The seaside town of Asbury Park, N. J., was badly affected by Hurricane Sandy. A new project, Headlands, puts community involvement at the heart of the region’s preparation for the impacts of climate change, and the community seems keen to be involved. In fact, so many people came to an infrastructure design meeting at the local cinema that the team had to hold two workshops back to back and then stayed behind later to answer questions.

The process “electrified” the community, explained city councilwoman Amy Quinn, who worked closely with Sasaki, the team behind the Headlands project. It mobilized residents already committed to environmental projects in the area, she said, and also brought the concept of climate resilience to a broader audience in the town. As well as using local meetings, the team gauged residents’ priorities, concerns, and preferences with an online tool.

Headlands was one of several proposals put forward as part of a year-long consultation and competition, Rebuild by Design, which targets those areas worst affected by Hurricane Sandy and those that stand to be hit again by future storms. President Obama’s Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force created the Rebuild by Design competition, for which the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has earmarked $920 million in initial funding to build the winning schemes.

From oyster reefs creating living storm breaks off Staten Island, to a new port that will provide a lifeline for emergency services and a new barrage protecting the Lower East Side, the six winning projects–announced in June–range widely in scale and expense.

The competition challenged 10 teams of engineers, designers, artists, and scientists to work with community groups in areas vulnerable to storm surges along the East Coast of the United States and devise a range of potential solutions. Design competitions are common practice in urban planning, but they usually look for solutions to a singular problem.

In Rebuild by Design’s case, however, philanthropic money from a group of funders led by the Rockefeller Foundation allowed space for an extended consultation period with local stakeholders. The project required the teams to arrive at an understanding with government, community groups, and grassroots organizations about which problems needed addressing.

International design teams, which included botanists, hydrologists, Dutch water management experts, and a scuba diver, were charged with creating a layered understanding of community vulnerability. That meant addressing the need to strengthen the social fabric alongside physical infrastructure. The contender projects, presented in October 2013, had to stand up to peer review, both from other teams and the communities they were due to serve.

Henk Ovink, principal of Rebuild by Design, said, “Through this collaborative design process, the teams delivered innovative solutions that bridge the gap between social and physical vulnerabilities. I am so proud of these teams, the communities, and their partners for giving the region a new way forward.”

Ovink is the Dutch government’s liaison to the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force. He is also senior advisor to former Housing and Urban Development secretary Shaun Donovan, who continues to work on the Hurricane Sandy rebuilding project. In addition, New York University’s Institute for Public Knowledge, one of Rebuild by Design’s partner organizations, identified an international team of experts who helped shape the research and engagement process behind the projects.

Other countries have indeed benefited from incorporating community input into climate adaptation measures. In places like Madagascar, the Caribbean, and the Philippines, locals have led and shaped measures to make their communities more resistant to climate change. In the Philippines, for instance, mangroves that provide natural, low cost defenses against storms have become degraded through pollution and deforestation. By combining schemes that improve locals’ main concerns (food security and health) with mangrove management, groups saw the benefits of all three measures multiply. On the island of Samar, mangrove replanting is thought to have played a role in the relatively minor damage the region suffered from Typhoon Haiyan.

Roger-Mark De Souza, director of population, environmental security, and resilience for the Wilson Center in D.C., said earlier conservation efforts were lacking because they were without community support. “Groups worked out that they needed to start with the communities’ concerns–like health and food security–first and then integrate conservation into their work,” he said.

In New York, the designs combine a variety of uses that began with community priorities. Gaining people’s trust early on was important, especially as the design teams needed to balance tensions between local needs and the brief to create innovative projects.

Brie Hensold, an urban planner at Sasaki, said the biggest surprise for the Asbury Park team was finding that, for the community, resiliency meant social unity rather than protection: “We arrived to the city in the wake of Sandy, and imagined that Asbury would be concerned with coastal flooding and sea level rise. Instead, they helped us understand that the most critical path for their future was to come together as a community, overcome the historic divisions that separated the west side from the beach, and unify around future changes. So, our design needed to reach all corners of the city, not just the oceanfront,” Hensold said.

