I think there is something wrong with us. I think we have a problem with power, and with our fantasies about power. Just a few weeks ago, I would have said I was an evangelist, a person who believed in the power of technology and entertainment to teach us things, and to be good for us. Now it’s as though a cord has been yanked from my back. I’ve been decommissioned, it feels like. I would like to write something optimistic, I really would, but those words won’t come.

Even before the election, the “criticism” element of my work in technology writing was difficult. If you don’t look toward the future with the dreamlike optimism of a new day, you might be a Luddite. You can be skeptical of products only inasmuch as your skepticism serves the consumer–beyond that, you’re ruining the fun.

It’s a possibility space, people say. You might not like, say, virtual reality right now, but you’re going to like it. It’s not there yet, but it’s going to be. Do not, for any reason, try to tap the brakes. The future is coming and there is nothing you can do but open your arms.

But to whom have we been promising possibility? Whose future is coming, and with what will they be armed?

You can see what I’m talking about in HBO’s latest show, Westworld–a piece of speculative fiction about human fantasies and the ethics of enabling them. In the show (which revisits the 1973 film of the same name), rich guests pay to play their days away in a gigantic Wild West theme park populated by stunningly realistic robot actors who exist to fill their wildest dreams. Much as in lots of popular open world videogames, you can be a hero, a villain, or neither; you can select which characters to follow or which quests to accept. In this highly realistic, designed world of pretend, you can hang out in the bustling Western town center–or ride off to confront your fears and find out “who you really are.”

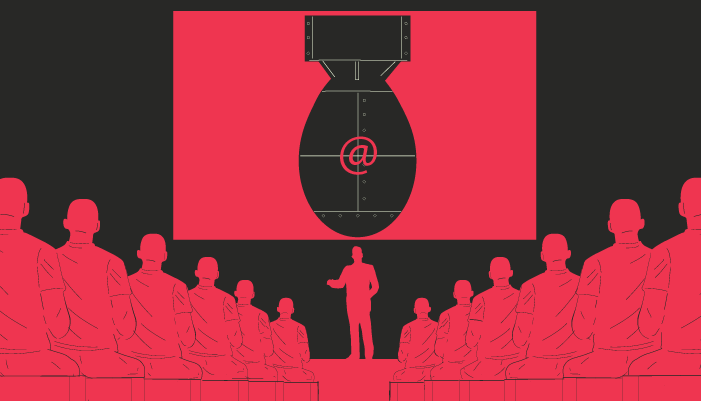

This vast and impressive infrastructure is designed to cater explicitly to the power fantasies of its visitors, whatever those may be. Today’s videogame industry has long promised an endless march of realism and immersion, and the experience suggested by the TV show imagines the plausible evolution of those values. The designers’ appetites and intentions–including the ethical ramifications of subjecting artificial intelligence to human appetites–are subsumed by the main goal, which is that the player must be able to achieve any of his desires. All of them. Even when it frustrates the designer’s craft or intention, letting the player tell his own story is thought to be the ultimate in experience design.

In a moment that reminds me of so many videogame presentations I’ve endured, the smarmy Head of Narrative in Westworld presents his newest storyline: an array of scantily clad, artificial women’s bodies and native warrior stereotypes, guaranteeing players more “visceral” experiences than ever before. His implicit promise: Even more sexism, even more racism, even more violence–that’s the way to give the people what they want!

It’s painful to watch, and I’ve seen it in the real world dozens of times. Transplant a guy from an indoor hobby onto a big stage and make him perform for an audience that simultaneously includes 18″”24-year-old boys alongside graying investors–about a product that cost millions and millions to make–and the result is awkwardness, discomfort, blatant sexism, or too many people over the age of 40 insisting on saying the word “badass” multiple times. The only thing Westworld got wrong was making that guy a little too charming.

Whenever I used to write about videogames–something I’ve since quit doing–I always felt acutely that I was up against a major contradiction. While everyone can understand play as a healthy, expressive, or even educational thing that all humans do, the gun-toting norms of the popular industry mean that people can’t always see videogames as part of that concept.

Until recently, my view was that the work of designing and playing modern games didn’t need to be enslaved to the commercial game industry. The bulk of the industry wears an albatross comprised of unsustainable economics, heartbreaking working practices, arcane vocabularies, expensive hardware, obsession with violence, and tacky aesthetics. You should, I thought, be able to enjoy the intersection of technology and play in all kinds of creative and social spaces without necessarily being herded into dank convention centers full of adult men queueing for posters and stuffed toys. That, I thought, was the industry’s insular past–not its inspiring, mainstream future.

