On October 29, 2014, British charity the Samaritans, which offers emotional support to those at risk of suicide, announced the release of its Twitter-based app, Samaritans Radar. The app is intended to help the support networks of vulnerable Twitter users by flagging signs of emotional distress. Once you’ve signed up for the app, it searches the Twitter feeds of the people you’re following and emails you if it detects phrases such as “need someone to talk to” or “depressed.” As the app’s tagline puts it, “Turn your social net into a safety net.”

The storm of protest that followed the app’s unveiling suggests that, however well-intentioned, the Samaritans got this horribly wrong.

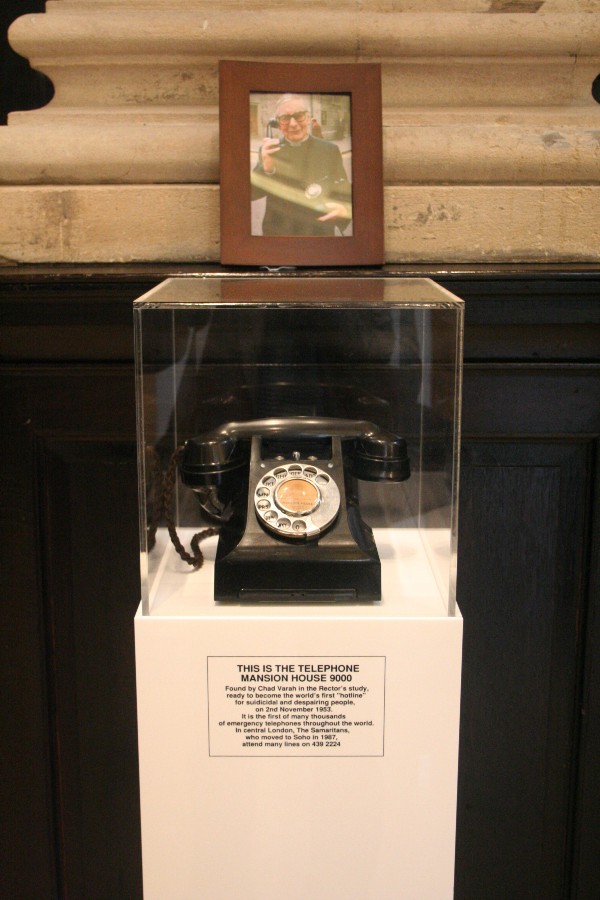

The charity has always used technology to further its mission. It even features in the Science Museum’s new Information Age gallery. The group started the world’s first anonymous 24-hour helpline in 1952, at a time when only about 10 percent of U.K. households had a telephone; it also began an email service in 1994, when only a handful of homes had internet access. Social media seems only natural territory for the Samaritans, as the internet’s a space where anonymity and pseudonymity have been important from the beginning, and where both supportive communities and abuse and bullying are part of the landscape. But in the case of Radar, the charity seems to have allowed technical possibility to override the more important question of usefulness and ethics; in fact, the app’s design is actively detrimental to its intended purpose.

Radar has been critiqued on a number of levels. At the most basic, it is unclear how effective it is at detecting tweets indicating actual distress. As the Samaritans themselves conceded, “It’s not good at sarcasm and jokes yet!” This isn’t necessarily machine-specific–as the Twitter joke trial showed, human prosecutors can have much the same problem–but it suggests that the developers were either ignorant about the prevalence of jokes and sarcasm on Twitter or willing to accept large numbers of false positives with all the potential distress they might cause. It is also unclear whether Radar complies with the U.K.’s Data Protection Act. The app only works on public Twitter feeds, but its tweet-scanning email-sending could be considered automated processing of personal information, which would mean that the various protections of the act should apply. The Samaritans say legal advice suggests that their group should not be considered “the data controller or data processor of the information passing through the app,” but even if it were, an exemption would apply as “vital interests are at stake.” One might argue the legal issues are besides the point, as Radar seems to violate the Samaritans’ own principles of privacy and autonomy upheld in their face-to-face and telephone interactions.

But these are minor concerns compared to the effect the app has had on the people it is supposed to help. As several people have pointed out, Radar seems to be designed for people who might want to help their friends with mental illness, not for the people with mental health issues themselves. Moreover, the possibility that malicious individuals might use Radar to see when a target is in a fragile state seems not to have been considered at all. The design protects the privacy of the Radar user over that of others; Twitter users cannot know if they are being monitored and must opt out or lock their Twitter accounts to be sure they are not. It could be a very efficient tool for the most malignant of trolling. The binary model of privacy that Radar uses also fails to capture the social context of many Twitter posts, where one public user might be in conversation with someone who has a locked account.

Taken together, the data protection concerns, lack of opt-in and potential privacy violations around user consent are issues any app–certainly one representing a charity–should seek to avoid. As a browse of the #SamaritansRadar hashtag shows, the end result of this has been to endanger online safe spaces for many people with mental health issues, some of whom have either locked their accounts or left Twitter.

So far the Samaritans’ response has been to deflect the concerns of Twitter users by setting up an opt-out; the group states that so far over 3,000 people have signed up for the service and it still believes Radar could save lives.

Ironically, it seems like what the Samaritans really need to do here is listen to the needs of potentially vulnerable people–and shut down the app.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Together in Public section, on the way new technologies are changing how we interact with each other in physical and digital spaces. Click the logo to read more.