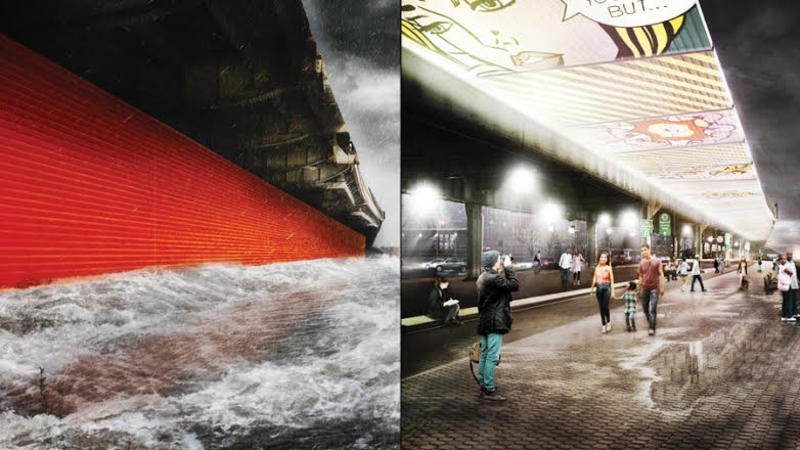

The largest winning project, Big U, is a series of storm breaks that will protect 10 miles of vulnerable low-lying geography. As part of the design, the underside of the raised FDR Drive, which runs along the East River, will gain flip-down panels to ward off floods. The dark passage underneath the road can feel unsafe at night, residents told designers, so the panels will also provide lighting and be decorated by local artists.

Natural infrastructure plays a big part in many of the designs. As projects like mangrove replanting in the Philippines have shown, reinvigorating coastal ecosystems provides natural storm barriers that don’t need to be constantly rebuilt, unlike brittle infrastructure built by humans.

One of the cheapest winning projects is a plan to reintroduce oyster reefs around Staten Island. Oyster reefs create vertical storm breaks that clean up water and grow fast enough to keep up with sea level rise. Alexis Landis, a spokesperson for Scape, the team behind the project, said, “Sea walls and dikes cut communities off from the water. People have embraced this approach, which protects them from future storms and offers benefits such as improved access to the water and ecological benefits.”

Any planning process can be emotional for a community, but Hurricane Sandy’s social toll–coupled with uneven, overlayered response efforts–made some people especially wary of engaging with yet more processes. Strategies such as teams’ efforts to show stakeholders what had been done to incorporate community feedback into the design at each workshop meant people felt their community was truly heard, according to local groups.

In addition, Rebuild by Design’s funders provided money directly to community groups in the process. As relationships developed, many community representatives received funding to play a more active role in creating the local resilience schemes and communicating the risks locals will face in the future as the climate changes.

Now that the winning proposals have been selected, Rebuild by Design is supporting the teams as they refine their designs to qualify for funding. And this model of ultra-accountable resilience planning may not be limited to the East Coast. The $1 billion National Disaster Resilience Competition, announced in September, is a new partnership between the housing department and the Rockefeller Foundation, which looks to replicate the model on a national scale. One of the greatest legacies of the Rebuild by Design model could be the social impact that early, inclusive consultation has on communities.

But with the successes, there has also been disappointment for many communities. Asbury Park’s residents were “devastated” when they found out they had not won funding, said Quinn. As an area that receives aid from the state government reserved for the most financially distressed municipalities, she said the government funding would have been a “game changer.”

Quinn said that despite this setback, the experience has been positive, helping to unite an area divided by geography and relative wealth, and mobilizing people around the need to protect their town. “Before Rebuild by Design, we weren’t in the room talking about [resilience]. Now, there’s a large population in Asbury Park that wants to talk about it,” she said. “This is a very passionate town.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Metropolis section, on the way cities influence new ideas–and how new ideas change city life. Click the logo to read more.