If you want to understand branding, you can do a lot worse than looking to a bar of soap.

The first bar of Pears soap was produced and sold in 1807 at a factory just off Oxford Street in London. This might seem like a small event, but it reflects a radical change in the way we shop.

Soap was no longer just soap. It was Pears soap, or another type of soap. Manufacturers used external advertising and clever packaging to endow their products with qualities not immediately available to buyers, thereby hoping to bypass shopkeepers and build direct relationships with those purchasing their products. Pears was not alone in this, but the company was an active, early adopter of the technologies of branding, investing heavily in art and competitions, and drawing on symbols of beauty, youth, and empire popular at the time.

The 19th-century context is important. Life was speeding up and people were moving around a lot more than they had previously. Products were also on the move and were more often being produced in mass. Manufacturers had access to much larger markets, and customers had access to a lot more choice. Consumers needed methods for navigating the new and increasingly ephemeral social relationships being formed around their shopping. Brands helped.

Imagine this: Previously, you might have chatted with a shopkeeper about which soap you wanted, or the shopkeeper might have already known your preferences. But now you’re in a new town and in a rush. You need a shortcut, a relationship you can take with you as you travel around. Brands offered a way to navigate these new, untethered times; they were badges of trust repeated across time and space.

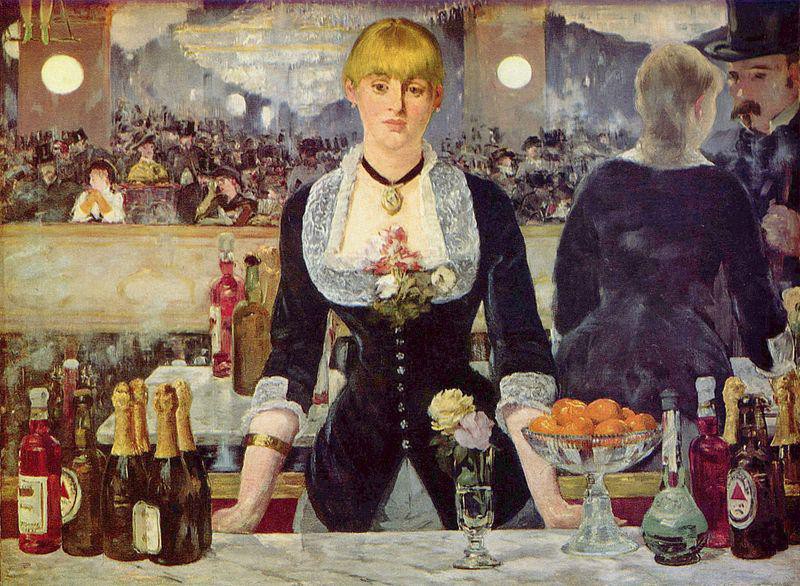

Brands shifted the charisma and knowledge of a flesh-and-blood salesperson to the surfaces of product packaging. This was powerful for soap makers. They could now talk to you directly, endowing their products with all sorts of glamour and relying on advertising to produce symbolic references to lives and ties customers might recognize or aspire to.

Pears wasn’t the first brand, though it was one of the earliest. According to branding legend, an employee of Bass Brewery queued overnight on New Years Day, 1876, to be the first to register the company’s famous red triangle under the U.K.’s Trade Marks Registration Act.

Logos, or at least proto-logos, had been developing throughout the 19th century and before, which is why the U.K. government felt the need to regulate them. It wasn’t long before soup, cola, rice, oats, cereal, and more came branded, with firms rapidly investing in advertising and marketing advice about how to build relationships with customers directly. The launch of any new product meant the need to consider branding.

Branded products also offered a change in how customers moved around shopping spaces. Less reliant on the shopkeeper as a gateway to products, customers navigated themselves (relatively anonymously) through supermarket aisles, enjoying multiple shortcuts as they went.

Brands grew throughout the 20th century, not just in number but in what they came to represent. They no longer marked just a standalone product like soap, but subsumed a whole range of related goods. Shampoo and deodorant, perhaps, and makeup; maybe a magazine, stationery, badges, or a mug. Brands became famous in their own right and sometimes much larger than what they were invented to represent–as seen in the shift from the CND logo to “the peace sign,” for example. Customers even saw the emergence of brandcapes, whole spaces where they were invited to interact with a brand, and brand sponsorship assumed a key role in sports and cultural events. And there was even some pushback, with established companies setting up smaller, apparently more “indie” outlets to appear fresh.

Now, there are meta trade marks–extra logos flagging Fair Trade credentials, Forest Stewardship, or Rainforest Alliance–which sit on top of a host of branded goods. These offer extra information and act as a form of external checks on the symbols the product itself offers. Their existence is arguably also a reflection of our ever-increasing distance from the production of the goods we use. Since some customers seek reassurance about how their products are made, brands hope to distinguish themselves from others by showing off such credentials.

Of course, the web also changed things, offering new opportunities for re-personalizing shopping and shifting power anew. It can be easier for smaller producers to find customers again, in some contexts–via the long-tail effect, if nothing else. And social media means one disgruntled customer can speedily turn into a collective backlash. Pears soap, for example, abandoned a new recipe in 2010 after a Facebook campaign. We’ve seen attempts on the part of brands to get personal in their responses to customers, as well as growing efforts to plug into the power of personal connections to sell products, from brand ambassadors at universities, astroturfing, and names on coffee cups and cola bottles.

Customers also have access to information behind their products. Today, you’re perhaps more likely to stand in a shop Googling–yes, “Goolging,” not just searching the internet–a product than to ask a member of the staff for information. You can check the claims of the branding and are less reliant on its symbols. Still, supply chains are complex and opaque enough that we’re a while away from having access to all pertinent information at the tap of a screen. And even if we could see it all, the technology of branding seems entrenched enough that it’ll still probably remain hard to wade through and distinguish fact from creative creation. And maybe that’s fine; maybe we enjoy some of the sparkle and drama branding endows objects–be they soap or oats, shoes or cola. It’s become part of what we look for in a product.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Histories of”¦ section, which looks at stories of innovation from the past. Click the logo to read more.