British spies maintained a secret exhibition hall to show off the tools of their trade during the Second World War–and it was hidden inside London’s Natural History Museum.

The wartime Special Operations Executive (SOE) used the series of sealed rooms, known as Station XVb, to exhibit its secret inventions–everything from an incendiary briefcase that could ignite to destroy documents inside it to the “Sleeping Beauty” submersible craft. Britain’s wartime Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, established the SOE in 1940″”75 years ago this July–to carry out clandestine operations behind enemy lines.

Duncan Stuart, the former SOE adviser to the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, explained: “The point of Station XVb was as a demonstration room. It was rather like a supermarket where you could go and see what was available in terms of equipment for your clandestine operations.”

Stuart continued, “It was also, to some extent, PR, but on a very secret level. Somewhere that VIPs, people like the King or the Queen, or ministers involved in clandestine operations could be brought and shown around.”

There isn’t much on record about Station XVb; while many of its items are discussed in the Secret Agent’s Handbook of Special Devices, it’s only mentioned in passing in a London travel guide. The best record of its existence is a collection of photographs kept at the National Archives in Kew.

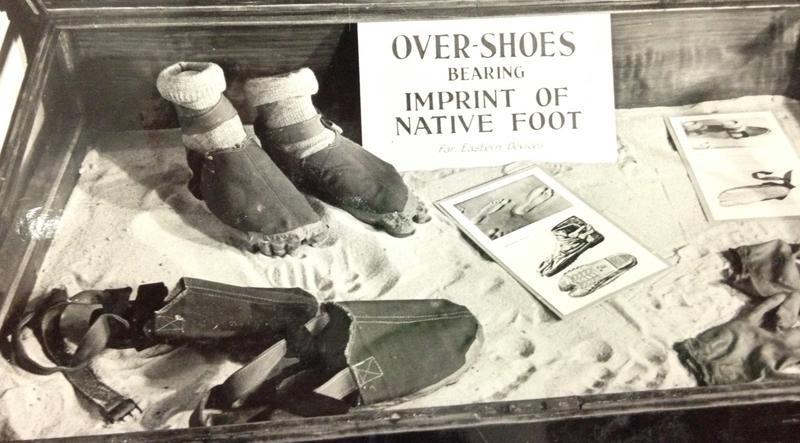

Given SOE’s remit, large parts of Section XVb were given over to painstakingly realistic disguises, including continental shoe styles and foreign-brand cigarette packets and matchboxes. Many of the clothing items were fashioned in workshops in the basement of the Victoria and Albert Museum across the road.

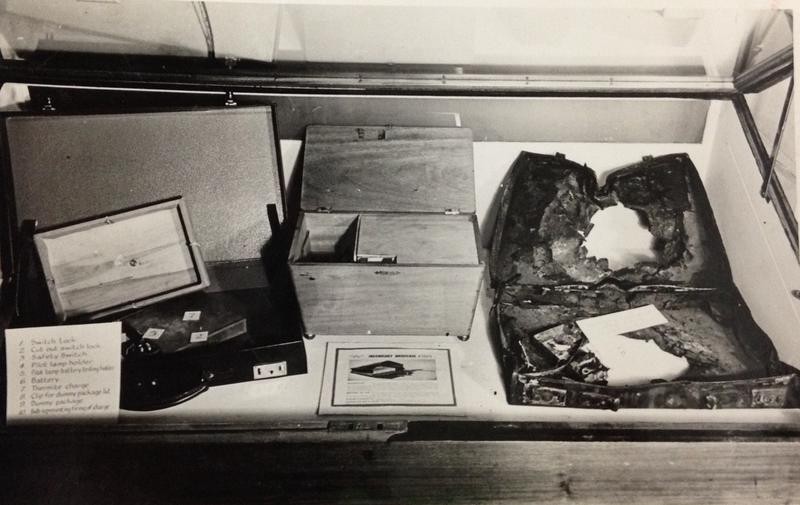

Likewise, disguising items for delivery in the field was a particular focus. “There were concealing-devices for various explosives, equipment, or food,” said Stuart. “Plaster logs or plaster vegetables–various items that you could put on the back of a farm cart and cart around France.”

Explosives could be disguised in any number of ways, some more convincing than others. One of the most effective, at least psychologically, was exploding coal: designed to be hidden among coal used in the trains on the enemy’s railways. “These really scared the Germans when they found out about them,” Stuart said.

