Innovation need not always be high-tech to have impact. Inspired by nature, traditional crafts, and ancient technology, the folks at design firm Architecture and Vision (AV) created a stunning low-tech apparatus–the WarkaWater tower–that harvests water from the air.

Their goal? To ease Ethiopia’s water woes. For many rural Ethiopians, procuring water means a several-hour foot commute–often to questionable water sources leaving little educational time for the women and children charged with the task. After an eye-opening trip to the region in 2012, AV director Arturo Vittori set out to find a solution, soliciting input from locals, anthropologists, and the Ethiopian Institute of Architecture at the University of Addis Ababa (now a collaborator).

Wells built over the last two decades in some large villages have helped with water shortages, but their upkeep and location mean they’ve only benefited some. So instead of looking down, AV looked up. “Air always contains a certain amount of water,” Vittori said. This was especially true in the desert with the pronounced difference between daytime and nighttime temperatures–the recipe for condensation. Luckily, there was a local condensation-capturing expert on hand.

The Namib beetle lives in the desert collecting dew on its bumpy shell and funneling the water into its mouth. AV studied the beettle, as well as looking to prehistoric dew ponds and ancient Egypt’s condensation-capturing rock piles.

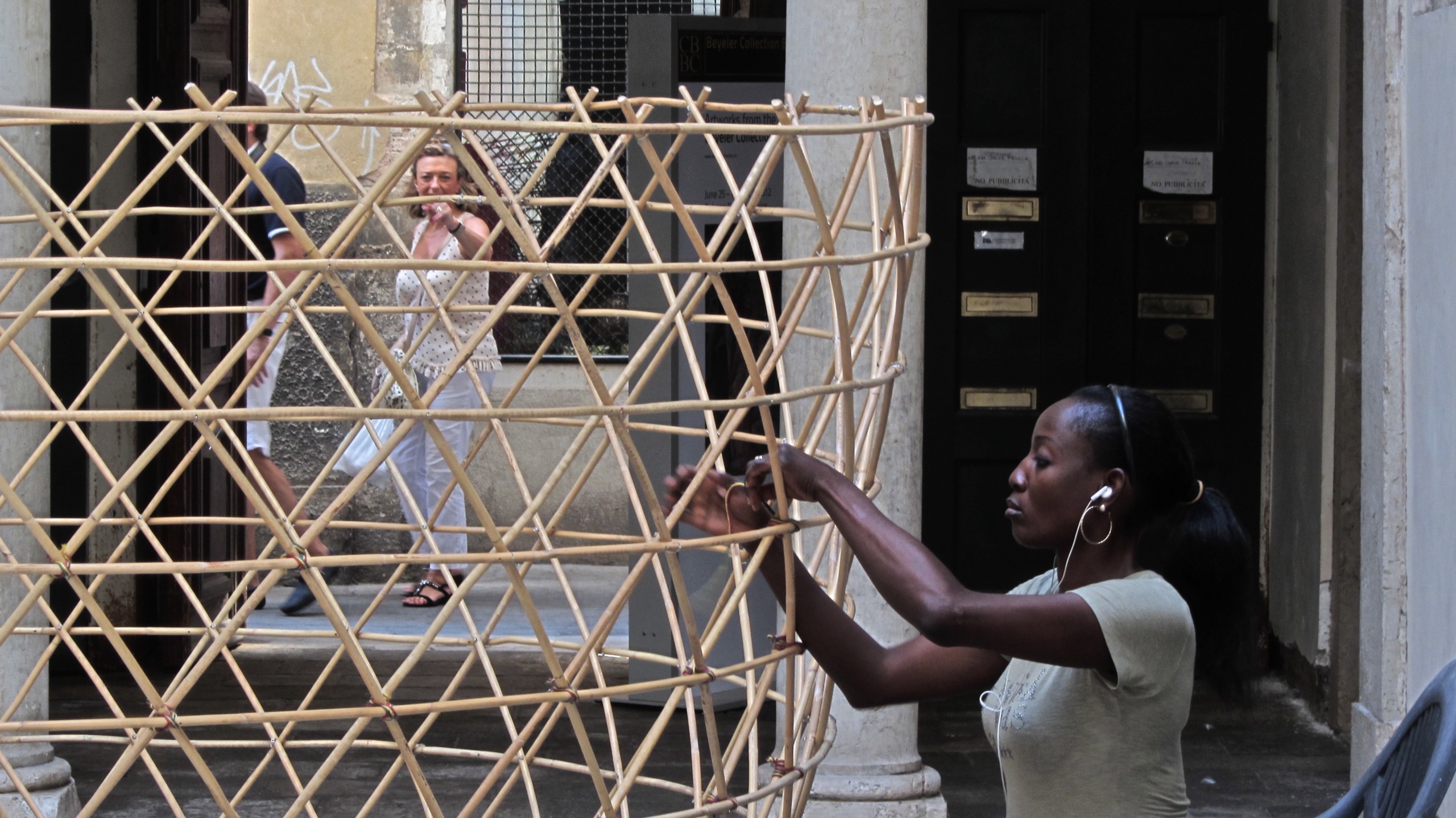

There were other design conditions: Materials would be local (like the junco mesh which collects the water) and low-cost (like the bamboo skeleton of the tower). Locals also had to maintain the apparatus without regular outside labor or specialized equipment. And the only way this would happen was by integrating the WarkaWater tower into daily life. “This is something we understood studying the culture and also talking to Ethiopians,” said Vittori.

The Warka tree, from which WarkaWater plucks its name, is a 100-foot-tall tree, and unfortunately one that is falling prey to deforestation. It serves as a shady gathering place for education, traditional ceremonies, and prayer. WarkaWater towers would follow suit as an alluring gathering place, with shade, solar-powered lights, and a design inspired by local architecture and crafts.

Two years and 10 prototypes later, the WarkaWater tower has evolved, but not without trial and error. “Sometimes we have good results. Sometimes bad,” Vittori said of the worldwide outdoor tests from Beirut to Brazil to Munich. “Daily research is very dependent on the weather and the weather is never the same. We are understanding the physics behind it, which is simple and not really simple at the same time.”

For instance, the shape and height of the tower, which attracts both rain and condensation, greatly influences water collection amounts. AV has tried several configurations. “Now we are on the version called 3.1, which has been the best of the results we have achieved so far,” Vittori said.

This prototype will be erected in Ethiopia in early 2015 and monitored for one year by local groups. Eventually, AV hopes WarkaWater towers might populate the landscape, each providing over 25 gallons of water a day. Because, as the project’s motto points out, every drop counts.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our The Future of Food section, which covers new innovations changing everything from farming to cooking. Click the logo to read more.