It’s the evening of the 6 launch. But in South London, people are more interested in an old, broken vacuum cleaner.

At a Restart Party, hosted by the local Transition Town group at the Mushkil Aasaan community center in Tooting, aged electronics are matched with a volunteer fixer–”restarters” as they’re called–to see if something can be done. No one is selling anything. If anything, it’s the opposite: The idea is to make a fix, instead of buying something new. In the process, people are reconnecting with technology, and connecting with each other, too. And it’s an inspiring thing to witness.

Here, local people are queuing up, clutching a range of domestic devices: cameras, radios, phones, hair dryers, hair-straighteners, a toaster, a coffee grinder, a Hoover, toys, keyboards (computer and musical), PCs, DVD players, the receiver the community center uses to hear the call to prayer from its local mosque, and more. Some of these devices arrive carefully repacked in their original boxes. Others dangle from their owners’ wrists in plastic bags. Several are hidden in pockets or handbags–most electronics these days are designed to be carried around on your person after all. One guy arrives hugging his TV, though. It looks odd. But it was too big to fit in a suitcase.

At a desk near the door are Janet Gunter and Ugo Vallauri, who founded the Restart Project in 2012, building it into a global movement. They inventory what people have brought, catalogue the issues, and connect them to a restarter who will try and help. On the table in front of them are Restart Project leaflets; some Transition Town papers; and a pile of DIY wonder material called sugru, a self-setting rubber that bonds to nearly anything and hardens into strong but flexible silicone overnight. A notice reminds participants that “the most ethical mobile is the one you have already.” Under a logo of a spanner in the middle of a circle, we’re told, “Don’t despair, just repair.”

The political dimensions of the Restart Party aren’t overt, but they are there. A representative from the Gaia Foundation has a tabletop to share its work on the environmental and human costs of the phone business. Modern gadgets, it argues, may look space-age and sleek, but they ultimately come from the earth and were made by people, exploiting both. This seeds conversations about the ecological impact of these bits of technology we carry around with us, and how they are connected to people and places across the world. Attendees seem to want to talk about these issues anyway, even if an activist hadn’t been there. It’s part of the process of opening up and looking afresh at the devices.

Still, people attend restart events for different reasons, Janet explains. “Some people just can’t afford to get anything new. We’ve had unemployed young people tell us, “‘If I can’t fix this laptop, I can’t apply for jobs.’ But we have people who just don’t subscribe to the idea of throwing stuff away, and people who simply love tinkering. It’s a real mix.”

The restarters are mixed, too: former professional repairers, a lot of IT people, one guy who works in a guitar repair store, a school lab technician, another with a background in set design, retired folks. Some are women, too. The Restart Project is actively working on the gender balance, running a few female-only events. “Maybe I’m biased but it’s not a machista space,” Janet says. “There is very little grandstanding and bravado. Fixing is not a hostile environment for newcomers.”

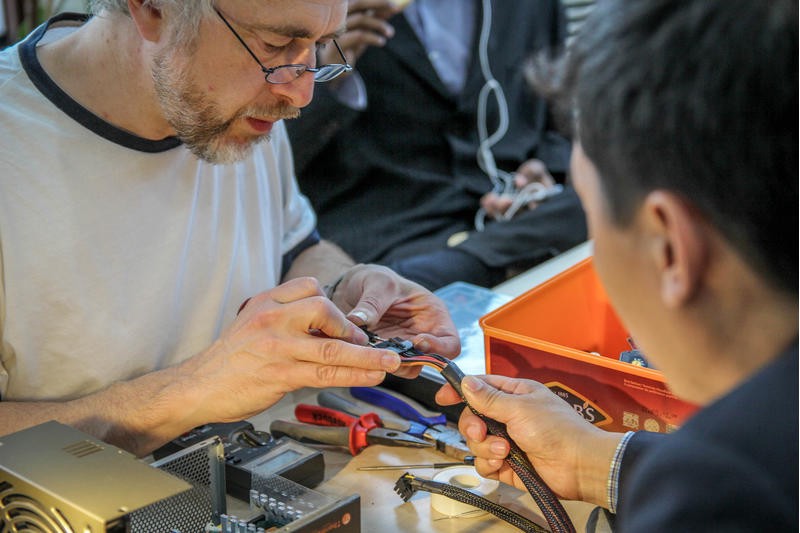

As screwdrivers come out, spotlights go on and wires are exposed, there’s something slightly medical about the whole thing. The seats are set up a little like a waiting room. Janet and Ugo act as triage at the front. There is a process of diagnosis, discussion and treatment, and a similarly uncomfortable sense of managing a range of limited amounts of expertise. A bit like when you visit your general practitioner because you have an odd rash. Sure, the doctor knows more about rashes than you do, and what to look for in terms of common ones, but won’t necessarily know exactly what’s up with your particular ailment.

