Better technology in prosthetics, the branch of medicine concerned with artificial limbs, means that amputees can do more than ever before–while the technology enabling them to do so is increasingly on display.

The makers of the woven, carbon-fiber, blade legs used by amputee runner Aimee Mullins and others made no apologies for not following the design of human legs. The blade legs are modeled instead on the hind legs of a cheetah.

Similarly, some modern prosthetic arms–the Open Hand Project, for example, or Limbitless Solutions–are more reminiscent of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s hand in Terminator than a real human limb.

Emily Sargent, a curator at London’s Wellcome Collection, says modern prostheses are much more about what the user wants to achieve than a cosmetic replacement of what’s missing.

“You’re not trying to convince the world that the athlete who uses blade legs has a biological, human leg,” she said. “He’s got the prosthetic that best fits the purpose for which he wants to use it.”

One of the earliest prostheses, discovered in an ancient Egyptian sarcophagi and dating back to 600 B.C.E., is crafted in the shape of a big toe. Several of these have been recovered over the years and while it’s been suggested the toes were merely intended to complete Egyptians’ bodies for their journey into the afterlife, there are indications they could have been used during the amputees’ lifetimes.

In Europe, an artificial leg dating back to 300 B.C.E. made of bronze, iron, and wood was found in Italy in the 19th century. Also, in the 1500s the German mercenary Gotz von Berlichingen was known to have had an iron hand fitted after he lost his in battle, allowing him to continue his career as a soldier for years afterwards.

A major step forward in prosthesis design came in the early 19th century with the development of the Anglesy Leg, modeled for Henry Paget, the Marquess of Anglesy. Paget lost his leg when he was hit by a cannon ball at the Battle of Waterloo. In 1816, he had limb-maker James Potts craft him a device that could bend at both the knee and the ankle. He seems to have liked his new leg so much that he immediately ordered five more.

Some prostheses–such as the prosthetic noses once designed for those who had contracted syphilis–have been almost entirely aesthetic, but as far as prosthetic limbs are concerned, functionality has (understandably) always been important. Even if, at times, it has clashed awkwardly with concerns about appearance.

By the mid-19th century, prosthetics were an international industry–with a section of The Great Exhibition held in London in 1851 dedicated to the many companies involved in their manufacture.

As with other branches of medicine, major innovations in prosthetics have tended to follow major wars, a trend that continues today with the treatment of those returning from the West’s war in Afghanistan and the U.S.-led occupation of Iraq.

Back in the 1860s, the American Civil War resulted in an estimated 35,000 amputees and prompted an expansion in the U.S. prosthetics industry. That included the development of the Hanger Limb, a wooden leg patented by wartime amputee James Hanger, who went on to found a prosthetics company that continues to provide care to amputees today.

