Read the next installment: “The Future of Food, As Seen From Puerto Rico”

Read the previous installment: “Growing Food To Rebuild Puerto Rico”

All photographs by Mariángel Catalina Gonzales. Para leer una versión de este texto en español, haga clic aquí.

The community garden Huerto Semilla began at the University of Puerto Rico’s Río Piedras campus during the student strikes in 2010. Students were protesting changes to policies and tuition increases; they also demanded guarantees that the university system would not be privatized. Río Piedras is one of the largest of the island’s 11 public university campuses. While two of these campuses focus on agriculture, there is no agricultural curriculum at Río Piedras, nor any faculty members there who specialize in the subject.

“On this campus, there was no one talking about food prices or how to produce food on the island,” says Crystal Cruz, who’s been working at the garden since 2016, after participating in the island’s 2015 March Against Monsanto. She was inspired by the knowledge that, with proper organization and know-how, the territory could produce food year-round. “That’s when I decided I wanted to be out of the classroom and working on a farm.”

The small garden began as a way to incite discussion around the colonial dependence on imports, and especially about the vulnerable position that the island would be in if the supply were cut off. All the gardeners are volunteers; half are connected to the university in some capacity, while the other half are part of the wider community. Huerto Semilla has 18 growing beds, each 20 feet long and 2 feet wide, located on what was once a tennis court. “We have not only been farming food, we have been farming soil,” Cruz says, explaining how the gardeners use compost to add nutrients back into land that has been treated harshly for years.

Decisions about what to grow are made collectively. “It’s active organizing,” Cruz says. “All the materials, all the tools that we have, all the seeds that we have, we have because either one person from the garden had it at home, or people after [Hurricane Maria] started to donate to the garden as individuals.” Volunteers also earn money for supplies by providing composting services to the university and Comedores Sociales, a group that distributes food to communities in need; Huerto Semilla sells some of its crops to the organization as well.

After each brigade, or farm work session, every volunteer is served a plate of food made from the gardens’ crops, and they can go home with some of the harvest. While the initiative doesn’t provide enough food to supply a farmers market, its existence at the university serves to demystify and destigmatize farm work among a young population that often does not have access to Puerto Rico’s full agricultural history.

There’s a great deal of murkiness around what crops can be considered authentically Puerto Rican. Centuries of colonial rule and corporate agribusiness–especially Monsanto and their genetically-modified seeds–have separated most Puerto Ricans from the island’s agricultural history. And after Hurricane Maria, says Pao Lebron, an organizer for the Queer Trans Solidarity and Service Brigade, many seeds were sent to the island to replant, further complicating the authenticity question.

The Service Brigade spent months restoring farms and putting on workshops post-Maria, helping to build agricultural sustainability. Lebron wants to grow garlic here one day; they explain that it’s a staple of the diet that was introduced by Spanish colonizers and is not currently grown on the island. They recall, “I went to the National Archives to find out about garlic, and they were like, “‘Why?'” The archives had information on coffee and sugar, the main cash crops, but no resources on who first cultivated the allium that heavily flavors every sofrito, the base sauce of the island’s cuisine.

Papaya has become plentiful, though, after the seeds were blown around in recent hurricanes. Sometimes it can be found growing in the lone patches of soil in paved parking lots. At supermarkets, it’s one of the only local products that’s always available.

Like papaya, iguanas, too, have become abundant–but for different reasons. The lizards were introduced as pets in the 1990s and subsequently released into the wild, which eventually led to iguana overpopulation. Now, on a small scale, they are becoming part of local cuisine.

Lebron points out that the reptiles “eat everything.” Iguanas have been known to subsist on produce that Puerto Ricans are growing for themselves. “Now they’re probably the most organic meat that you can eat here,” Lebron says. They attended an iguana hunting, processing, and cooking workshop as part of their work with the Service Brigade. Every part of the iguana can be used–even the skin, once dried, can be turned into leather.

While grassroots movements are shifting how specific communities relate to their immediate ecosystems, larger-scale projects are looking at Puerto Rico’s agricultural future as a whole. Research hubs like Frutos del Guacabo, in the coastal town of Manatí, study which types of produce will grow best in the island’s various microclimates.

“Chayote needs less sun and more water,” says Adrian Rivera, the son of Guacabo’s owners, Efren Robles and Angelie Martínez. That’s why the experimental farm and distribution center has given chayote seeds to farmers in the center of the island to cultivate; Guacabo then acts as a hub to bring the produce to restaurants for purchase. Root vegetables grow best in the central region–except for carrots, which, along with ginger and turmeric, do better on the coasts.

The first thing you see when you drive onto the farm is the market stand, where Guacabo sells products from 40 other farms around the island. Around the edges, they grow the purple pseudocereal amaranth, which serves as a natural pesticide and can be used as a colorful garnish or cooked like a grain. Bugs will feast on it rather than the tomatoes, like the one I bite into and dribble down my dress. Rivera sats, “You’re going to notice it tastes different, because most of the tomatoes you eat are picked when they’re green.” These are bright red, grown alongside bright orange sungolds.

