Your dog has it easy, right? Some days the fluffy thing’s life is flat out enviable. That’s why it’s not totally crazy to think that we might find ourselves becoming more like our pets soon enough–fed regularly and groomed by someone (or something) else. But before that happens, experts warn that our relationship with technology might change unexpectedly, even as we rely on it to live more comfortable lives.

Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak recently suggested that as AI gets more intelligent, we might see a power-dynamic shift–especially as “we want to be the family pet and be taken care of all the time.” He continued:

“Will we be the gods? Will we be the family pets? Or will we be ants that get stepped on? I don’t know about that “¦ But when I got that thinking in my head about if I’m going to be treated in the future as a pet to these smart machines “¦ well I’m going to treat my own pet dog really nice.”

While Wozniak was referring to large-scale, industrial AI, his pet analogy is a useful way of thinking about the more intimate relationships we have with devices we use every day. Might they become smarter than we expect?

We often start sentences with, “In the future, we will “¦ ” And when we do, we’re usually hopeful that this implies positive possibilities beyond our imagining. But it might be the opposite. We could increasingly feel trapped, not helped, by assistive technologies. After all, not everyone sees the affordances, helpers, and time-savers promised to us in the near-future (“smart” everything, from clothing to health to homes) as wholly desirable or benevolent.

I was reminded of this a few weeks ago as I watched Anab Jain of Superflux give her keynote at Next15 in Hamburg, Germany. Discussing her perspective on the theme of the conference, “How Will We Live?,” Jain sketched scenarios that stopped far short of optimistic, “in the future, we will”¦” propositions. She showed scenes from Uninvited Guests, a short film by design firm Superflux. It imagines how assistive devices could actually disrupt the lives of the elderly for whom they are designed to help.

In the film, an older gentleman is provided with a number of assistive devices, one of which is a “smart” cane that prompts him to get out and log a certain number of steps, with no regard for his personal interest or desire in walking from day to day. When he decides not to walk, he “hacks” the interaction by passing the cane along to a young neighbor, who racks up the required number of steps and is then rewarded for his help in deceiving the AI.

While the smart cane’s intention might generally seem good and healthy, its inflexible programming robs the user of autonomous decision-making and the capacity for determining his own actions. The cane doesn’t become smarter than its owner, but it does demand that the owner’s behavior change to fulfil its programming. Just as in the case of a pet, the owner learns, then adapts to satisfy the cane’s expectation for documenting a certain number of steps each day. Unlike your dog, though, the man is able to use a “hack” that avoids the benefits he’s meant to get from it.

The more devices the owner has, the more he alters his behavior to pretend to comply with them. He rearranges his life to satisfy their metrics. Ultimately, those devices end up working for his distant family members but do nothing to improve the quality of life for the elderly man they’re “caring for.” The important question here becomes: if the man had seen the cane as a reliable and loyal companion, like a pet instead of an interloper, would he not have tried to trick it?

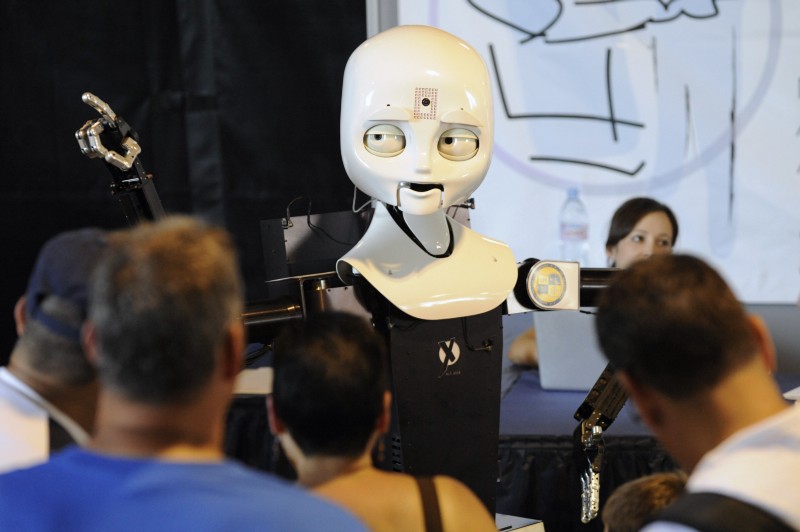

The marketplace of ideas for improvements in the lives of the elderly and disabled is heavily populated with machines intended to support individuals in need. Unfortunately, more often than not the end products seem designed mostly to relieve a family member or caregiver of responsibility for particularly time-consuming, emotionally stressful, or intimate tasks. This bias toward the needs of the caregiver sometimes leads to one that promotes a robotic presence or artificial intelligence as a replacement for human interaction and support.