While the restarters vary in their approaches, they all tend to explain, ask questions, and require that the person with the problem do a fair bit of the work. They’re not wizards. It’s a matter of puzzling it out, and involving everyone in the process. They use laptops and phones–working ones, not those there to be fixed–to download manuals and trace information about different devices. The crowdsourced repair guide iFixit helps at times, but not always. Restarters often have to look up not just the device in question, but trace components, too. There’s also an element of “just opening it up and having a poke” to see what happens, a journey of discovery people seem to enjoy for its own sake.

As Janet tells me later, “Even when we don’t fix stuff it’s a huge learning opportunity. Also, it’s just fun.” You get to see a bit of the world that’s normally closed off. “People feel empowered,” she says. Dave from the Transition Town group laughs, “I thought they’d be experts, but [my restarter] says he does it by trial and error.” I see a toaster taken to bits. Every now and again the restarter gives the base of it a bash. Crumbs and screws fall out, ever so slightly like a cartoon.

Also, there is a fair bit of swearing. “Er, okay, let’s pretend that didn’t happen,” mutters a restarter named Rob, as he tries to fix a camera flash. “This is going to be fun to get back together,” he then sighs ironically, before the owner of the flash has the ingenious idea of using the camera to take a photo of each step so they can be retraced visually. “There are a million things that could be wrong, in a million places,” Rob says.

He and the camera’s owner ultimately diagnose the problem in one of two possible areas and decide to dig deeper into one of them. I ask if it’s part of the fun–the digging deeper. “No, no, no,” Rob replies swiftly, “nothing about this is fun.” He buries himself further into the problem, fashioning a smaller pair of pliers with a paper clip. I don’t believe he’s not enjoying it.

Fun of the puzzle or not, the confusion people are feeling reflects the price we pay for the many advantages of modern technology. Complexity offers power, but with it comes a lot of alienation. The difficulty the restarters face is in no small part, because a lot of these devices aren’t made to be fixed. Some manufactures are open with their service manuals, but others actively keep them hidden. In the case of one of the TVs brought to the event, breaking it is practically a requirement to get inside.

And yes, deeper diagnosis can get emotional. “Ooo, I’m going to have to look away,” one participant exclaims as the top is taken off a computer. Sure, many of these objects are expensive, so there is a feeling of risk. But moreover, they also reflect our most intimate relationships. We use phones several times a day as mechanisms through which to interact with our friends and family. Televisions project dramas that make us cry and laugh. Toasters, kettles, and other food gadgets help us feed ourselves. These black boxes sit at the core of our lives.

So logically, there’s some sense of transgression when opening and laying them bare. Talking to Janet later that week, back at her office space in Somerset House’s Makerversity, she says, “A lot of the stuff people take to us is out of warranty. They’ve got nothing to lose. And yet, that little warning at the back is enough to put them off.” She explains that while the restarters follow safety guidelines and try to reassure people, “There is a real culture of fear of opening stuff up. They need permission. So we give them permission.”

One of the striking features of the Restart Party is the social space it creates. Several people pop in just to see friends even though they haven’t anything to fix. But many are totally new, drawn in by the chance to solve a problem, or attracted by the commotion they can see through the windows. It’s a local community event as much as it is a tech one. There’s hot tea and biscuits, and samosas fresh from High Street. There are hugs over the circuit boards, gossip, and flyers handed out for a food festival the following weekend. In the midst of all this, people share stories about the objects they’ve brought along; what that old kettle means to them, who bought them that camera, how much they need that computer. (The oldest was probably a vacuum cleaner from 1990, farther along in years than some of the people at the event.)

When the topic of the Apple launch comes up, someone notes, “When they make a fixable one, then I’ll be interested,” asking rhetorically, “When are they going to offer that?” There’s a lot of moaning about how quickly devices break, and how helpless we as customers feel when this happens. This is an area Janet and Ugo are keen to develop. They want to use Restart events to collect data to take to manufacturers. “They know things are breaking, but what they don’t know is how frustrated people are, that they’re looking for repair opportunities,” says Janet.

It’s going on 8:30 p.m. when Janet calls out, “Hey, everyone, we have 30 minutes, so don’t do too much more disassembly.” She grins and turns to me and one of the Transition Town hosts. “Some of these people are maniacs. There is no stopping them,” she says.

And with the whooshing sound of a once-broken hair dryer now working again, someone’s going home with a device they don’t need to replace.

Thanks to Transition Town Tooting and the Restart Project for letting me drop by. Let the Restart Project know if you want to host a Restart Party. You can also invite some of the Restart Party magic into your workplace.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Design & Innovation section, which looks at new devices, concepts, and inventions that are changing our world. Click the logo to read more.