Steph Curry emerges from the flotation tank, deeply relaxed after an hour spent suspended in salty water. The light shining up from the tank is a liquid blue; shimmering in the dark room, it vaguely resembles the glow of the Northern Lights.

“It’s an opportunity to relax,” the Golden State Warriors MVP point guard explained in a segment on ESPN’s Hang Time. “It’s an opportunity to get away from all the stresses and pull the cord on life. It obviously has some physical benefits as well, with the salt.” Curry’s teammate Harrison Barnes added, “It’s a little bit of a different experience. I haven’t really done anything like this before, but it’s nice to come here and relax. It’s pretty cool.”

These two Warriors were regular visitors to the Reboot Float Spa in San Francisco during the team’s record-breaking 73″”9 season. And they’re right, there are physical benefits to flotation tanks. There’s an autonomic nervous system response–that’s the body’s system that regulates automatic organ function–that causes the body to relax, which in turn is linked with faster recovery times for athletes; it’s also meant to be a source of magnesium, as the skin absorbs Epsom salts from the water.

The biggest benefits we know of, however, are psychological. Starting in the 1930s, sports psychologists have studied the effects of “mental practice” on athletic performance–that is, imagining yourself doing physical tasks, and seeing if it improves real-world performance of those tasks. One 1990 study found that this technique, used when inside a flotation tank, improved athletic performance when compared to athletes who began performing from a state of normal rest.

In the absence of sensory input and distraction, the experience of being in a flotation tank is like opening a blank page in your mind, free from the clutter of day-to-day life. For a basketball player, one hour in a tank is one hour away from the stressful, endlessly repeated highlights of a missed three-pointer.

But for the man who invented the flotation tank, it was supposed to be something else altogether: a way to open a hole to the center of the universe.

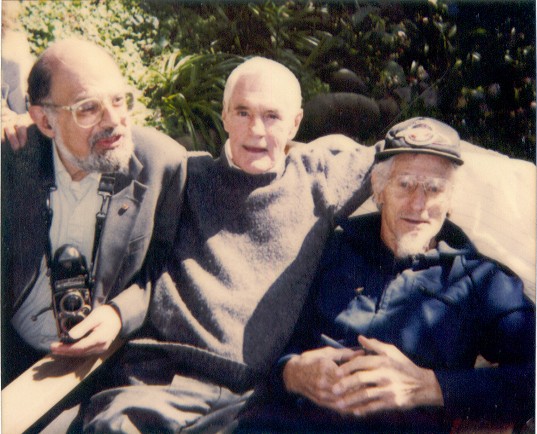

John C. Lilly was the neuroscientist, psychoanalyst, and researcher who invented the flotation tank in 1954. He was, to put it bluntly, eccentric; a man whose quest for esoteric knowledge repeatedly placed him as an outsider within the larger scientific community. (He was also a contemporary and friend of psychedelic-era luminaries like Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg.)

In the 1950s, there were two prevailing schools of thought in neuroscience. The first claimed that the brain needed environmental stimulation to remain conscious–literally, this meant some scientists believed a human brain that wasn’t receiving any external inputs would switch off until they came back. The second assessment said there are brain rhythms that continue without stimuli. Lilly, then a researcher at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), wanted to devise a way to test these assumptions, and that’s when he came up with the flotation (or isolation) tank.

He knew that if he could create an environment that was void of sound, light, and other sensations, he would be able to answer this question about conscious brain activity. Suspending someone in body-temperature water, completely divorced from the outside world, should have worked–but the first flotation tanks had people completely underwater, connected to a breathing tube and wearing tight masks covering their eyes. This was, unsurprisingly, distracting.

The solution was to remove everything and have people float, naked (or near enough), on the surface of the water instead. To achieve this, Lilly dumped as much Epsom salt into the water as possible to increase its density. A typical flotation tank today is about as salty as the Dead Sea, 1.25 times as dense as distilled water.

His experiment worked–he discovered that conscious experience does continue, despite an absence of almost all external stimuli. As he wrote in his autobiography, published in 1978:

“Somewhere, deep within the brain, was a mechanism capable of generating internal experiences completely independent of the outside world, and this settled the issue of what happens in profound physical isolation. The mind does not pass into unconsciousness, the brain does not shut down. Instead, it constructs experience out of stored impressions and memories.”

Yet Lilly’s research took an unexpected turn, as he became more and more intrigued by the nature of those “conscious experiences” he was having in his tanks:

“I made so many discoveries that I didn’t dare tell the psychiatric group about it at all because they would’ve said I was psychotic. I found the isolation tank was a hole in the universe. I gradually began to see through to another reality. It scared me. I didn’t know about alternate realities at that time, but I was experiencing them right and left without any LSD.”

In 1958, Lilly entered the tank for the last time at the NIMH, in his fifth year of research with the institute. His plan for that session was to review the research he had completed in that time; yet what he experienced was like nothing else before.

After following his normal procedure of relaxing his muscles and mind in the tank, he suddenly found himself in what he describes as “a new domain.” He was approached by two disembodied beings, who were, he claims, monitoring and directing human evolution from another dimension, a “subconscious plane.” They told him to start researching dolphins.

Lilly and his wife had always been interested in the intelligence of large aquatic mammals and had previously taken advantage of vacation trips away from the NIMH to study them. Now, with a grant from NASA, Lilly bought a property on St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, which he turned into a research center devoted to exploring communication between dolphins and humans.

It was the early 1960s, and LSD was still legal and being studied in a (somewhat) scientific manner. Lilly had used LSD while in his flotation tank (with mixed results), but on St. Thomas he also began injecting it into captive dolphins in an attempt to foster communication between the two species. The research team waterproofed and flooded an upper floor of the building so that a dolphin could live alongside a human researcher, Margarett Lovatt, in hopes of teaching it human language from a young age, just like a human child.

