Crossness Pumping Station celebrates its 150th birthday this weekend. Nestled by a nature reserve far into the east of London, even locals might not know it exists, let alone why it’s important. But it’s an icon in the history of engineering and public health.

To understand the importance of Crossness, you have to go back a little more than 150 years to 1858, a period in London’s history known as “The Great Stink.”

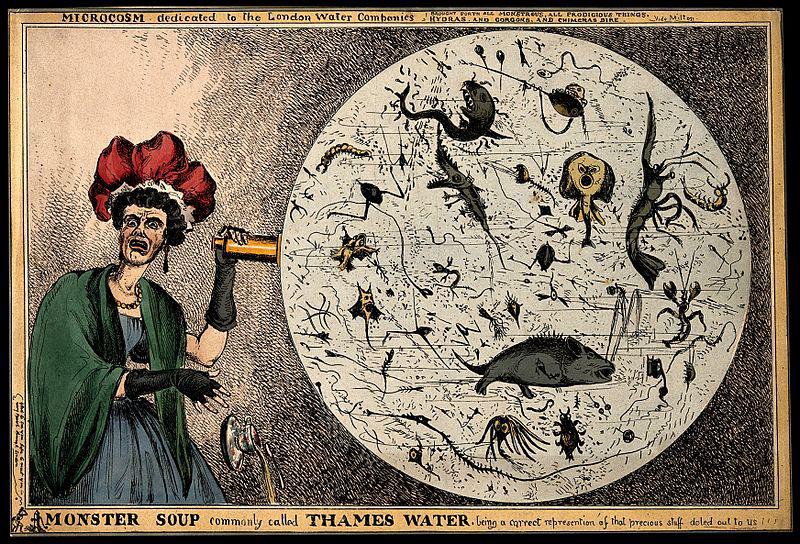

To put it simply, the Thames had filled with sewage and the city smelled horrid. In the 1850s, over 400,000 tonnes of sewage were flushed into the Thames each day–150 million tonnes a year. Once full of wildlife and supporting a large fishing industry, the river was declared biologically dead. The rich could afford to run off to the countryside for better air; the poor had to stay and suffer. This wasn’t just a whiff to make you hold your nose, either. It was a significant public health problem.

As London’s global power had grown, so too had the population of the city. By the middle of the century it had reached about three million. The network of cesspits, built to deal with the waste, wasn’t sufficient. Londoners illegally connected their cesspits to surface water drains, meant only for rainwater. These drains flowed into the Thames, the city’s main source of drinking water. Some of the cesspits leaked methane, causing fires. Polluted water carried cholera and typhoid, and flies feeding on the human waste carried a form of diarrhoea.

Industrial waste didn’t help either. As one medical officer’s report of the time noted: “The cause of the putrescency, and of the blackish-green colour of the water, is admitted by all to be the hot weather acting upon the ninety millions of gallons of sewage which discharge themselves daily into the Thames. Now, by sewage, must be understood, not merely house and land drainage, but also drainage from bone-boilers, soap-boilers, chemical works, breweries, and above all from gas factories, the last, the most filthy of all, and the most likely to cause corruption of the water.”

As Dickens put it in Little Dorrit: “Miles of close wells and pits of houses, where the inhabitants gasped for air, stretched far away towards every point of the compass. Through the heart of the town a deadly sewer ebbed and flowed, in the place of a fine fresh river.”

