It should come as no surprise that the music you listen to as a teenager echoes through your neurological pathways more than any other. Teenage music just means so much–it helps you figure out who you are and who you want to become. You listen to the same things over and over while feeling serious feelings. You dance the beat into you, stamp the lyrics onto your memory by scrawling them on school desks and pencil cases. The music you listen to in your youth–even the really awful stuff you pretend you were never into–forms the blueprint for who you’ll be and what you’ll listen to your whole life.

That’s not just me being starry-eyed about my days as a Hanson superfan. It’s scientific fact. Research has also shown that music-induced nostalgia can increase our optimism about the future. The study in question, carried out in November 2013, suggests that nostalgia isn’t just a backwards-looking emotion–and this idea of future nostalgia is reflected time and again in the way we make, record, and listen to music. Popular tunes have always been circular. Even the freshest riffs generally owe a pleasurable chord progression, cadence, or rhythmic break to something written tens or even hundreds of years ago. Everything has in some way been recycled, reworked, reanimated.

Pop music, in particular, relies on tapping into musical tropes you’ve heard before to “trick” you into liking something you’re hearing for the first time. It comes in trends and waves; in 2015, some of the best pop music mined the 80s vault, twinning it with modern production values (Taylor Swift, Carly Rae Jepsen). Last year, Daft Punk made disco and funk seem glittering and new. Currently, R&B production style from the 90s is totally hot. Even the perennially uncool new-age pan flutes and steel pans are fashionable (cheers, Bieber), which I personally attribute to a generation that grew up with The Lion King soundtrack and Dario G on repeat. Everything old is new again, and everything new is old.

Like a Rubik’s Cube of sound, musicians are continually looking back, turning one side and making it into something new. The music of the future will see influence from what teenagers are listening to now for the same reasons that 90s R&B and Britpop are having a bit of a moment: Today’s teenagers will grow up to be radio DJs, playlist curators, journalists, label reps, producers, and musicians, and the same nostalgia for their teen years that drives this generation will drive theirs. It’s not outlandish to suggest that in another 30 years we’ll have a new take on 80s synth pop. The people complaining that guitar music has died probably don’t have long to wait before it crashes back into vogue. Even Jamiroquai may yet have its day again (although let’s hope not, right?).

It’s not just melodies and chord progressions that influence the music that gets made. Digital recording and lower-quality sound files mean that anyone can record music from his or her bedroom or garden shed, leading to a bigger proliferation of “lo-fi”-sounding bands. It’s generally agreed upon that digital music files are of terrible quality. “Like taking Berocca instead of eating an orange” is how musicologist Paul Hanford described them.