After months of effort, the research team had managed to get the dolphin–named Peter–to imitate some of the cadences of human speech with its blowhole. That doesn’t mean that the project was a success, however.

Lilly eventually drove away many of his researchers, who found it unconscionable to drug dolphins so casually. By the time his funding was cut, in 1966, his interest in the project was supplanted by his interest in LSD, and the other–more mystical–possibilities that his isolation tanks offered. (Sadly, Peter died shortly afterwards at a facility in Miami.)

In spite of the ethical objections to Lilly’s work on St. Thomas–and his later research in the 1970s, during which he attempted to communicate with dolphins via music and telepathy–his legacy around animal welfare is more complex. His research into marine mammalian intelligence raised public awareness about just how smart whales and dolphins are, and partly influenced the U.S. Congress to pass the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972.

All the while, Lilly was making adjustments to the flotation tank, iterating on and improving its design, while indulging more and more in both LSD and the drug that would become his favorite–ketamine, an anesthetic which can induce a psychedelic state in low doses. He continued to commune with the beings from his first vision in 1958, coming to call them the “Earth Coincidence Control Office,” or ECCO. To this end, there’s a persistent internet rumor that the dreamy Sega Genesis game Ecco the Dolphin was in part inspired by Lilly and his research.

Nonetheless, the tank we have today–whether it’s called a flotation, isolation, or sensory deprivation tank–is the one Lilly developed, intended first and foremost to be a tool for exploring human consciousness.

In his book, The Deep Self: Consciousness Exploration in the Isolation Tank, he laid out his most well-known axiom:

“In the province of the mind, what one believes to be true, either is true or becomes true within certain limits. These limits are to be found experientially and experimentally. When the limits are determined, it is found that they are further beliefs to be transcended. In the province of the mind, there are no limits.”

So, how did we evolve a mind-expanding invention of the hippie era into a mainstream tool for physical therapy and training, found in health centers around the world?

In 1972, Glenn Perry was both a computer programmer at Xerox and acquaintance of Lilly’s. He suffered from debilitating shyness, unable to talk to more than one person at the same time–but after reading Lilly’s autobiography (the wonderfully titled The Center of the Cyclone: An Autobiography of Inner Space) and experiencing the tank for himself, he discovered that his shyness had disappeared.

Deeply affected by the tank, Perry decided to build one for his own personal use. With Lilly’s help, Perry designed what would later become the model for the first commercial flotation tank venture, Samadhi Tank Co. Just like other fads of the era which combined physical health with spirituality–yoga is another notable example–flotation tanks soon began to spread across the United States, and then the world.

Mystical experiences like Lilly’s were, and are, rare, but almost everyone who spends time in a sensory deprivation tank finds the sense of relaxation they induce revelatory. And with widespread use came scientific investigation to better understand their physical and mental effects.

One of the most notable companies to establish itself in recent years is Los Angeles’s Float Lab, which opened in 1999. Its founder, who goes simply by the moniker “Crash,” has appeared on both Tanks for the Memories, a VICE documentary about flotation, and the Joe Rogan Experience, a podcast that regularly tops the iTunes charts.

Crash credits much of the recent upsurge in the popularity of flotation outside of niche communities to Rogan. “Joe’s had an influence on the industry in general,” he explained. “I believe Joe to be the single most important driving feature in the entire industry.”

The first time I visited the float studio that popped up near my home on the Jersey Shore, I mentioned to the owner there I had come to floating through Joe Rogan. He said that by his estimation, about nine out of every 10 floaters seemed to visit thanks to Joe’s podcast.

And, when you hear Rogan describe the float experience, it becomes obvious why so many people are intrigued:

“It’s like a seminar on my life. It shows me all the different issues in my life that I don’t like, that I need to fix, and things that are bothering me. And things about my own behavior where I could have been better, where I’m disappointed in myself. Then, it shows me some things where I’m on the right track. This is good, continue like this, continue thinking like this, continue exploring these ideas. But then, once it gets me done, and clears out all the bullshit from my life, it’s time to look at the big picture.”

According to Reboot Float Spa’s director of business development, Leah Domenici, Steph Curry is the most frequent user of its tank, trying to get a float in once every two weeks.

This brings up the question: Is it a coincidence that the player who smashed his own NBA record for three-pointers made in a single season is also the player most willing to experiment with novel approaches to help him gain an edge over his opponents?

At the highest level of sports, each athlete is physically gifted. Every player on an NBA court at any given time is strong, fast, agile, and coordinated. In the end, which factor separates the good athletes from the truly great? The answer: a mental edge. Namely, focus, motivation, and the ability to manage emotions effectively are what make a player like Curry stand out.

It may come as no surprise that Curry’s head coach, Steve Kerr, is known for evangelizing the importance of mental skills. Kerr cites The Inner Game of Tennis by Timothy Gallwey, a cult classic among successful head coaches, as a major influence. The premise of the book is simple, as Kerr put it in an interview with Sports Illustrated: “How do you get out of your own way? How do you stop the chatter in your mind?”

Curry’s pioneering use of flotation therapy among athletes may be a key factor in helping him do just that.

Ultimately, though, I’d argue that the flotation tank has become popular–with all of us–because we need it. In a modern world where the temptation to continuously bombard ourselves with entertainment, information, and distraction is ever-present, the float tank is a respite.

For that purpose, and a potential host of others that we have yet to dream up, the float tank works. As the Buddhist philosopher Alan Watts said, it’s an “antidote for an age of anxiety.”

Other athletes–and the rest of us, too–wanting the mental clarity of a champion like Steph Curry may want to follow his lead and try taking a float.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Playing the Field section, which examines how innovations in sports affect the wider world. Click the logo to read more.