What do you fear about the changing climate? What do you worry will happen to the places you live?

The specter of climate change is often communicated through a range of what are now visual clichés–mayhem and disease due to overpopulation, Mad Max-style water shortages, marooned and starving polar bears, and myriad other issues that will bring us all death, war, and unbearable heat.

One problem that doesn’t always make it onto that list of clichés, though– maybe because it’s already associated with hot, dry places–is the forest fire. For coastal cities, rising sea levels are the most direct threat from a changing climate. New research has revealed, however, that for many of Europe’s largest cities, forest fires will become a regular menace–and far sooner than the threat of flooding. They could even lead to some of the continent’s most important metropolises becoming uninhabitable within the next century.

To understand why, though, we’ve got to look at how those cities have grown over the last half century.

The pattern of urbanization around the world in recent decades has led to urban and rural areas encroaching on each other, as farmers have been pushed off their land, leaving it empty for both city sprawl and overgrowth. The firefighting community has a name for this kind of in-between space: Wildland Urban Interfaces, or WUIs, defined as “the area where structures and other human development meet or mix with undeveloped wildland.”

Unless your city has been exceedingly smart about planning, WUIs probably molder in urban outskirts near you. WUIs exist for a number of reasons, including dramatic changes in land use, increased urbanization, and the development of low-density residential areas (like suburbs where people need cars to get around), leaving plenty of dry plant life around for fuel. Economic and agricultural policies can also be partly responsible–for example, through the subsidy of crops like olives, which the EU spends €2.25 billion [$2.54 billion] on each year.

Afforestation–when new forests are established in areas where they weren’t before–has been another trend in Europe, one that’s well intentioned but problematic. Often, the rural communities that made sure of the health of forest boundaries through things like controlled burns, no longer exist. City dwellers are rarely equipped with the know-how or accountability needed to reduce fire risk in their nearest wild ecosystem. (Have you ever heard of a suburban family going out on a weekend to clear dead kindling from the woods?)

Everything combines to turn forests into fuel, making fires bigger and more difficult to extinguish–and that deeply threatens the cities that have these edge spaces. And for the first time, we have an idea of exactly the scale of the problem.

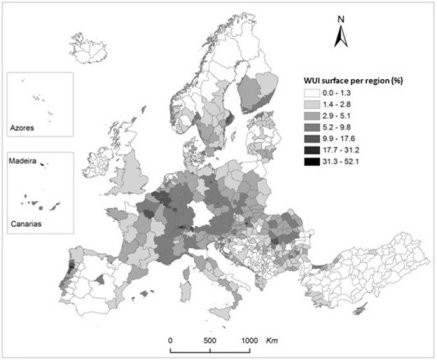

A team led by researcher Sirio Modugno at the University of Leicester has produced a Europe-wide map detailing the areas most at risk for devastating fires–and many of them border major cities you wouldn’t expect to be at risk.

Using satellite images and land cover data, the team found that the frequency of large fires is linked to how close an area is to the nearest WUI. The new map reveals that these areas are common throughout Europe, surrounding many large cities and, in one case, forming a corridor between Prague, Dresden, and Berlin. The team’s analysis found that popular tourist destinations like Sardinia, Madrid, Valencia, and Catalunya are some of the cities and regions most likely to have large areas nearby at risk of catching fire. Their hot summers, and the added pressure of climate change, make the threat of fire even more pressing.

For one example of how local governments can exacerbate a natural threat, look to Spain. The Communidad de Madrid (CM), which includes the city of Madrid and surrounding municipalities, is at risk because of its own hasty growth over the past several decades. According to Richard Hewitt of the University of Alcala, growth in the CM has accelerated in all the categories that also grow WUIs. There were new forests planted, but the same amount of land was covered with human surfaces, like airports, roads, railways, sports facilities, and industrial sites.

There are lots of reasons–regional, national, and global–for why so much sprawl appeared around Madrid. The city has been physically expanding since the 1980s at a pace that far outstrips its population growth, with attitudes in local government that saw building anything and everything as an economic good in itself. These attitudes were formalized in the 1998 Natural Land Act, which allowed all unprotected land to be urbanized. In practice, much more land was wasted in the development of detached suburban homes than was needed to support the areas’ residents. According to Madrid resident and urban planner Marco Adelfio, these developments reflect the “Americanization” of city design in Spain at the time–complete with corporate campuses, “big box shopping [centers and] underused parking lots.”

During 2007, the last year of the decade-long Spanish property boom, more new homes were constructed in Spain than in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom altogether. Construction was incredibly important to the Spanish economy, contributing a significant portion of the nation’s GDP, and providing a reliable pipeline of jobs for young people. The boom ended abruptly and painfully with the puncture of the global real estate bubble, and led to an unprecedented recession in Spain as in elsewhere around the world. The country’s residential tourism attractiveness drew global speculators in legion, as Spain was being called the “tip of the global housing bubble.” This is most often cited during discussion of the current, agonizing mortgage crisis in Spain–where tens of thousands of families face foreclosure on the homes they bought during the boom. It also undoubtedly had a negative impact on sustainable urban growth, with massive, sprawling, empty suburbs strewn across the dry outskirts of cities. Academics (like, for example, Jesus M. Gonzalez Perez from the University of the Balearic Islands) have argued that the environmental damage inflicted during this time is likely irreversible.

Recovery efforts by the national Spanish government may have worsened the crisis by providing an artificial boost in construction jobs. The 2008 stimulus plan gave support to construction firms affected in the collapse, and according to Perez earned the ire of environmental organizations for its disregard for sustainability. The continued construction was marked by non-intervention on the part of the regional government to ensure sustainable development–Veronica Hernandez-Jimenez of the Polytechnic University of Madrid suggests that this was in part due to the financial interests of some political insiders. Jimenez states that before the crisis, when voters generally lacked awareness of sustainability issues, politicians successfully–and duplicitously–argued that the economy could be harmed by greater regulation of development. While international observers and environmental groups were well aware of the damaging practices in place, it appears that there was little grassroots energy addressing the problem.

Madrid is a unique case, but it demonstrates the importance of discussing climate change-related strategies at the local level, and focusing on prevention of disasters easily foreseeable because of tools like the WUI map. While there have been recent legislative efforts in affected countries to mitigate fire risk, Modugno said the laws are not yet old enough for us to make any real conclusions.

How can we save our cities, then? One possible solution already employed in many cities around the world is multi-functional agriculture, where urban land is used for growing crops in addition to serving as a buffer between areas with conflicting land use. It’s already being trialed in cities like Beijing, Accra, Pretoria, Kathmandu, and Dakar–developing world cities where urbanization has already had to take place alongside constant threats like fires and desertification, and lessons have been learned the hard way.

What’s increasingly clear, though, is that forest fires are another thing we should add to the climate change cliché playbook, alongside polar bears perched on icebergs and CGI renders of Big Ben, or the Empire State Building poking up from beneath the waves. And unlike rising sea levels, we’ll likely see the impact of forest fires much sooner. When the stakes include the fate of beloved cultural landmarks, tourist destinations, and environmental wonders, though, it might just make preventative action a little more likely.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Metropolis section, on the way cities influence new ideas–and how new ideas change city life. Click the logo to read more.