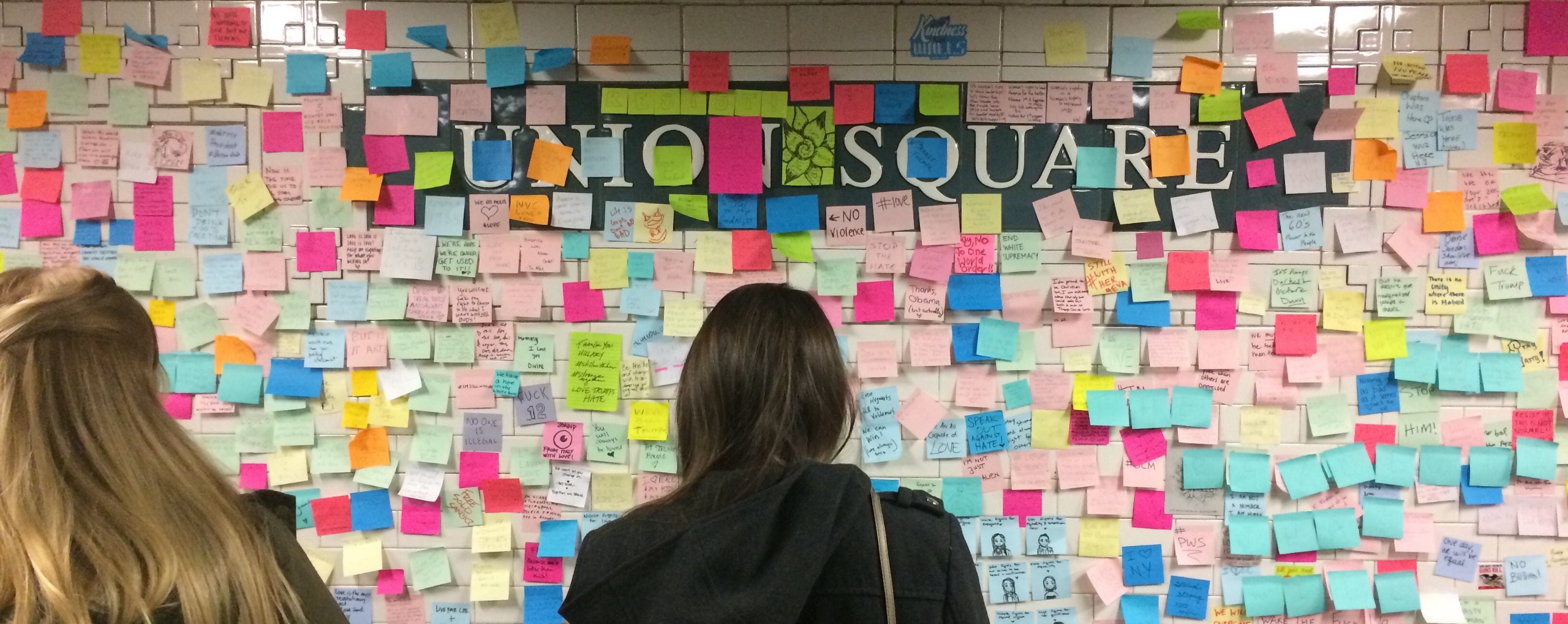

The election of Donald Trump sent me careening between anxiety, fear, and determination, a blender of emotions shared by many of my fellow New Yorkers. For weeks, the Union Square subway station turned into a space for “subway therapy,” where thousands of people built a collage sharing their reactions, worries, and hopes for the future on an underground wall. The transit infrastructure was, for a time, serving as civic infrastructure, connecting those who used it with their fellow passengers.

On a day-to-day basis, public transit can often seem to be a space of disconnect from those traveling next to us. A 2016 study of New Jersey downtowns by the Mineta Transportation Institute found little relationship between living near a train station and measures of civic participation, such as volunteering. In 2014, political scientists from the University of Connecticut found no connection between being politically engaged and living in a neighborhood where few people drive to work. Meanwhile, in a 2014 Harvard experiment, researchers paid Spanish-speaking actors to wait at Boston-area train platforms during rush hour day after day. Surveys of commuters at those stations found that white, English-speaking people demonstrated measurably more negative views of Spanish-speaking immigrants when compared to other parts of the United States, though these attitudes softened over time.

Even so, activists across the world are leveraging the power of public transit as a place of common reference for the people who ride it–as a common space in cities full of difference.

“Eight million people are on the subway and bus every day in New York City. That should be the most powerful constituency in the state of New York,” John Raskin, the executive director of the Riders Alliance, tells me.

It isn’t, which helps explain why, on a winter day in 2016, volunteers and staff in dark green Riders Alliance T-shirts were toting a cardboard cutout of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo around an underground train station, taking selfies with subway riders.

