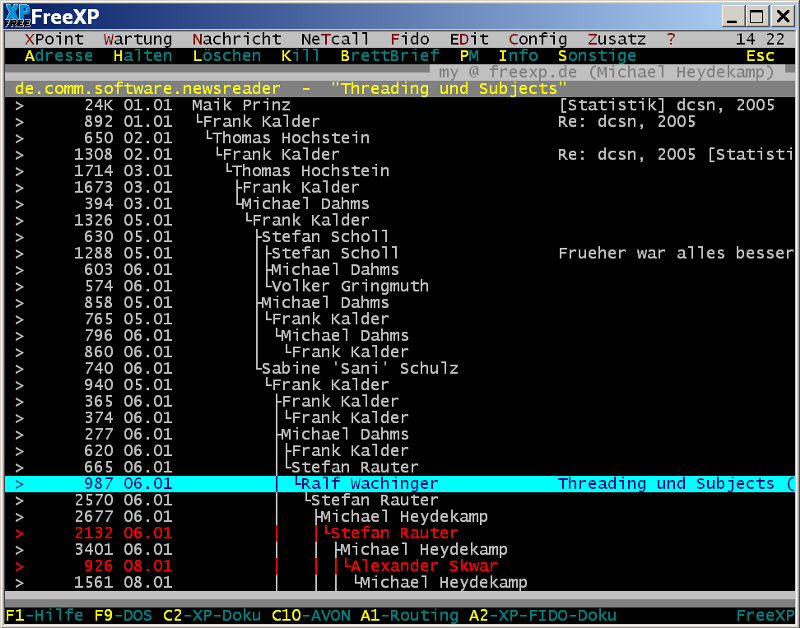

The first commercial spam message was sent in 1994–or at least that’s the general consensus. Lawrence Canter and Margaret Siegel had a program written that would post a copy of an advertisement for their law firm’s green card lottery paperwork service to every Usenet news group–about 6,000 of them.

Because of the way the messages were posted, Usenet clients couldn’t filter out duplicate copies, and users saw a copy of the same message in every group. At the time, commercial use of internet resources was rare (it had only recently become legal) and access to Usenet was expensive. Users considered these commercial-seeming messages to be crass–not only did they take up their time, but they also cost them money.

In reaction to the “green card” incident, Arnt Gulbrandsen created the concept of a “cancelbot,” which compared the content of messages to a list of known “spam” messages and then, masquerading as the original sender, sent a special kind of message to “cancel” the original message, hiding and deleting it. Two months after the original spam postings, Canter and Siegel did it again–upon which the combined load of spam and cancel messages crashed many Usenet servers. Anti-spam measures, it seems, had themselves become spam.

While this was the beginning of commercial Usenet spam, this was not the beginning of Usenet spam in general. Prior to April of 1994, a poster known as Sedar Argic would automatically reply to any message containing the word “turkey” with a lengthy rant denying the Armenian genocide. This, of course, made discussions of Thanksgiving celebrations difficult.

The thing about all of these early forms of Usenet spam is that the messages were always identical. Cancelbots worked because the messages they were canceling were either identical or changed very infrequently–they could be compared to a human-maintained list of spam messages (a “corpus” of spam).

But even during this era there were Usenetters using a new technology that would upset this and future countermeasures: Markov chains, which are a popular tool among modern bot-makers. Invented in 1913 by Russian mathematician Andrey Markov, a Markov chain works by combing through text, looking at which words tend to follow each other, and assembling new sentences, paragraphs, and pages using the resulting statistics. Want to try it? Here’s a website that generates filler text from Shakespeare, Jane Austen, the Nixon Tapes, college essays, and even the Bible.

It didn’t take long for spammers to realize that cancelbots could be stumped by adding random junk to the end of messages. At the same time, spammers were moving beyond Usenet into email, just as regular people all over the United States and western Europe were suddenly learning what a modem was and signing up for web access.

By this time, people dedicated to identifying and fighting spam (a problem that had barely existed six months earlier) had already started creating “honeypot” email accounts. These were accounts that no human being would have any reason to send messages to, created for the purpose of accumulating a large corpus of spam, with the goal of researching spammer behavior and developing new spam-fighting techniques. With so many spammers carrying different messages, and random junk being newly added to the end of messages (or beginning, or middle), spam-filtering technology had to get smarter. Programmers began to look at word statistics and Markov models to identify the spammers.

But spammers quickly figured out that they could use the same Markov chain technology against the filters: By creating Markov chains out of clearly non-spammy material (usually derived from Project Gutenberg, a collection of out-of-copyright e-books), spammers could add legitimate-sounding but nonsensical phrases to the end of their messages, making the job of the filters harder. That technique is called “Bayesian poisoning” and is the origin of spam poetry.

Unfortunately for spammers, Bayesian poisoning tends to make messages too unconvincing: Long strings of unrelated words don’t sell. But there’s another way to get around blacklists based on a corpus of text–a technique that became all too common when people started including comment sections on the nascent web. In the spam community, it’s called “spinning.” The rest of us know it as “generative grammar.” Spinning uses variations on phrases in an existing message to create large numbers of semantically identical but distinct messages. Like Markov chains, it’s popular within the bot-making community, and you can try it for yourself here.