Rivera walks me around to see the goats, rabbits, and chickens. He himself makes goat cheese, though he’s trained in veterinary sciences. Fresh gandules, or pigeon peas, grow on small trees here. Edible flowers, which are used in salads, bloom nearby. Guacabo grows different varieties of eggplant, as well as passion fruit and soursop. “Once it gets a little bit ugly, that’s the best point,” Rivera says of the latter, a spiky green fruit with creamy flesh. “You expect to pick it really green and perfect”–but no.

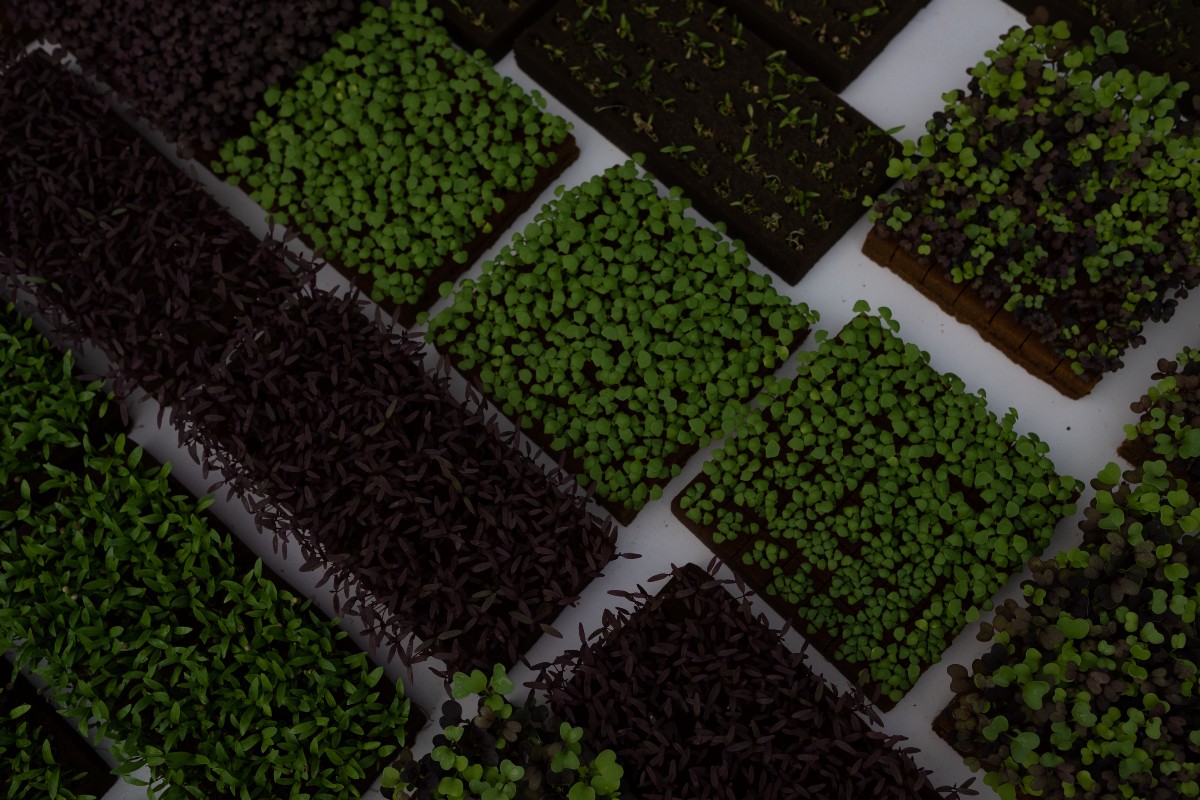

The farm hub grows micro herbs and lettuces in a large hydroponic system; the lettuce blend makes it to upscale markets, but most of their product goes to chefs and hotels. Rivera offers leaves of oxalis, telling me that my New York palate will taste green apple but that the taste buds of our Puerto Rican photographer, Mariángel Gonzales, will detect notes of the tropical cherry acerola. He’s right–something about it takes us both back to our respective childhoods. We are given bits of lemon drop, a yellow edible flower, which burst into our mouths in a sour assault, lingering on the edges of our tongues. We hold some of the small rabbits, though we’re told they’ll die in a couple of months. Meat, for restaurants.

Guacabo’s business model is restaurant-driven, because that’s where the highest volume of sales can be made. “The role of the restaurant is support. Cash flow,” says chef Juan José Cuevas when we speak the day after I visit Guacabo. He buys from the business on a regular basis, purchasing 30 pounds of whatever’s on hand and adding it to the menus at the Condado Vanderbilt Hotel. When he was a chef at Blue Hill, in New York City, he knew all the farmers providing him with produce; that’s what he’s attempting to re-create in his native home. “I knew their family, their granddaughters,” he says of the farmers whose produce he used to buy in the States, who he still visits. “Now, when I go, it’s a connection. It’s a family thing. You build that.”

Beyond restaurants, Guacabo has attempted to bring locally grown food to all of Puerto Rico. World Central Kitchen, the José Andrés-led charity that developed a massive presence on the island after Hurricane Maria, is inescapable at the farm–the logo is embroidered on uniforms and painted on buildings. An ongoing initiative through the nonprofit’s Plow to Plate program has funded territory-wide grants and produce purchases, which have bolstered agricultural efforts after many farms on the island were nearly decimated by the storm.

