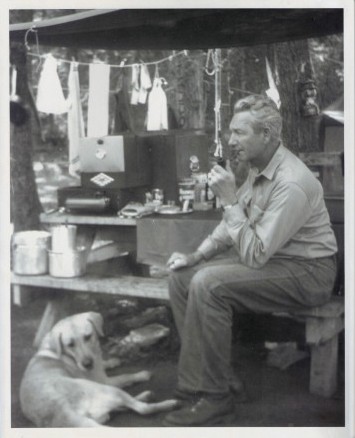

I was not alive when my grandfather, a proud Minnesotan pilot of a B-17 bomber, returned from Germany as a tired prisoner of war. But I am told that he wouldn’t eat potatoes. He also refused to talk about his experiences in the Stalag Luft III camp and the crew members he lost when the Germans shot down his plane as it passed over a small town in the Netherlands. He died long before I had the courage or maturity to understand the complexity of confinement or loss.

Growing up, I had the distinct impression that there were two types of people in the world: the people who fought wars and the people who were protected by them. It took me many years to understand that conflict touches an entire population of individuals–family back home, journalists, human rights activists, prosecutors, researchers, archivists, historians, and so many others. Wars take a toll not only on the soldiers who fight them, but also on the people who work to make sense of them.

In June 2016, I found myself at the bottom of the Harvard Law Library in a windowless room with Dr. Matt Seccombe, a historian and document analyst with the Nuremberg Trials Project. He’s spent over six years, between 1998 and 2016, combing through more than 50,000 pages of trial documents about the military and political leaders of Nazi Germany for the Harvard Law School Library–which is now making them available digitally in a publicly searchable database. Seccombe has also written extensively about his findings in a series of online posts, titled “Scanning Nuremberg,” on the Harvard Law School Library Blog Et Seq.

When I met him, I was on the verge of wrapping up my M.A. thesis on the people and policies who had shaped the collection of resources at the Guantánamo Bay Detainee Library. We were there to discuss wartime, war crimes, war tribunals, and, in particular, how to look at related transcripts, pictures, and videos in a professional capacity for hours on end without imploding.

I kept asking Seccombe how he handled the psychological taxation of performing document analysis on so many pages of trial evidence about Nazi experiments in human freezing, oxygen deprivation (high-altitude), poison gas, and chemical sterilization. How did he endure the onslaught of details about the removal of bones for anatomical research, Jewish skeleton collections, forced sterilization programs, and the mass murder of civilians? I needed to know what he did to relax at the end of the day. “I try to leave the work behind,” he said, “but sometimes I still get nightmares.”

Nearly a year later, I still write to Seccombe almost weekly. When we really need a break, we tend to discuss our latest “canine-friendly moments.” Neither of us owns dogs. We just like to talk about them.

I often think about how people who investigated crimes against humanity did their jobs before the digital age. I think of those who hunted down war criminals like Adolf Eichmann, Nazi mastermind and chief of the Jewish Office of the Gestapo, without the help of encrypted apps and geolocation tracking tools. After destroying all the negatives of the photo on his official Gestapo identity card, Eichmann evaded capture for over 15 years until Israel’s Mossad intelligence service tracked him down in Argentina.

These days, offenders are easier to trace since they’re more apt to leave digital footprints behind. There is so much more metadata to collect and sort. In some cases, unlike war criminals from Nazi Germany, malefactors from terror organizations to everyday folks use the internet as a stage to showcase a range of hate speech, sex crimes, and brutal murders. Many affiliates with the Islamic State are even choosing to show their faces or speak on camera. After Mohammed Emwazi, also known by his nom de guerre Jihadi John, appeared in multiple videos released by the Islamic State, his mother is said to have immediately recognized his voice. Journalists rushed to compare different audio files, trying to verify if Mohammed Emwazi was indeed the same man responsible for beheading numerous journalists in ISIS-controlled territory. These days, though, you don’t necessarily have to belong to the media or an intelligence agency to hunt for criminals and analyze the damage they’ve done.

