Editor’s note: The following excerpt is from “The Black Speculative Art Manifesto,” to be published in the forthcoming art catalog Unveiling Visions: The Alchemy of the Black Imagination by John Jennings and Reynaldo Anderson.

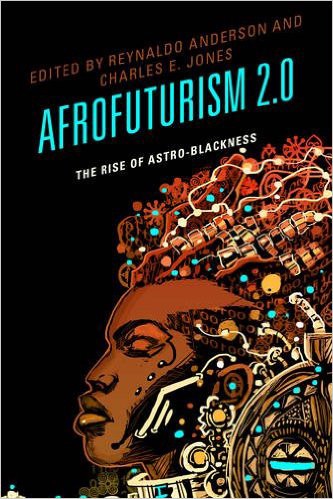

Over the last decade an embryonic movement examining the overlap between race, art, science, and design has been stirring and growing beneath the surface. Afrofuturism 2.0 is the beginning of both a move away and an answer to the Eurocentric Hegelian perspective of the 20th-century early formulation of Afrofuturism that wondered if the history of African peoples, especially in North America, had been “deliberately” erased.

Or, to put it more plainly, future-looking black scholars, artists, and activists are not only reclaiming their right to tell their own stories, but also to critique the European/American white digerati class of their narratives about others, past, present, and future–and challenging their presumed authority to be the sole interpreters of black lives and black futures.

Therefore, propelled by new thoughts and creative energy, members of this black speculative movement have been in creative dialogue with the boundary of space-time, the exterior of the macro-cosmos, and the interior of the micro-cosmos. Yet, there is historical precedent for this movement around the concepts of the color line, the color curtain, and the digital divide.

In 1903 W.E.B. Du Bois published his great work The Souls of Black Folk, drawing on the disciplines of sociology, anthropology, autobiography, and history to make his argument in the era of Jim Crow and imperialism. He noted: “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line, the relation of the darker races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.” Two years later, Albert Einstein proposed his special theory of relativity that confirmed the relationship between space and time, postulating that the laws of physics are invariant in all inertial systems and the speed of light in a vacuum is the same for all observers. Three years later, between 1908 and 1910, Du Bois would draw upon ideas from natural science, humanities, and social science to write the speculative short fiction story “The Princess Steel” with characters like a black sociologist that invented a “Mega-scope” that could see across space and time. The incorporation of the speculative perspective by Dubois would help him creatively amplify his ideas into a”means for perceiving material history”. Later, in the 20th century, Kwame Nkrumah and other leaders would organize the Bandung conference in 1955; a meeting for the Dark World that called for “the de-occidentalization of the earth.” The author Richard Wright, a conference attendee, reported the ideas, promoted, and discussed them at length in his work The Color Curtain. This event would influence the imagination of activists like Claudia Jones, Malcolm X, Steve Biko, and Thomas Sankara.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1qjiQwD7VCI

Although over the course of a generation many of these radical initiatives would be repressed or betrayed, the seeds for a black speculative movement that would challenge white racist normativity and black parochialism would be sown by creative intellectuals, mystics, and artists like Sun Ra, Fela Kuti, George Clinton, Max Beauvoir, Octavia Butler, John Coltrane, Alice Coltrane, Samuel Delaney, Jimi Hendrix, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and others too numerous to name. Finally, at the end of the 20th century, scholars like Molefi Kete Asante, Audre Lorde, Chinua Achebe, NgÅ©gÄ© wa Thiong’o, Greg Tate, bell hooks, Cornel West, and Tricia Rose catalogued the growing deterioration and anomie of black cultural production and dislocation in relation to the transition to a neo-liberal multinational political-economic matrix. Furthermore, Anna Everett, Alondra Nelson, Alex Weheliye, Kali Tal, and others, via an online forum during the early conceptual development of Afrofuturism, critiqued a global digital divide emerging that reflected technical, economic, and social inequality that prevented Africa, its diaspora, and other countries of the global south from attaining optimal growth or enhancement in political, economic, social, or cultural capital. However, during this time, on into the early 21st century several disparate strands or elements of a new creative Africanist matrix were emerging from previous seeds planted that are adopting speculative design and world-building, a renewed political commitment, as well as the social physics of Blackness or (taking the interface of African peoples, mytho-forms, technology, behavioral science, ethics, and social world as influences).

This manifesto assembles and recognizes the ideas developed between 2005 and 2015 that influenced the emergence of what we call the “Black Speculative Art Movement” (or BSAM), and the event “Unveiling Visions: The Alchemy of the Black Imagination” that established its existence. Moreover, this manifesto explores the question: “What is the responsibility of the black artist in the 21st century?”

Within the Afrofuturist 2.0 frame of inquiry, art scholar Tiffany Barber asserts:

“What is compelling about Afrofuturism is that it is historical in its gesture back to previous debates about social responsibility, radical politics, and black artistic production that surged during the Black Arts Movement (or BAM) of the 60s and 70s. But it rearticulates these debates and expands our understandings of blackness’s multi-dimensionality, the good and the bad, the respectable and the undesirable.”

Not only are Afrofuturism 2.0 and the Black Speculative Arts Movement indebted to previous movements like BAM, but also Negritude, the Harlem Renaissance, and other continental and diasporic African speculative movements. Furthermore, it is a continuation of the work and ideas of Du Bois, Wright, Everett, and others to pierce the color line, the color curtain, and understand the digital divide in the face of the challenges of the 21st century. For example, contemporary artists like Kapwani Kiwanga are now revisiting the ideas of Kwame Nkrumah to envision an Afro-Galactic future. Moreover, the goals of the Black Speculative Art Movement manifesto are structured as a pursuit or open sourced path of inquiry to transform the anomie or collapse in ethics and dystopia in the diaspora and African communities that have been displaced by the collapse of space-time.