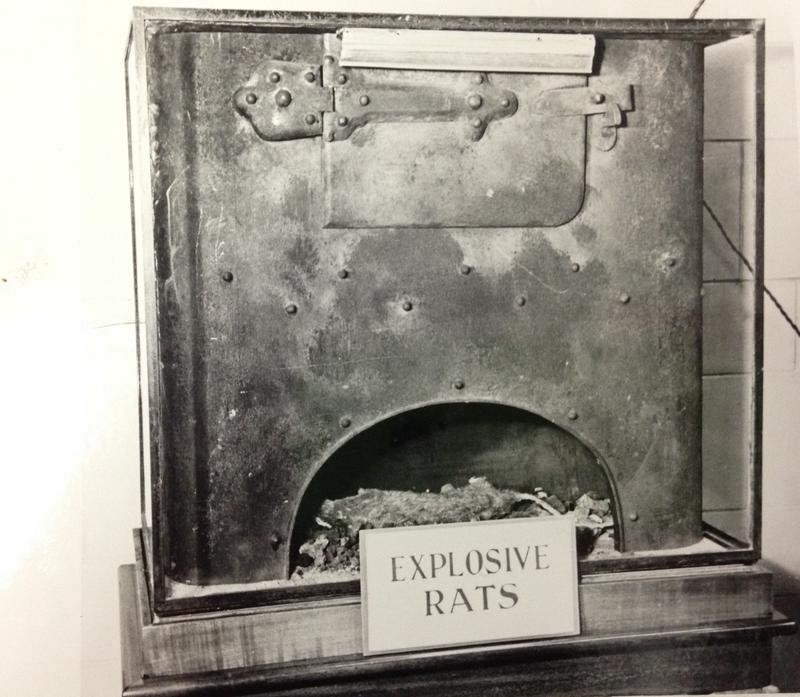

But there were other, possibly less successful variations, too. The photographs at Kew show an exploding imitation rat, bottles of Chianti, and oriental figurines, as well as an exhibit of exploding animal droppings–offering donkey or camel varieties, depending on where a soldier was deployed.

Alongside these were more ambitious inventions, generally produced outside of London in Section XV itself, a location known as “The Thatched Barn” on the Frythe estate near Welwyn in Hertfordshire.

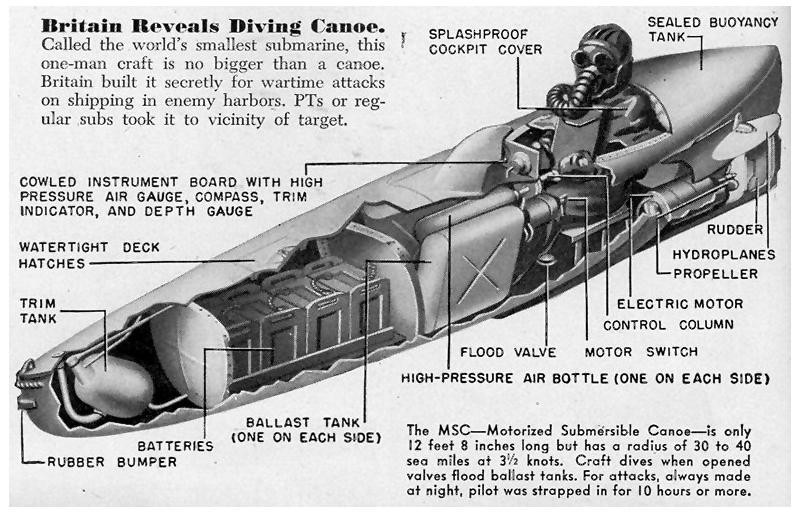

One such invention was the Welman submarine, a 20-foot-long, one-person submersible craft. The Royal Navy and the Special Boat Service were initially impressed by it, but the Welman sub was difficult to pilot. It didn’t have a periscope and by all accounts didn’t always surface the right way up. Consequently, it fell out of favor.

More successful was the Welbike, a small and easily assembled motorcycle with a two-stoke engine. It could be fitted inside a parachute container about four feet long for delivery to agents in the field. And it went on to become the prototype for the Corgi motor scooter, which went into production after the war.

Pride of place, however, was a battery-powered submersible canoe known as “The Sleeping Beauty,” designed by Hugh Quentin Reeves, one of the SOE’s most prolific inventor-engineers. At about 13 feet long, it was the world’s smallest submarine, and its pilot had to wear diving gear for when it went underwater. Its nickname supposedly came about after an officer found Reeves asleep inside his invention.

Finally, for sheer comedy, one of the most appealing of SOE’s inventions on display at Section XVb must surely have been the “over-shoes bearing imprint of native foot”–an item that may have confused the enemy by leaving behind faulty footprints, but had to have amused any agent equipped with them.

While only 16 percent of London’s Natural History Museum is actually open for pubic viewing today, even less was available during World War II. Now we know why.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Histories of”¦ section, which looks at stories of innovation from the past. Click the logo to read more.