Shortly after email and web browsing became the norm, instant messaging followed. While chat services date back to the early 1970s, large-scale internet-based chat systems like IRC appeared in the late 1980s. As people started growing up with internet access in their households, commercial services like AOL Instant Messenger boomed in popularity.

On IRC in the 1990s, a lot of what had happened on Usenet repeated itself. People wrote Markov chain bots for amusement; other people wrote bots to paste pre-written diatribes in response to particular keywords. Some spambots existed that posted advertisements automatically. But the IRC community, like Usenet, quickly developed technical countermeasures.

Commercial instant messaging services, on the other hand, skewed young and nontechnical. Whereas IRC and Usenet were used and run mostly by programmers, AOL was targeted toward families. When bots appeared on AOL Instant Messenger, AOL had no incentive to stop them; when bots began sending misleading messages to AOL users, the company didn’t have enough experience with spam to be cautious of where this might lead.

Meanwhile, some AOL bots like SmarterChild and GooglyMinotaur were officially sanctioned. Despite the commercial angle, these bots wouldn’t message people without provocation and, thus, arguably were not spambots. Still, their underlying technology was identical, and their attempts to act human represent not merely a precursor to similar systems like Siri, but also a less sinister version of what instant messaging bots at the time did to trick naive teenagers.

If you’ve ever used Twitter, many of the spam techniques I’ve mentioned above will be familiar. You already know that users who post links only are unlikely to be human, particularly if they have a supermodel avatar. At some point, you’ve probably inadvertently mentioned some buzzword (iPad, Bitcoin, etc.) only to be swarmed by tangentially related ads.

Other applications of these spam techniques on Twitter, however, are more interesting. Some, like RedScareBot, are subversive. Others, such as StealthMountain, are educational. Some use normally questionable time-wasting techniques for the greater good by redirecting abuse–such as an ELIZA implementation that engages people using Gamergate-related tags, causing naive trolls to flame a bot rather than a human.

But there are many other modern use cases for these technologies, too. In the academic world, in response to a series of scandals related to fraudulent conferences, a tool called SCIGen was developed that used spinning to generate nonsense papers as a way of ensuring that journals and conferences were doing peer reviews. In 2014, IEEE and Springer, two major academic publishers, adopted the use of a tool for automatically detecting nonsense papers generated by SCIGen after it was revealed that more than a hundred such papers had gotten around peer reviews.

In 2010, Amazon opened its eBook store to self-publishing only to be flooded with e-books made automatically by web scrapers. While content farms for clickbait sites are mostly run by poorly paid humans, The Associated Press is using spinning techniques to generate sports and finance articles, and others are building bots that can write clickbait.

What this all leads to is unclear. Science fiction author Charlie Stross suggests, in his 2011 novel Rule 34, that the competition between spam and anti-spam technology might drive forward future AI research. In his novel, a superhuman AI evolves from an experimental spam-filtering technology and, as a side effect, has no internal sense of self: It projects its consciousness on some arbitrarily chosen user, because its intent is to determine what that user would consider spam.

Hugh Handcock, another science fiction author, suggests in a recent blog post that the future of chatbots may have more in common with the spambots and mass-trolling of Anonymous and early-1990s IRC than with Siri. Chatbots, by design, might be more desirable to interact with than humans are–they could perpetuate rather than break down filter bubbles, becoming something to interact with without ever leaving one’s comfort zone. They might swarm around dissenting opinions. Handcock presents a world in which a human might know that all his friends are bots trying to sell him something–and simply not care.

Meanwhile, 1990s virtual reality pioneer Jaron Lanier, in his 2010 book You Are Not a Gadget, presents his concerns about current trends in publishing and media where the monetary value of artistic expression is tied to advertising. In his 2013 follow up, Who Owns the Future, he offers a possible end game for an advertising-driven society: one wherein physical spambots provide goods and services for free to people in their target market, while leaving everyone else to starve.

The second episode of the TV series Black Mirror, “Fifteen Million Merits,” dreams up a similar society–an economy based on the twin poles of entertainment and physical labor that extracts money from laborers and funnels it into the entertainment complex by using aggressive advertising that can only be accepted or dismissed using micro-transactions.

Lanier suggests that voluntary micro-transactions might be a way for artists to take back control of their work from the advertising industry and avoid an imminent fall of media from a middle-class to a lower-class position. The Black Mirror episode shows how as long as the entertainment industry is centralized, however, micro-transactions can be a tool for perpetuating class divides and systematically excluding people from participating in the creation and sale of art.

Personally, I suspect that with the new emphasis on conversational interfaces, we’ll begin to see hybrid spambots: Existing conversational interface systems like Siri and Echo, because they serve up data from third parties, might begin to be manipulated by some bot-equivalent of SEO to respond to certain queries with advertisements. In this environment, no automated methods exist for filtering out ads–and since conversational interfaces are often run by retailers, there is no incentive to do so. Rather than trying to outwit spam filters, the creators of these bots would need to be subtle enough to avoid alarming users.

As the landscape of the internet changes, and as countermeasures are put in place, one thing remains constant: So long as spambots can remain profitable, they won’t go away.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Talking With Bots section, which asks: What does it mean now that our technology is now smart enough to hold a conversation? Click the logo to read more.