Children don’t wear shoes to school in the Ugandan village of Kitengesa. In this equatorial farming town, they show up barefoot. And sometimes the girls don’t show up at all.

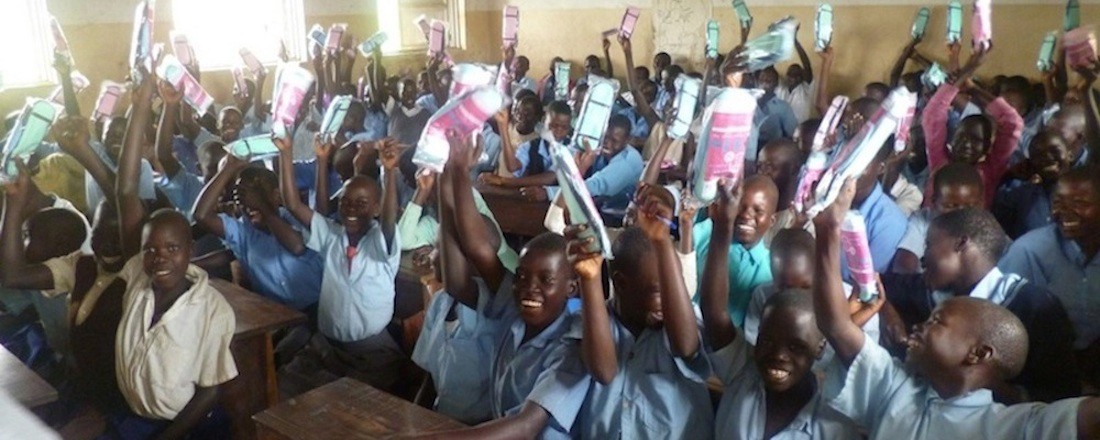

In a trend not unique to here, they skip a week of school every month with different excuses each time. The thing is, these girls are not sick–they’re joyful children who want to be out among friends. But they’re menstruating. So they stay home to avoid the shame and fear they feel when they leak through the old rags, leaves, newspaper scraps, pieces of foam mattresses, and banana fibers they use to manage their periods.

For the most part, there isn’t running water, or sanitation facilities, in Kitengesa. Girls and women can’t wash up as they bleed. There’s no place private enough to dispose of their used materials. They suffer from profound self-consciousness–not to mention recurrent infections–during what is culturally known as their “week of shame.” This amounts to, in many places, a flat out violation of the right to human health.

“Before receiving AFRIpads, I was using a piece of cloth when I was in my period … sometimes in the afternoon it started to smell. And when I was in school I couldn’t change so I had to keep it there all day.”

It wasn’t until volunteering at a school in southwestern Uganda with her husband, Paul, that American Sophia Grinvalds experienced the vacancy of menstrual support firsthand and recognized exactly why girls were skipping class and women were missing work. When Sophia got her period one month and was out of pads, she sent Paul to the nearest village for supplies. He came back empty-handed; there weren’t any pads available at the shops in town.

The widespread statistics related to this issue were grim, the Grinvalds found. The sheer unavailability of feminine sanitary products and proper sanitation in developing countries contributes to an average of four to five intentional school-day absences each month among female school children. With a fifth of the educational year missed, girls fall behind and drop out of school altogether, significantly increasing teen pregnancy and early marriage rates, and sabotaging career opportunities.

And it’s not just happening in Uganda. Girls and women are enduring a common experience in villages and global cities alike.

- In urban India, while a disparate 43″”88 percent of girls use reusable cloths, they wash them without soap or clean water.

- In Burkina Faso in West Africa, 83 percent of girls have literally no place at school to change their sanitary pads.

- In Nairobi, commercial pads are too expensive for low-income girls to afford so many, aged 10″”19, reported having sex with older men to pay for their menstrual needs.

- In one study by HERProject, 73 percent of the Bangladeshi garment workers interviewed missed work for an average of six days per month, going unpaid, due to vaginal infections.

In 2010, the Grinvalds founded AFRIpads, a socially responsible business headquartered in the Ugandan capital of Kampala that locally manufactures cost-effective, reusable sanitary pads. The concept is modeled after Canadian company Lunapads, which makes washable pads for eco-conscious women in North America. The key to success in a place with so few resources is reusability (one AFRIPads kit lasts for 12+ months), a concept very much part of the discussion when the Grinvalds contacted Lunapads to see if they could model the product for an African market.

