There are lots of ways you could contribute to combating Ebola. One is by helping to build better maps for those working on the ground.

“It’s difficult to plan if you don’t know where things are,” said Kate Chapman, executive director at the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT). “You can’t send out health workers to do a survey; you can’t necessarily accurately plan travel times.” She continued, “In a lot of places there isn’t accurate base map data–roads, critical infrastructure information, even place names, where villages are, stuff like that. There are a lot of issues if you can’t look at things from a geographic perspective.”

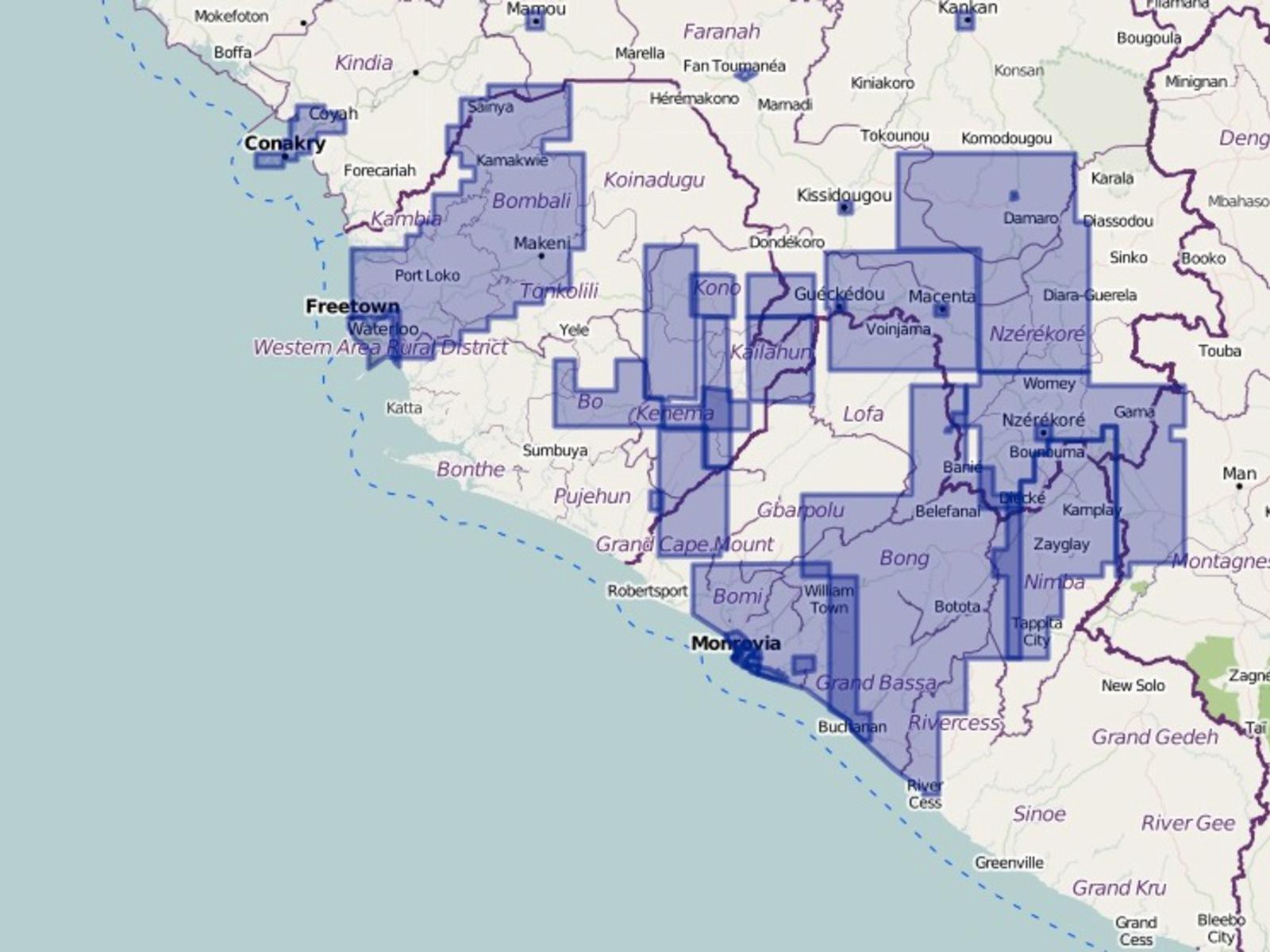

HOT’s aim is to improve that geographical perspective, applying satellite data and a global network of volunteer mappers to fill in the gaps. The process is relatively simple. The OpenStreetMap task manager divides an area into squares. Someone claims a square to map. Volunteers use satellite information to trace-over identifying features. “For example, if they see a road in the picture–you can imagine just following that along with your mouse and clicking along that road–they outline where it is,” Chapman explained.

This builds on previous work the team executed in response to Typhoon Haiyan last year and the Haiti earthquake in 2010. Over 2014, Chapman and company have also been mapping data in the Central African Republic. HOT will go anywhere maps might help.

Volunteers vary. “There are people who give more than a full working-week worth of volunteering,” Chapman told me. “People who are very active. But there are people who just know OpenStreetMap and have a spare hour or so.”

As SciDevNet journalist Aamna Mohdin noted earlier this month, there are ethical questions associated with these sorts of mapping projects. Does mapping vulnerable communities for the first time put such groups in danger?

Some also wonder about the accuracy of work produced by amateur mappers, rather than professional cartographers. Might they slip up, input the wrong information, and be doing more harm than good? Chapman argues that the volunteers’ accuracy is generally pretty good, comparable to traditional data sources at least. Moreover, as reported by Nature this week, the citizen cartographers of OpenStreetMap are working with citizen scientists of the Zooniverse to figure out how to best improve their system.

“It’s sometimes hard to trace a map to a specific decision that was made,” Chapman added, but confirms she’s heard from workers inside the Red Cross and Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) that their maps are being used. HOT first launched work to map Ebola-affected areas in March after an urgent request from MSF for help supporting its relief efforts for an Ebola-like outbreak in three towns in Guinea. They then reactivated efforts in July, following the second wave of the outbreak, after a call from Red Cross and MSF workers currently deployed in Sierra Leone.

Chapman’s keen to stress that anyone can get involved. “Anyone who knows how to use a computer, who is interested in learning, can help,” she said. “It’s a great way for people to get involved [in work combating Ebola]. Maybe they’ve already donated money, and they are looking for something else to do, or they can’t afford to. It’s something all sorts of people get involved in. You don’t have to be a super-mapper already. It’s something you can learn to do.”

If you want to volunteer, there’s full information on the HOT site.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Vital Signs section, on the future of human health. Click the logo to read more.