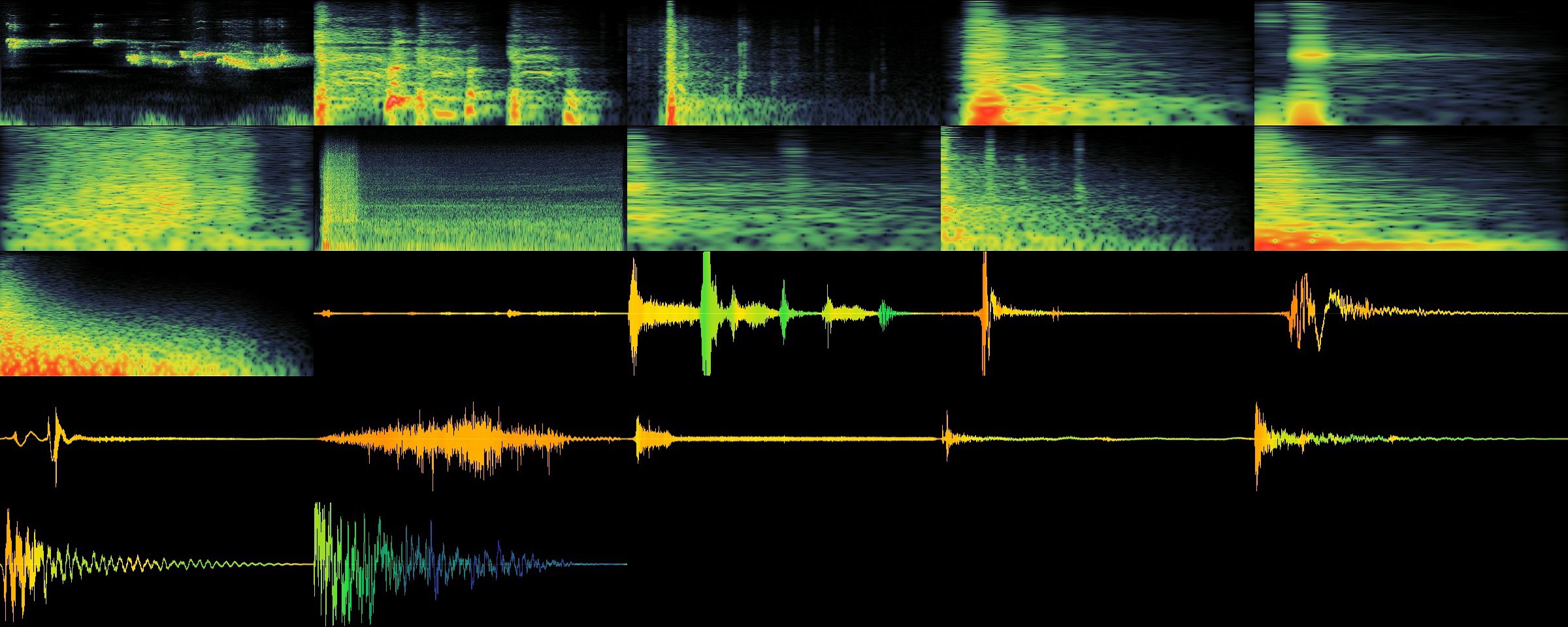

“I record at a much higher quality than most people get to hear,” music producer Paul Curtis explained. “To burn a CD, I have to “‘bounce’ the finished files down to a lower quality, and if an MP3 (iTunes, Spotify, etc.) is required I have to go to an even lower quality still. Vinyl is the only popular format that will capture the full quality of the recordings, as it replicates the whole waveform, rather than digital which only takes step snapshots of it.”

But who can afford to record in a studio? And who, really, can afford to press vinyl, given that the overwhelming demand for the format has resulted in an overload on the handful of pressing plants left in operation? Big name, big money labels pay their way to the front of the queue, leaving independent artists and the dance enthusiasts who kept the format alive out in the cold.

It’s not necessarily bad audio quality that has spurred the return of vinyl as a popular format. “Anyone who says they saw this coming is a liar,” Drew Hill, managing director of Proper, the U.K.’s largest independent distributor of physical music, told Vulture earlier this year. For some, it’s about the fetishization of an old, inconvenient format perceived as somehow superior but mainly just different; for others, it’s about the audio value. Audiophiles sniff at record buyers who gush about the “warmth” of a record, but the pops and noise of spinning vinyl are part of the nostalgia record-lovers seek.

“Analogue will always sound better on analogue,” Hanford explained. “But to a certain extent, it’s cultural rather than scientific. We get used to a certain sound and it becomes normalized. So after 10 years of MP3s, a lot of ears just aren’t accustomed to full-frequency, high-definition sound.”

In the future, will we yearn for the imperfect sound of the overly compressed digital files we ripped from YouTube or streamed on Spotify? Curtis, who as a producer values music quality over quantity, isn’t convinced we’ll see another vinyl-style comeback: “I think that we will always have digital music, I just think the quality will improve–people will look back and wonder how they endured lo-fi MP3s when it all started.”

Nonetheless, Hanford thinks we’ll see an influence from the low-grade MP3 in the future. In fact, there is already a collective marrying between these two distinct forms of nostalgia. Unlikely as it may seem, the PC Music collective has already begun fetishizing the Windows 2000 era, mining the recent past to create the sounds of the future. The young, London-based label is partly influenced by nostalgia for 90s and 2000s Eurodance and its various subgenres–happy hardcore, bubblegum house–but by mixing and matching these bygone musical styles and audio references it’s created something that’s very 2015. It’s a defiantly teenaged style, the kind of electronic music that sounds like a bloody racket to anyone over the age of 25. Tinned beats; glitchy, midi-inspired motifs; and often pitched-up vocals provided by fictional entities whip together into a twisted take on pop music. Chaos reigns. It’s post-ironic, post-internet, post-just-about-everything music, and a watered-down, radio-friendly rehash is no doubt the shape of pop to come.

There is another format worth considering, somewhere between the high-cost audiophilia of vinyl and the low-cost, deliberately imperfect SoundCloud musician: the cassette tape. A spate of tape-only labels have sprung up in the last few years, with Cassette Store Day hoping to do for the chunky plastic boxes what Record Store Day did for vinyl.

If even the cassette, which offers a hissier, noisier playback and the constant fear of battery rundown, can make it in 2015, literally anything could happen. We’ll one day yearn for Spotify ads, or the “ding!” of iTunes completing an import; just as there’ll be musicians, probably those kids and teenagers dancing beats into their souls and scrawling Taylor Swift lyrics on their backpacks as you read this, who will reference, sample, remix, and remake all the sounds we currently hold dear.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Fast Forward section, which examines the relationship between music and innovation. Click the logo to read more.