While AFRIpads has maintained a partnership with Lunapads, as well as companies like THINX in New York, Moxie in Australia, and the non-profit AFRIpads Foundation in the Netherlands–which mostly follow the buy-one, give-one model borne out by the likes of Warby Parker and Toms–manufacturing is intentionally kept local. The bulk of company sales and distribution happens outside the country, however, said Helen Walker, AFRIpads’ Communications & Partnerships Officer. Walker was the first employee based in Kampala in 2011 and sent around Uganda to spread the word as company salesperson.

The Grinvalds looked at first to construct an all-Ugandan product, but the necessarily absorbent, fast-drying, and stainless textiles simply weren’t available in the country. Using imports from China and Kenya, the 90-percent female AFRIpads staff produces 3,000 Deluxe Menstrual Kits each day. As of March, this all-in-one design with wings is three times more absorbent than the original, dries in two hours and lasts 12+ months, and is manufactured with heavy flow in mind. Cleaning for reuse requires soap and water (well water works where running water isn’t available). While the 10 textile-cutters are men, the other 120 tailors, quality-checkers, supervisors, and packing department employees based in Masaka, near Kitengesa, are female.

To date, AFRIpads has managed to distribute 750,000 kits worldwide with the goal of reaching one million women by the summer of 2016. Despite ambitions to reach women in small villages in developing countries, most of its customers are big NGOs and international relief agencies that funnel the product to refugee camps. As it turns out, the reusable pads are a very practical solution to rapidly overfilled latrines in camps all over the world. And perhaps even more crucial, they address a distribution problem that organizations confront when looking to supply girls and women with disposable pads each month–AFRIpads get delivered once a year.

To be clear, though, said Walker, “We do sell our product! That’s actually key. We don’t want to be a give-away product. We want to be an aspirational product that girls and women actually want to spend their money on–not a free handout they get without maybe even needing it.”

As such, the team recently launched a retail brand, “So Sure,” that it hopes will become available all over Uganda. “We want to make sure that girls and women can actually access our product themselves,” said Walker. Currently, the one-year, deluxe menstrual kit costs UGX 13,000, or USD $4.65. So Sure kits, sold in two packs, are half that price.

And while physical distribution is one goal, AFRIpads works under an operating ethos that believes menstruation should not be a barrier for any woman, anywhere. Its team wants to change the negative attitudes and perceptions around menstruation. “Women are the backbone of our societies and they deserve access to safe and dignified solutions to managing their periods,” say the founders. That’s why AFRIpads took the helm of coordinating all activities in Uganda this May on the second annual Menstrual Hygiene Day (MHM). Some 290 coalition partners over 30 countries added voice to the harmful void of silence around awareness for the importance of good menstrual hygiene. For its part, AFRIpads joined with all other MHM partners in Uganda to organize an advocacy walk up to Parliament with 1,000 participants–many of them school-age boys and girls.

The quiet placement of a new product on shelves just isn’t enough to fight centuries of cultural taboo in places like Africa, India, and South Asia. “Menstruating women and girls are wrongly considered to be “‘contaminated, dirty, and impure,” said Walker.In addition to inaccessibility, women also fall victim to inadequate pubescent education. “Often girls don’t even know what is happening to them when they get their period for the first time,” said Walker.

“It’s not a topic you can openly discuss with your mother. They think something is wrong with them if they see blood.”

–Helen Walker

She continued, “And there are many stories going around. Many girls think that having sex can take away the pain associated with menstruation for instance, and many women believe that the chemicals in disposable pads will make you infertile.”

After outrageous growth over 2014, production is afoot on an expanded facility in Kitengesa village–the place where AFRIpads began. The company has purchased a big spot of land with the intention of combining the existing four product locations into one central production hub with day care for employees’ children and a garden where the women can grow their own fruits and vegetables. “We always joke and say that we employ the whole village, but that’s basically the case,” said Walker.

Employment is no doubt vital. Of course, what’s left, is to get them all talking.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Vital Signs section, on the future of human health. Click the logo to read more.