put that in perspective, net profit for the retailer for the second quarter of 2016 was $649.6 million.

A circular approach means changing the way textiles are designed, produced, distributed, and recycled so that once produced, in theory, a material need never be disposed of. As textile-to-textile recycling equipment improves, the ideal end goal is fully circular, chemical recycling that can recover fibers to virgin quality.

At present, the low cost of virgin fibers such as cotton make it prohibitive for recycled fibers to succeed at market. However, as second-hand textile markets become saturated and collectors struggle to resell clothing, their economic case strengthens. “These values are decreasing, so the light at the end of the tunnel is the high-value textile-to-textile recycling, which is already possible [mechanically], and is in development for chemical,” Smits said. “When that technology can be commercialized, I really can see that being a tipping point in closing the loop.”

It could be a long wait, though. Some estimates place the technology for market-ready, closed-loop textile recycling at least five to 10 years away, and that’s only for certain fabrics. For natural and synthetic fiber blends like polyester and nylon, there is currently no closed-loop system at all.

Assessing the potential for a new technology or textile in fashion requires an understanding that lasting impact overnight isn’t a thing–and even the best laid plans may turn out different than expected.

Lee, who explored the role of science and technology in her 2005 book Fashioning the Future, emphasizes that for any innovation the most fundamental consideration is time. And lots of it.

As a point of proof, she cites the evolution of Lycra, first developed by DuPont in 1958. “In the 1980s you saw Lycra as a material being used in the exercise industry, and it was very much a niche application,” she said. Today, it’s in everything from men’s suits to women’s jeans. “Lycra allowed designers to work with completely new silhouettes, because you didn’t have to have seams in garments. It’s an incredibly transformative material, but it’s an innovation that is decades-old, and its full impact across the world is really only being realized now.”

Lee therefore understands the biofabricated materials she’s involved in developing as similarly first-generation. We should see their impact revealed throughout the rest of the 21st century.

Or, maybe we won’t. There’s always the possibility that advances in technology will tempt us with something different, or the spirit of this age will shift its style focus anew.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Sartorial section, which looks at the impact of science and technology on how we present ourselves to each other. Click the logo to read more.