The media-grabbing campaign was part of a bigger project to show Cuomo that city residents were holding him accountable for transit. To a remarkable degree, it worked. After months of this kind of shaming, the governor began to “make a u-turn” on transportation.

The Riders Alliance, which was founded in New York in 2012 and now has a staff of seven, is known for its viral stunts. But the core of its mission is painstaking organization across the city, like meeting with retail workers over coffee to win support for faster buses in Queens. According to Raskin, the Alliance has grown to about a thousand members, which includes citizens who have participated in campaigns over the past year, and dues-paying monthly donors. (Disclosure: I’m one of those monthly donors. I also work for a foundation, TransitCenter, which has financially supported both Riders Alliance and MARTA Army, another interviewee for this piece.)

Riders Alliance is at the vanguard of a growing number of so-called “transit rider unions” and rider-organizing groups that have popped up in parts of the United States, from Silicon Valley to Salt Lake City, Memphis to Seattle. Some of these groups are making serious headway in regions where the politics of transit are harsher than in New York.

Pittsburghers for Public Transit (PPT) organizes riders in “transit deserts,” neighborhoods where residents must walk over a mile to get to the nearest bus, or where bus service runs only in the morning and afternoon. Director Molly Nichols, who joined the group in 2014, has overseen six successful neighborhood campaigns aimed at pressuring the transit authority to restore canceled routes and add new service for residents. While Nichols and her staff help facilitate meetings and weigh in on strategy, committees of residents in the affected neighborhoods make the campaign decisions. In Baldwin (a working-class borough south of Pittsburgh), residents gathered over 1,500 signatures to deliver to the transit agency board. They also organized a successful stunt, inviting politicians, transit staff, and the press to walk the mile and a half that separated them from the nearest bus stop. And after a year of effort, they won their bus service back.

For years, Atlanta’s transit system has lacked the most basic courtesies. Most bus-stop signs include only the Metropolitan Atlanta Regional Transit Authority (MARTA) logo, providing no information about when the bus shows up or where it goes. This began to change in 2015 with the appearance of the direct-action group MARTA Army, founded by a dozen students and faculty at the Georgia Institute of Technology. In its first initiative, roughly 300 volunteer “soldiers” adopted bus stops, hanging up laminated signs with schedule and route information.

To understand why these groups matter, it’s important to understand the civic context. Most U.S. groups working to improve transit are made up of professional advocates who work on behalf of transit riders. They conduct research, analyze policies, talk to the press, and meet with politicians. What they lack is the ability to organize transit riders as a constituency, which these groups accomplish by repeatedly engaging volunteers and asking them to put in considerable effort. Simon Berrebi, a co-founder of the MARTA Army, describes the effect as “creating a network of “‘power users’ who can be mobilized for public transportation.”

They also intentionally organize riders across neighborhoods and age groups, and across racial and class lines. “An organization like ours has to be accountable to the broad range of communities that rely on public transit,” Raskin says, pointing out that this also has political value.

To accomplish this, Riders Alliance organizers canvass in parts of the city that are underrepresented, like the Bronx. They intentionally groom volunteer leaders with diversity in mind. And they choose issues that resonate across different demographics. One of the Alliance’s highest profile campaigns this year is a call for “fair fares”–a discounted fare for low-income riders.

This grows the political power of transit riders, critical in a country as car-dominated as the United States. (Eighty-six percent of trips in the country are made by automobile, compared to 76 percent in Ireland and 46 percent in Switzerland.) As the Congressional staffers who wrote the anti-Trump action manual Indivisible point out, politicians view people like Riders Alliance members, PPT’s campaigning citizens, and the MARTA Army’s “power users” like you might view a pack of wild dogs: hopeful that they can be won over, but with an intense fear of being thought of as prey.

This dynamic helps explain what happened last summer in Atlanta. When I first heard about the Army’s work printing and hanging up bus signs, it immediately raised questions about why volunteers were doing something that seemed like a core government responsibility. Their adopt-a-stop plan worked, though: In June, the state of Georgia agreed to pay $3.8 million for new bus-stop signs throughout the region.

In countries outside the United States, there tends to be a stronger political consensus that transit is necessary for cities to function. Transportation systems can be a vibrant battleground for social movements, led by much larger groups than those at work in U.S.

Over a decade ago, the Movimiento Passe Livre (“free pass movement”) swept through Brazilian cities, calling for free public transit. Transit fares were the spark for the country’s massive 2013 protests, where hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets to express anger over government corruption and funds diverted to projects like Olympic stadia rather than the needs of everyday people. At the time, Brazilian economist Samy Dana found that bus fares in Rio and São Paulo take up a larger part of the average person’s salary than in Santiago, Buenos Aires, Madrid, and London.

The national protests invigorated local movements around the country. In Belo Horizonte, Brazil’s sixth-largest city, the group that has carried the torch is Tarifa Zero (“zero tariff”). Tarifa Zero regularly mobilizes hundreds of protesters who chant songs, fill the streets, and occupy plazas.