Between 2005 and 2015 several events occurred, amplified by emerging social media, that would influence the emergence of BSAM, such as the big short (the global market collapse); the big sort (or re-segregation of people by class, ethnicity, or religion); the election of Barack Obama, racist reactions, and the collapse of the liberal post-racial project; the increased use of crowdfunding and other new technology to design creative projects; increasing environmental stress; the new Jim Crow (or the mass incarceration of African Americans in the United States); the new Scramble for Africa (or the contest between the West and the East for political, economic and resource dominance); the resurgence of Pan-Africanism and outreach to the African diaspora (now incorporated as the 6th zone) by the African Union; the state-sanctioned deaths of black people and police brutality; and the current global black social protest response to localized forms of injustice.

Rather than a unified school of thought, BSAM is a loose umbrella term represented for different positions or basis of inquiry: Afrofuturism 2.0–and its several Africanist manifestations (i.e., Black Quantum Futurism, African Futurism, Afrofuturismo, and Afrofuturista)–Astro-Blackness, Afro-Surrealism, Ethno-Gothic, Black Digital Humanities, Black (Afro-Future female or African Centered) Science Fiction, the Black Fantastic, Magical Realism, and the Esoteric. Although these positions may be incompatible in some instances, they overlap around the speculative and the designed, and interact around the nexus of technology and ethics. Individuals or organizations whose work represents pillars of BSAM would include and are not limited to: Paschal B. Randolph, Toni Morrison, Sun Ra, Amiri Baraka, Tananarive Due, Ben Okri, Nnedi Okorafor, the Afrofuturist Affair, Samuel Delany, Max Beauvoir, Afrika Bambaataa, Jarita Holbrook, Ishmael Reed, Wanuri Kahiu, Andrea Hairston, Sylvester James Gates, Octavia Butler, Octavia’s Brood, Nalo Hopkinson, D. Scott Miller, Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, Steven Barnes, David A. Durham, N.K. Jemison, D. Denenge Akpem, Ytasha Womack, Kapwani Kiwanga, John Akomfrah, and Kodwo Eshun.

For example, in the occidental realm the epistemic boundaries of speculative design is limited largely to objects, how they mediate human experience and are primarily interpreted through ideas originating with the Frankfurt School of critical theory (a body of thought usually dismissive, silent, or Eurocentric in regards to black cultural knowledge-production and performance). Furthermore, this occidental approach limits the framework of the speculative to Western philosophy and science. For example, Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby (2013) argue in relation to speculative design only the present, probable, preferable, plausible, and possible should be zones of concern, noting:

“Beyond this lies the zone of fantasy, an area we have little interest in. Fantasy exists in its own world, with few if any links to the world we live in “¦ This is the world of fairy tales, goblins, superheroes, and space opera.”

However, this approach eschews or avoids alternative speculative cultural worldviews and attempts to establish a system where Europe assumes the teacher position and all others as the receiver. For example, there is a host of historical evidence that demonstrates, via the route of alchemy, magic is a gateway into the study of science. In contrast to Dunn and Raby, Lewis Mumford (1934) previously noted:

“Between fantasy and exact knowledge, between drama and technology, there is an intermediate station: that of magic. It was in magic that the general conquest of the external environment was decisively instituted. For the magicians not only believed in marvels but audaciously sought to work them: by their straining after the exceptional, the natural philosophers who followed them were first given a clue to the regular.”

An Africanist example of this phenomenon is the work of Max Beauvoir, a trained biochemist and Vodou priest that synthesized these approaches in medical treatment as a healer and activist. Furthermore, scholars like Nettrice Gaskins are demonstrating the possibilities of re-conceptualizing African Cosmograms as cultural tools to interact with digital technology, augmented space, and augmented reality.

Moreover, there are implications for culturally situated learning, STEAM, critical making, and holistic health. Finally, novelist Nnedi Okorafor demonstrates in her novel Akata Witch the overlap or merger between magic and technology in an African cultural sphere. Therefore, in contrast to the occidental speculative design approach, BSAM freely embraces the Africanist approach to speculative design and embraces earthly and unearthly intuitive aspects of Esoterica, Animism, and Magical Realism as overlapping zones with other knowledge formations when formulating or conceptualizing theory and practice in relation to material reality. Due to the brevity of this manifesto we do not have the space to explore the global multifaceted dimensions of black art, however, we would be remiss if we did not look at an important argument that black artists and designers in the West have been wrestling with for several generations in relation to politics.

The role of black artists in relation to politics has been debated for roughly the last 90 years. Prominent in these debates is W.E.B. Du Bois’s Criteria for Negro Art published in 1926 that specifically focused on the politics of beauty, propaganda, and social recognition, and noted:

“What do we want? What is the thing we are after? As it was phrased last night it had a certain truth. We want to be Americans, full-fledged Americans, with all the rights of other American citizens. But is that all? Do we want simply to be Americans? Once in a while through all of us there flashes some clairvoyance, some clear idea, of what America really is. We who are dark can see America in a way that white Americans cannot. And seeing our country thus, are we satisfied with its present goals and ideals?”

The authors would like to thank Tiffany Barber, Rasheedah Phillips, Andrew Rollins, Damion Scott, Clint Fluker, and Sudarsen Kant for their valuable comments during the development of this document.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our collection of conversations about Afrofuturism, curated and edited byFlorence Okoye of Afrofutures UK. Click the logo to read more.