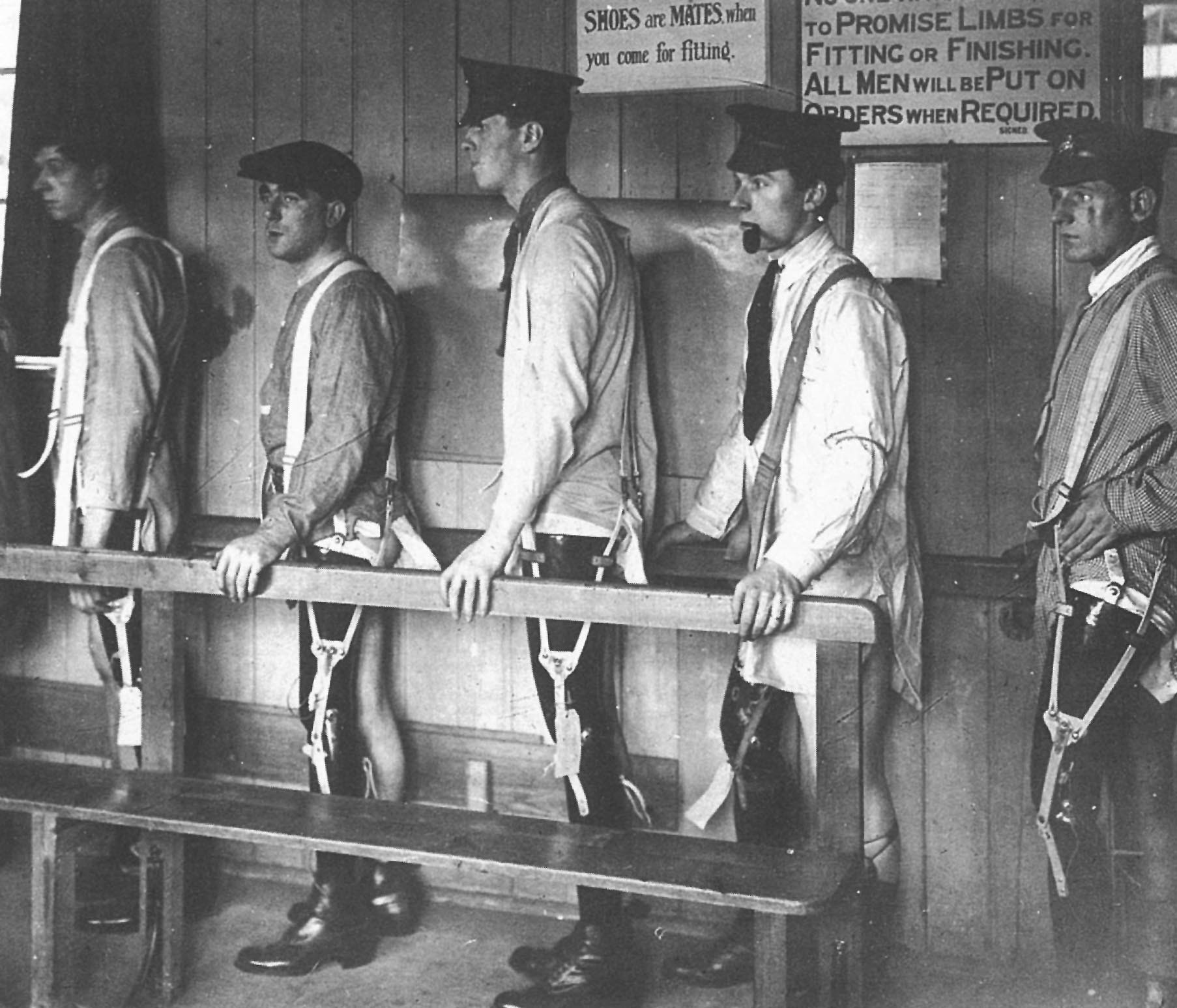

Europe witnessed a similar expansion at the beginning of the 20th century in the aftermath of World War I, when hundreds of thousands of wounded young soldiers returned home and tried to return to their normal lives.

For much of the 20th century prosthetic design was concerned with marrying form and function.

The focal point of Britain’s post-war limb-making industry was Roehampton Hospital in South West London. Limb-makers, including James Hanger’s company and the British firm Chas. A Blatchford & Sons, maintained workshops on the premises.

The most significant change in the post-war period was the adoption of assembly-line production for prostheses. Standardization and mass-production methods had been developed during the war largely because of the need to make weapons and ammunition manufacturing more efficient. Now those techniques were turned to the production of replacement limbs. In fact, in 1921 the government released the design for a standard military leg: a wooden leg that all contracted limb-makers would have to follow.

That same year also saw the development of certalmid, a material made from a mixture of celluloid, muslin, and glue, which could be manufactured quickly and became widely used in prosthetics.

The more durable material duralumin, a lightweight aluminum alloy used in aircraft manufacturing, was also gaining popularity in the industry at about the same time. Its first use in a prosthetic limb was by a British company, the Desoutter Brothers, in 1913. André Marcel Desoutter, who formed the company with his brother Charles, had lost his leg in a flying accident that year.

Innovation around the materials used for prostheses made the limbs themselves lighter. Advances in the 1970s and 80s came with the development of carbon fiber, greatly reducing the weight of the limbs and, as such, the energy an amputee expended by operating them.

At the same time, limb-makers became less concerned with copying human limbs, at least in terms of appearance. Microprocessors today can simulate muscle movement. So, for example, a prosthetic leg with a hydraulic ankle can be controlled to provide assistance when going uphill and act as a break when coming back down, but the limb itself need not look like a human leg.

Mullins, the amputee runner, has a pair of lifelike silicone legs; but as she demonstrates in her talk “It’s Not Fair Having 12 Pairs of Legs,” she also has many others that look radically different.

So, as the emphasis shifts from form to function, is it realistic to imagine the disabled could become the super-abled?

Professor Saeed Zahedi, the head of research and development at Blatchfords, which has been producing prosthetic limbs for more than 120 years, advises a dose of skepticism on this point. “For certain individuals you may find the application of advanced technology can allow someone who is disabled to perform better [than others] at “¦ running in a straight line for 100 meters,” he conceded. “But unfortunately you don’t live your life as a 100 meter sprint.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Vital Signs section, on the future of human health. Click the logo to read more.