Even in countries like Japan, where helper robots are relatively commonplace, many people register a strong level of discomfort and suspicion around robotic or AI interfaces. For the elderly and disabled, these “smart” products might represent the threat of something sent to take away personal autonomy. One person’s support device is another person’s robotic overlord.

If we think about the relationship of a pet with its human companion, it often involves two-way learning. A puppy comes with no knowledge of its intended home; then, over time, it learns and adapts its behaviors to accommodate its surroundings–but only to the limits of its individual intelligence. At the same time, the pet owner learns how best to communicate with, train (to an extent), and coexist with the pet. There is a symbiotic relationship between pet and owner–it’s not a master-servant arrangement.

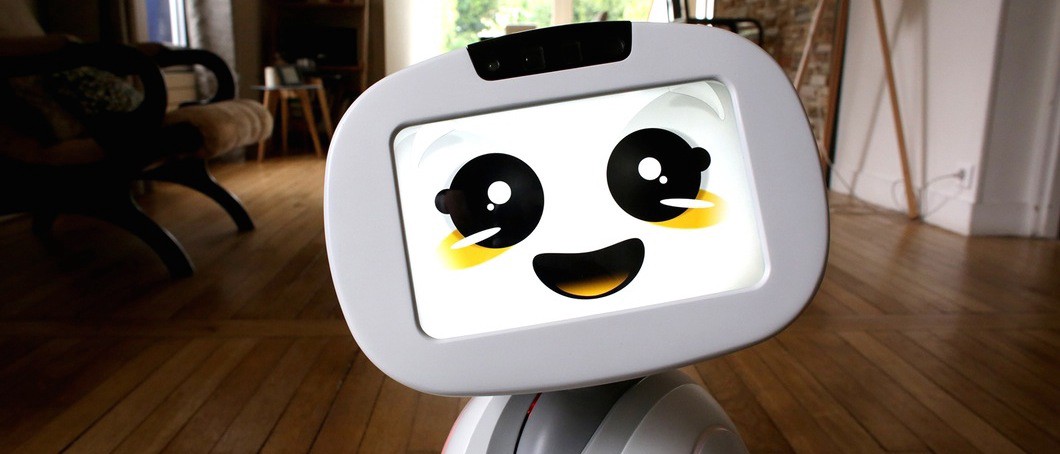

A lot of research has been conducted into robots as companions over the last few years–and the findings have been quite positive. Some even suggests the likelihood of robotic pets in the future. What we can learn from this research, in terms of assistive devices, should be acknowledging the importance of creating a positive, social relationship between an assistive device and its user–even a physical and emotional connection. With this ideal in mind, future assistive devices could be designed to bridge the perception gap of robots as non-feeling or non-intentional objects. Fortunately, when programmed correctly, some AI is already very adept at adaptation and learning to express emotion.

A different way of looking at the problem involves reframing the question of an individual’s needs and relying more on identifying his or her abilities, instead of just his or her disabilities. It seems that focusing on understanding the degree to which a person can take responsibility for themselves, then providing only as much support as is required (or desired) leads to better outcomes for everyone involved. In this way, AI becomes a very useful tool for establishing a general base of knowledge. When coupled with interactions over time, this combination should lead to an adaptive support model for championing an individual’s long-term mental and physical health.

Adaptive programming isn’t the only key to more trust between AI and humans. Imagine, for example, if a smart cane were transformed into a leash and attached to a miniature Boston Dynamics Spot robot pup. Spot, attired in an appealing outer covering; guided by AI programming; and fit with the standard-issue gyroscope for stabilizing balance, LIDAR, and stereo vision sensors, might integrate rather seamlessly into a person’s life. Now imagine it can talk, thanks to a Markov generator or Bayesian model for bot language acquisition. A truly assistive robotic pet that encourages its companion to exercise, take some downtime to rest, and prompts personal care and regular food intake might elevate its owner to a much better standard of living than devices that rely on static metrics and compliance reporting. Essentially, devices might be best developed following a service-animal model.

To address Wozniak’s concerns, “in the future, we will”¦” be best served if we treat our pets–robotic, AI assistives, or real–nicely. Hopefully, with the right approach, they’ll return the favor.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Robots vs Animals section, which examines human attempts to build machines better than nature’s. Click the logo to read more.