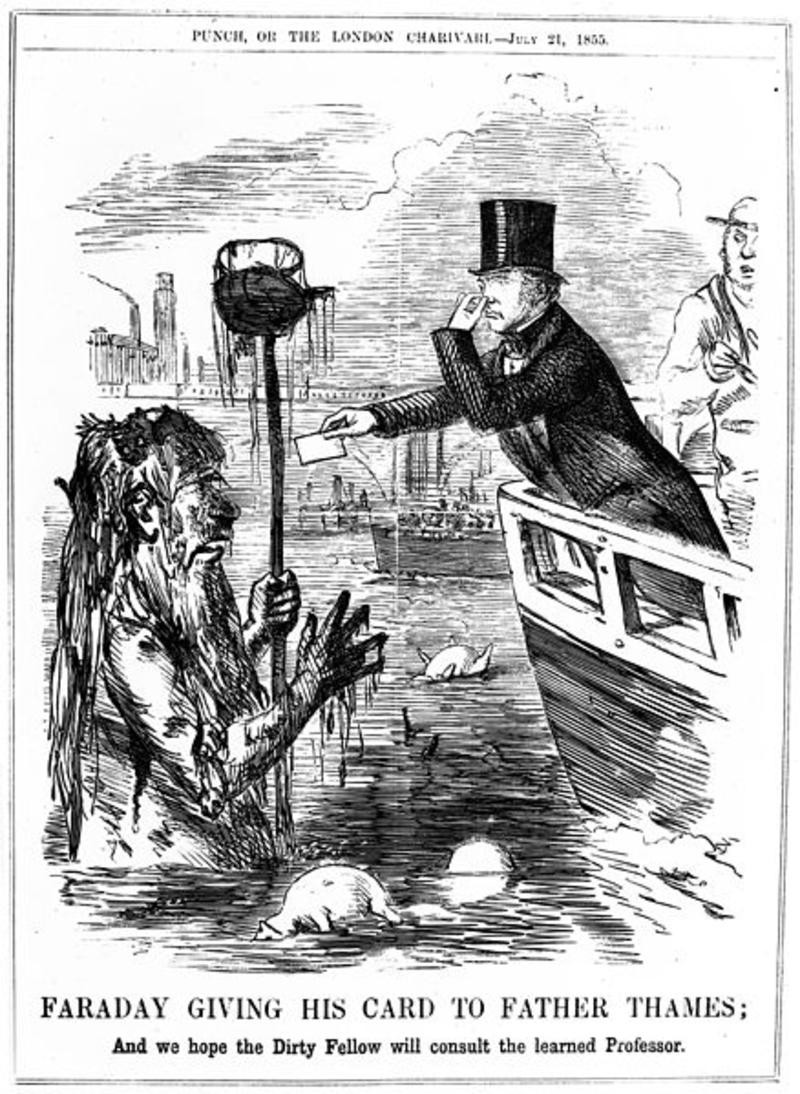

Scientist Michael Faraday–better known for his work on electromagnetism–conducted a series of experiments on the water quality. He tore up pieces of white paper and dropped them into the water to gauge the river’s “degree of opacity.” He concluded there was nothing more than an “opaque pale brown fluid” and a “fermenting sewer” running through the heart of London. He published a letter to Parliament in 1855 but was largely ignored. Then a heatwave hit. Centuries of sewage started to cook.

It was the visionary idea of one Joseph Bazalgette that saved the day and paved the way for London’s modern sewerage system.

His ideas were initially rejected as too expensive, but as legend goes, when in that hot summer of 1858 members of Parliament had to treat their curtains with chloride of lime to hide the smell, they finally decided something had to be done; laws were rushed through to provide £3 million to tackle the problem.