Detractors have accused the group of utopianism, as its demands are not restricted to free transit; the group also seeks greater democratic control over contracts with bus operators, to be enshrined in the city’s “organic law” (charter). Members of the group have been elected to city advisory boards and developed sophisticated, persuasive materials and reports on the state of local transit. Activists have even organized a free “busuna sem catatracas” (bus without turnstiles) to draw attention to the cause.

But the heart of the group is street protest and deliberate decision-making. Tarifa Zero makes decisions “horizontally,” through consensus and without appointed leaders. In fact, when I contacted the group through its Facebook page, the page administrator told me that any questions I had would be submitted to the group at large, and should be attributed to the group.

The size of Tarifa Zero seems to depend on how you define “membership.” On the one hand, meetings typically consist of about a dozen activists, although as many as 100 people have attended, according to the group. On the other hand, Tarifa Zero regularly mobilizes rallies with 400″”500 protesters or more. Over 21,000 people follow the group’s Facebook page. And the “bus without turnstiles” is financed through T-shirt sales and crowdfunding. What’s clear is that the group has had considerable impact, rolling back fare increases multiple times and winning substantial media coverage.

Of course, none of this has stopped the transit authorities from proposing new raises. The struggle seems perpetual, and yet there’s value in the struggle itself. Group members told me their newest initiative was helping residents of Aglomerado da Serra, a favela (informal settlement) advocate for bus service. “It’s a different type of interaction than the ones we had before,” Tarifa Zero members said, one that has the group in a support role and some of the city’s poorest residents out front.

Perhaps Tarifa Zero member André Veloso put it best in a blog post reflecting on the group’s first anniversary, where he wrote: “After all this, we transform ourselves and continue to transform ourselves always.”

Israel’s social divisions map directly onto its transportation network. The bus lines that connect Arab neighborhoods are often completely separate from those connecting Jewish areas. A second point of contention centers not around space, but time. Due to observance of the Sabbath, public transit in most Israeli cities stops on Friday and doesn’t resume until late Saturday.

Secular activists have cried foul on two grounds: first, as an intrusion of religion into an essential public service, and second, as backwards urban policy that compels people to purchase private cars, worsening the environment and social inequity.

Increased public transit was one demand of 2011 mass “social justice” protests calling attention to quality-of-life issues in Israel. But it’s a more recent campaign that has given the issue new life. In September 2014, Rosh Hashanah and the Sabbath led to four straight days of transit closures. Naama Risa and Reshef Eisenberg, two Tel Aviv residents, took photos of themselves with signs declaring that urban residents were under curfew. Others followed, turning the effort into a viral protest that grabbed media attention.

Thirteen thousand people now follow a Facebook discussion page created by Eisenberg, which hosts a stream of videos, memes, and stories of people missing out on time with family and shelling out for exorbitant taxi rides. The “24/7 public transportation” activists have protested near metro stations and outside the house of a national lawmaker. Though the group was founded in Tel Aviv (which has the country’s most extensive transit network), members also come from Jerusalem and Haifa, according to Eisenberg.

Late last year, legislators rejected a bill that would have allowed the operation of public transit during the Sabbath. But local politicians are feeling the heat. In June, five local councils announced they would begin operating limited Sabbath transit in the form of shared taxis, minibuses, or free transit, which they say is allowed under existing law. And 24/7 public transportation has become a regular cause for Haaretz, the country’s major left-leaning paper.

Israeli blogger Shalom Boguslavsky has lamented that, in Jerusalem, the ostensibly “professional text” of urban planning is in fact a “political text.” But this is true of every country.

The Tarifa Zero activists are responding to transit politics that squeeze the working and middle classes. Similarly, rider-organizing groups in the United States exist as an attempt to bolster the weak political position of Americans who use transit. What these activists understand is that public transit is a space with a dual characteristic: It is a shared space, creating common experiences among its riders that can be leveraged for organizing politically. Simultaneously, it is a contested space that is the target of organizing from outside interests.

I never visited the “subway therapy” wall at Union Square. But the power of transit to become a space for civic engagement was still made unexpectedly vivid to me last November. Two days after the election ended, I got an email from John Raskin, as did every member of the Riders Alliance. The message, which was also posted as an open letter on the organization’s website, read:

“We are known as a transit organization; in reality, we are a democracy organization. Our mission is not only to win better trains and buses; it is to make our city more just, more inclusive, more compassionate, and more sustainable.”

In the end, a train won’t magically make us more tolerant, or more engaged with our neighbors. And yet public transportation can be a powerful platform for political action, and it can make our cities themselves stronger and more equal.

For it to serve those purposes, riders themselves must be involved in the fight for the transit they need. John’s letter reminded me, and my conversations with a world of activists showed me, that we have to work to get there together.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Together in Public section, on the way new technologies are changing how we interact with each other in physical and digital spaces. Click the logo to read more.