I thought that cheaper tools, a broader range of creator communities, more cultural diversity within the traditional “male power fantasy” environment, and a shift in priorities toward touchable, expressive, and humane types of works would be a net gain for an industry widely misunderstood. Most of all I dared, regularly, to suggest that better treatment of women, both as characters as well as employees and audience members, was one key way toward a more sophisticated and diverse future for the medium.

Despite that reasonable belief, the industry model whereby wealthy white men peddle power fantasies that throttle everyone else’s needs out of consideration remains alive and well. In fact, we can probably expect it to grow, as interest in interactive entertainment bleeds out of the traditional “gaming” space and into other areas of technology such as virtual reality, augmented reality, and artificial intelligence.

Virtual reality seems to physically affect men and women differently, but few people seem to care. Some even disbelieve it in the face of personal reports. Women, their bodies, and their sense of personal space have enjoyed unequal treatment in virtual worlds since long before the Oculus Rift and its contemporaries–Nick Yee’s “The Proteus Paradox” explores how virtual spaces actually calcify our biases, not challenge them, while Julian Dibbell wrote the seminal “A Rape in Cyberspace” all the way back in 1993, and that’s just off the top of my head.

These problems spill out into the rest of the world as technology becomes an ever-larger part of more lives. Too many firms relentlessly pursue the next big thing and are not at all interested in learning from the countless reports of women having a bad time on existing platforms, or in testing out the tools or features we ask for.

Twitter shows stubborn disinterest in disabling harassment infrastructures on its platform–as if the rewards of spending development time on equality or safety don’t match the rewards of spending resources on advertisers and power users. Microsoft somehow managed to release a teen girl AI onto Twitter without foreseeing that she’d be turned, nearly overnight, into an abusive racist as she learned from those she spoke to. Again and again we see tech companies with millions of users and years of development time–sometimes even decades–release thoughtless “innovations” that could only be born from a blatant indifference or disregard for our needs.

And so far we’ve only talked about women–not about people of color, or poor people, or otherwise marginalized folks who will also face obstacles to participating in our glorious new future of tech-enabled make-believe. While San Francisco faces emergency levels of homelessness and a public health crisis, the boys of Silicon Valley swim ever deeper into their pricey playlands. Young Oculus CEO Palmer Luckey even suggested that one solution to the hardships of living in poverty would be to escape into one of his $600 headsets.

Luckey isn’t necessarily wrong to suggest that virtual reality and entertainment technology might be able to offer us experiences we might not otherwise have access to. But why is the industry only concerned with what those who already have so few limits would do if they had none? The oppressive, power-crazed politics of the right, and the sexist, privileged world of entertainment technology go hand in hand–and are holding on ever tighter to each other.

When I was harassed in an attempt to get me to abandon these positions during the embarrassment that was “GamerGate,” everyone told me it was just a radar blip. They said that the hit pieces on Breitbart about me, other women, and progressive voices in technology were just fringe issues. We should not give them any more attention, everyone said. They couldn’t have been more wrong.

Now the CEO of Breitbart, Steve Bannon, is an advisor to incoming president Trump. And in the last few weeks all those same old people, the dross of imageboard culture with their same assembly-line right-wing memes, are back in my Twitter timeline letting me know they “won.” To pretend there has never been any connection between the tech consumers of two years ago, raging on the internet about too many women and people of color in their expensive toylands, and the great upheaval we face in America right now would just be delusional. These people’s fears, their power fantasies, are now steering the world.

Perhaps we can’t change the consumers. But we can–and we must–offer different definitions of power, different fantasies for different people. If we’re creating our dream worlds in these designs and devices, there must be room for the idea that not all of us have the same kinds of dreams. What else might human beings want besides great power, freedom from consequences, and uninterrupted time with fictional women? Those are fine dreams for some, of course, but what about the others–for people whose far-off ideals simply include safety, acceptance, respect?

Creators take note: We don’t need to make yet more realms where the power fantasies of these male consumers are everything. We need more means for the rest of us to escape the one they’ve already made for us.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our The Power of Play section, which looks at how fun and leisure can change the world. Click the logo to read more.