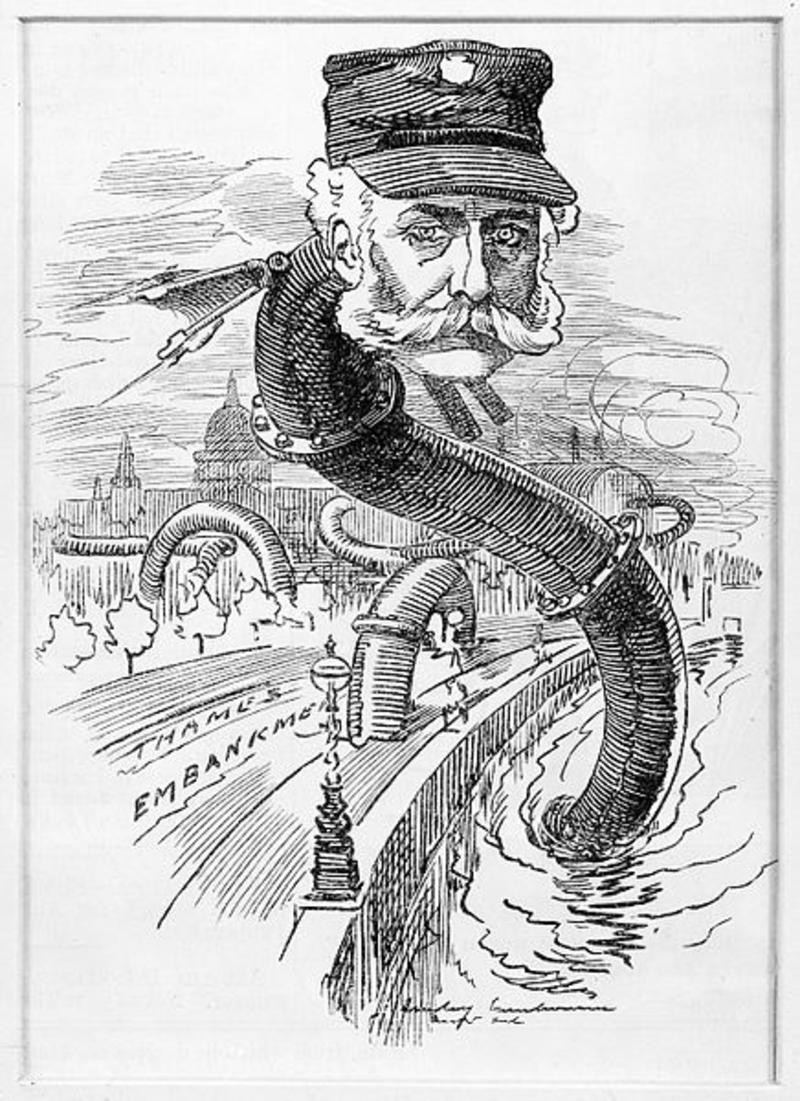

As well as improving flow of the river by building an Embankment to the Thames, Bazalgette proposed an ambitious network of intercepting brick sewers underneath the town. Between 1856 and 1859, 82 miles of brick-intercepting sewers were built below London’s streets. In turn, 450 additional miles of sewers, themselves taking the contents from 13,000 miles of smaller local networks, fed into the main city network. Constructing this complex web involved 318 million bricks and the excavation of 3.5 million cubic yards of earth. Apparently the price of bricks in London went up 50 percent while the new system was being built. It was also one of the wettest summers and coldest winters recorded that century. You have to feel for the construction workers.

The half a million gallons of waste that flowed through this network daily, using a mix of gravity and coal-powered pumping, was moved eastwards. It’d be stored there until high tide and then released far away from the populated center of the town. Two major pumping stations helped it along its way–one at Abbey Mills in North London and another at Crossness on the south bank.

The Abbey Mills station is a beautiful Byzantine-style building, known colloquially as a Cathedral to Sewage. A bit of it was used as the setting of Arkham Asylum in the 2005 film Batman Begins.

Crossness is similarly grand, with spectacular ornamental cast ironwork and an exterior based on a Romanesque style with (if you look carefully) gargoyles. (Rumor has it one is fashioned to look like Bazalgette, but it’s hard to tell.)

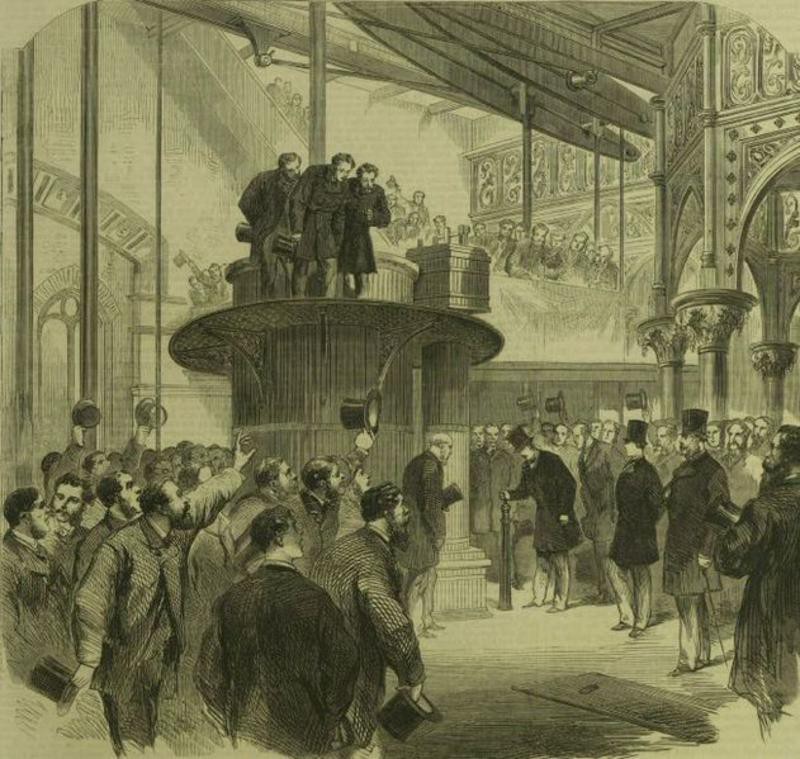

The complex was officially opened on April 4, 1865, by several princes, archbishops and the Lord Mayor of London. The invitation proudly declared that the site discharged 14,000,000 cubic feet of sewage daily.

At its center were four massive steam-driven pumps–named after the Queen, her husband, their eldest son, and his wife–which consumed 5,000 tons of Welsh coal a year as they pumped sewage into the reservoir before releasing it into the Thames.

When the pumping station was decommissioned in the 1950s, aspects of the complex’s underground parts were filled with sand and cement mix to avoid risks from flammable methane. When restoration work started in 1985, it involved excavating 100 tons of this sand. Rainwater had caused serious rusting of the engine parts, and the building had suffered decades of vandalism and decay. But the engines were still there. The scrap metal they contained wasn’t worth enough to warrant the cost of taking them apart. So, partly because no one cared, the bones of Crossness were preserved. Although there is a lot more work to do, some of its inital granduer has been brought back to life.

If you ever have a chance to visit, do. It’s very beautiful and eerily quiet because of the surrounding marshland. As much as London has grown since the mid-19th century, Crossness still feels far away from the central stink of the city. Bazalgette’s project, built for the three million Londoners of the 1850s, is still the backbone of the city’s sewage system today, servicing the waste of a population over eight million.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Metropolis section, on the way cities influence new ideas–and how new ideas change city life. Click the logo to read more.