It’s an overcast Saturday morning in Brixton, South London, and a group of renewable energy enthusiasts have collected in the local community center to smash solar cells.

They’re at a DIY solar panel workshop. The event will take all day, but at the end the participants will have made their own solar PV from reused materials, able to charge their phones from the sun. Today, the group is made up of community energy groups from across London, but the team behind the workshops–Demand Energy Equality–work with a range of audiences.

There’s a representative from each of the reasonably established energy groups in Brixton and Hackney, as well as attendees from newer enterprises in Crouch End, Streatham and Vauxhall. It’s a mix of people from a broad range of backgrounds. Although the atmosphere is friendly, it’s hard to imagine them spending Saturday together if it wasn’t for their shared interest in solar power.

Max Wakefield, who is leading the workshop, apologizes for not playing music. The solar panel they made at a workshop the previous week is still recharging before they can power up the stereo. It’s very gray out, but the panel sits on the windowsill, hopeful.

Wakefield asks everyone about their inspiration for coming. Why go to the effort of setting up an urban community energy group, and why come along to a DIY solar workshop? They awkwardly stare at their soldering irons. Someone pipes up with “for the planet,” before another more bluntly interjects with anger. She badly wants to know how we extract and use energy, and thought a community solar co-op was at least a place to start.

“So, who knows what power is?” Wakefield asks. We run through various school-science answers before someone declares, “It’s what’s wrong with the world!” Wakefield chuckles and moves on to an explanation of voltage. Soon we’re all out in the corridor jumping up and down, acting out the role of electrons in a copper wire.

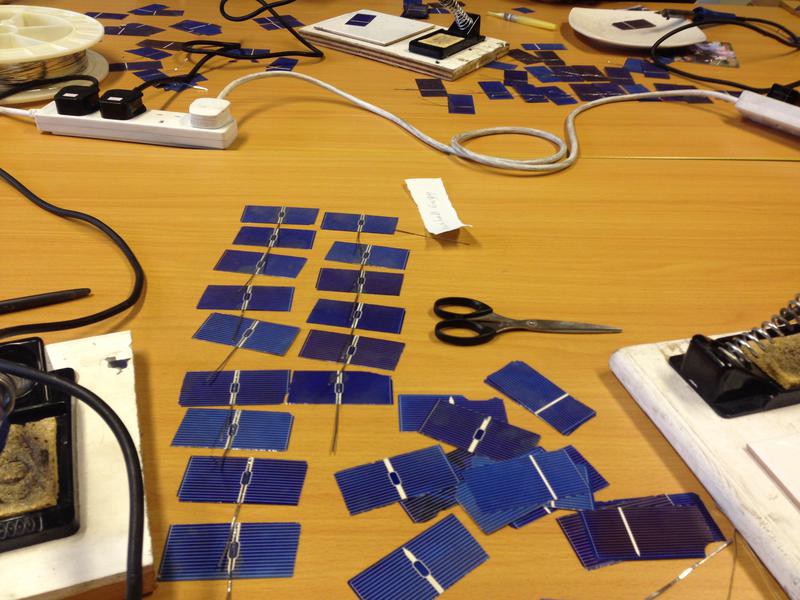

We return to the main workshop room and Wakefield gestures to solar cells, wires and soldering irons laid out on the table. It’s a bit surprising people haven’t been playing with them already. Everyone’s been very well behaved. This is part of the problem Wakefield is trying to address. We’re too reverent when it comes to energy, too passive. We sit back and do what we’re told. And at this point he gets us to reach out and break some old bits of solar cell he’s brought with him.

The cells are brittle and break easily in our hands. As we go from nervously poking at them to a bit more joyous smashing, we notice how wafer-thin they are. This links in to an explanatory point Wakefield wants to address about how we can make enough voltage by weaving the solar cells together. But there’s a social and emotional point too, that the materials we make energy from are fragile, but not so precious and distant from us that we can’t have control over them too.

Wakefield starts to brief everyone on how we’re actually going to go about building the cells. Emboldened, power points are switched on, soldering irons start to heat and the room takes on the smell of a physics classroom as everyone busies themselves with construction. The panel that was sitting on the windowsill has charged, so solar-powered music goes on too.

Later Wakefield explains that the motivations behind these workshops is less about making the solar panels themselves and more about connecting people with energy systems. His colleague Dan Quiggin recently finished a Ph.D. modeling future energy scenarios and this research inspired a lot of their work. “It is an unattractive message,” Wakefield explains, “but we have to use less energy. People don’t want to hear this. It doesn’t sound [like] much fun.”

“So that is why you have to do stuff like this,” Wakefield continues, as he clears up broken bits of solar cell. “We have to de-abstract energy–create a link that’s tangible between people and energy–get them to understand that it’s hard to produce and we take it for granted. How do you talk to people about using less energy if they don’t have much of a relationship with energy? We’re so abstracted from things, abstracted from where our food comes from, where our energy comes from, where pretty much anything we rely upon to live comes from.”

For all the self-sufficiency aesthetic of the workshop, in many ways Wakefield is trying to communicate a greater appreciation of the large energy infrastructures we rely upon. “The money and the expertise and the sheer technical ability that goes into keeping that thing [our energy infrastructure] running is absolutely incredible,” he says. “But we interact with it in a very flippant way. We just press switches.” Though these switches are convenient, Wakefield believes they still represent enough of a relationship for basing the sort of large social change required to deal with climate change.

“So people come to workshops like this and they have discussions that tap right into debates that are happening at the forefront of the debate, rather than a few years behind,” he says. Solar panels are just a means to that end; a way into a larger conversation. It’s something you can build in a day, and finish in a day; a bit easier than building a wind turbine. “We actually spend quite a lot of time talking about how crap solar panels are, at least in the UK,” he laughs, gesturing to the gray sky outside.

As the workshop participants industrially get on with connecting the 36 cells and copper wire required to make the first stage of the panel. It’s a good example of what academic David Gauntlett calls Making as Connecting–people create together and they talk about a range of other things around what it is they’re making. The result is a mix of science lecture, community meeting, public debate on the politics of technology and craft workshop. It’s a mix that seems to work.

They argue, share ideas, plan, learn. It’s also clearly enjoyable. When the first set of cells connected in series are completed everyone’s proud. “I didn’t think this would be fun!” one exclaims. “Yeah, it’s quite therapeutic. How about taking it to an OAP’s home? Green retirement? Beats bingo.” Some people race ahead and distribute extras to those who are moving at a slower rate. One particularly fast participant attributes her speed to how much time she spends with a sewing machine, “upcycling” clothes.

“We’re not the only people who DIY solar panels,” Wakefield explains. “Go on YouTube. That’s basically how we learned to do it. Ultimately it’s not very hard. You just have to have a bit of right disposition to give it a go, and a basic understanding of electricity and you are kind of on your way. It’s not hard to get hold of the stuff.” Still, easy or not, Demand Energy Equality seems to be unusal in using it as a hook for community building and public engagement with energy infastructure (get in touch if you know better!).

In the future they’d like to do more workshops, especially with community groups, and find new ways to fund such work. They’ve worked with the Lightyear Foundation to train people to run workshops in Ghana and there is scope to develop the idea to a wide range of contexts. They’d also like to spend some time exploring other ways to connect people to ideas of energy infrastructure. “[DIY solar panels] is only one way to get people to think about energy. It’s not the only way, so [we’d like to] find a bit of time to sit down and think. What are other things we could do?” says Wakefield.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Power Up section, which looks at the future of electricity and energy. Click the logo to read more.