Guacabo is open to all who wish to visit, whether to purchase fresh produce, or to pet a goat, or maybe to nibble on a leaf that will take them to their own past.

Somewhere between the small university garden and the large farm supplying hotels with produce, midsize farms are also practicing agroecological techniques to produce more food. Josco Bravo, in the northern town of Toa Alta, provides training to new farmers and sells its own produce at a farmers market in the capital, San Juan. There’s Siembra Tres Vidas, in the mountainous municipality of Aibonito, and HidrOrgánica, based in Río Grande, east of San Juan.

The smaller farms have a relatively small presence at supermarkets, which means that access to their products is, for the majority of Puerto Ricans, minimal at best. “Since Maria, the interest in local agriculture has increased, but it’s still going to restaurants,” says Cuevas. “I think the turning point is going to be when there’s a combination, when the offerings can also go to regular people, to the supermarkets and farmers markets–a place where once or twice a week they can all go, that has good temperatures, and is easy for people to come in and out. But that takes time.”

PRoduce Home Box, a home-delivery service, is a new way to get local produce into the hands of household cooks. Co-founder Crystal Díaz, who works with partners Francisco Tirado and Cincosentidos Culinary Group, left a long career in marketing to build El Pretexto, a solar-powered culinary farm lodge in the mountains of Cayey. She invites chefs to cook dinners there, and hopes to eventually build out a farm; for now, at least, papaya trees line the driveway.

Díaz received a master’s degree in cultural action and management from the University of Puerto Rico, where she focused on how to connect local food sources directly with consumers. PRoduce has been the embodiment of her conclusion that a central hub would be necessary for the long term.

Home Box Recipients are sent a reusable container weekly or biweekly, filled with avocados, plantains, limes, lettuce, eggplant, squash, carrots, tomatoes, yams, and bread. Some weeks, there might be eggs, cheese, and fruits, too. Each bag is enough to provide a few meals for a family of four. But at $50 per delivery, the service is likely still too much for many Puerto Ricans, like the woman with the acerola I met in El Departamento de la Comida back in 2015.

“This is our 19th or 20th week,” Díaz tells me when I come to visit her at El Pretexto. It’s February, and we’re sitting at a table with the mountains in view, her two dogs at our feet. The surrounding land is lush; many people have told me that anyone visiting for the first time would never know the hurricane happened. “We’ve bought and delivered more than 20,000 pounds of locally produced food,” she says. “We buy from 40-plus different producers, all over the island.” The company employs 11 drivers to make deliveries to 240 subscribers.

The project was inspired by Martin Louzao, the chef behind Cincosentidos, who wanted to connect chefs with various local farmers. “It was very difficult to buy local produce in the amounts a restaurant would need,” Díaz says. “After it was born for chefs, we did a little pivot, because we realized that the purchasing power was all with the restaurants.” Now, PRoduce buys the produce itself, which allows the farmers–90 percent of whom Díaz says employ agroecological methods–to build a base of consistent individual customers.

“In Puerto Rico, where agriculture has been forgotten for two or three decades, agroecology is a fight for the freedom that we don’t have in many senses as a country-slash-colony,” she says. Agroecology prioritizes working with the local ecology and serving smaller communities. Historically, Puerto Rican farms have used inorganic pesticides and monocrop systems, focusing on cash crops–coffee, sugar, and tobacco. These don’t feed a population. “If we import 85 percent of our food, then we have 85 percent of an opportunity to grow our own,” says Díaz. “Why would we do it in a way that has been proven not to work?”

The question for the future, then, is how to provide more access to fresh, locally grown produce for the 43 percent of island citizens who receive food stamps from the government. That program’s funding has been cut, down from $649 to $410 per month for a family of four, and the credits are restricted to certified stores only–whereas in some locations in the States, you can use food stamps at farmers’ markets. On the island, a percentage of Nutrition Assistance Program funds can currently be withdrawn as cash for use as the recipient wishes, but that will be fully phased out by 2021.

For an agroecology movement just getting back on its feet after a cataclysmic natural disaster, though, the progress has been staggering. As structures are rebuilt, food producers and activists are mapping out routes to feed every Puerto Rican. The hub created by PRoduce has the potential to engender the same sort of understanding among those who can afford it that Huerto Semilla and the Service Brigade are building with hands-on work, and that Frutos del Guacabo explores through its disciplined, scientifically minded approach.

As Díaz says, when just 15 percent of the small island’s produce is raised locally, there’s a huge amount of space for new approaches to emerge and grow. Even on a small island, there are microclimates–opportunities to plant seeds in many different soils.

Read the next installment: “The Future of Food, As Seen From Puerto Rico”

Read the previous installment: “Growing Food To Rebuild Puerto Rico”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. Isla del Encanto is a four-part series in both English and Spanish about the future of food in Puerto Rico. From gardens to labs, bakers to distillers, Puerto Ricans are seeking agricultural sustainability and sovereignty.