But where do you start if you’re trying to trace someone’s digital path–with an unverified Facebook page? And perhaps more crucially, where do you stop, when one Twitter feed leads to another, which leads to another? In my case, new technologies and the immediacy they offer mean that individuals without decades of training in war crimes research can now actively contribute to the future of an ever-morphing field. But with this and other kinds of similar work come the potential for technological oversaturation and mental distress, meaning people in the field need new ways to cope. No matter your specific job or angle of approach, the whole process can become a bit of an emotional rabbit hole.

In February of 2015, I did a Google search for Noam Chomsky, and by some fluke I landed on an old Foreign Policy article titled “Noam Chomsky Books Banned at Gitmo.” The very idea that there was a library for detainees at the Guantánamo Bay detention camp excited me, and left me with questions that were not Googleable. How did the Joint Task Force of Guantánamo determine which books were permitted or prohibited in the library? If the detention camp closed, what would happen to its extensive collection of books, magazines, and DVDs? Did the Department of Defense (DoD) add different language groups to the collection as the detainee population expanded? How did the Detainee Library at GiTMO compare to, say, the offerings in the United Nations Detention Unit (UNDU) in The Hague or the now-defunct Parwan Detainee Library in Afghanistan?

I emailed American journalists like Charlie Savage, who started covering the GiTMO beat before I was 10 years old. They advised me to talk with habeas corpus attorneys who might know more about the library’s history and development from conversations with their clients. So I started to conduct interviews with the lawyers; it was one of the only ways I could learn about the language proficiencies, literacy levels, and reading interests of detainees.

Somehow I grew to like the labyrinthine quality of the work. I dug into reports with broken hyperlinks, figured out how to use web archiving tools to uncover lost photos from GiTMO, and gradually became comfortable with emailing and phoning the Department of Defense. I once made a media spokesperson at the DoD laugh, because I was unversed in the NATO phonetic alphabet and spelled my name on the phone as such: “”‘M’ as magical, “‘U’ as in unicorn, “‘I’ as in iguana, “‘R’ as in Rwanda, “‘A’ as in Anglophone.”

Since I couldn’t directly ask prisoners at GiTMO what they thought of the collection of books in the library, I expanded my research to detainees imprisoned and awaiting trial elsewhere. I sent a list of questions to Radovan Karadžić, a Bosnian Serb poet, psychologist, and, as of May 2016, a convicted war criminal found guilty of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity during the Bosnian war (he is currently appealing his conviction in The Hague). I asked him about what he’s been reading during his detention (answer: Whitman, W.H. Auden, and Emily Dickinson).

I’m still a rookie. I don’t always know how to take a break from constant engagement; when to stop searching the Harvard Law database, emailing DoD media spokespeople, scheduling Skype dates with attorneys, or skimming PDF after PDF of GiTMO standard operating procedures. Since this type of work has changed over the decades, I wanted to get a sense of how more experienced reporters and researchers handle its new landscape.

I first reached out to an investigative reporter who has spent the past few years messaging people trapped in ISIS-controlled towns and scanning ISIS forums online. I wondered what strategies she used to keep sane, to stay in the light while researching undeniable darkness. In her response to me, she admitted that she runs, and binge-watches Modern Family. I had hoped for something more strategic, so I kept digging.

When I began to poll others in the field about their de-stressing activities, I assumed they would mostly talk about tossing their tech into the nearest body of water. But Alexa Koenig, executive director of the Human Rights Center at Berkeley Law School, confessed to me that in the beginning stages of her war crimes research she too escaped screens by looking at other ones. “I was also a big fan of what I came to call my “‘brain candy’–watching comedies that took little brain power to process and ended on a positive note,” she said.

Recently, Koenig brought in Sam Dubberley of Amnesty International and Eyewitness Media Lab to speak to her students at the Berkeley Human Rights Investigations Lab about coping mechanisms. Much of the students’ daily training involves learning to use open-source intelligence, or data publicly available in places like Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube, to confirm violations of international humanitarian law. In practice, this often consists of verifying and authenticating hundreds of hours of video footage and photographs of human rights abuses submitted by investigators, survivors, and human rights activists in places like Syria and Yemen.

Koenig wrote up some of the takeaways from Dubberley’s visit and compiled them into a chart she’s hung up in the lab titled “Resiliency Reminders.” When I dropped by for a visit, many of the suggestions seemed almost too simple and silly to be effective (e.g., “Work on breathing exercise,” “Treat yourself to antidotes to violence–pictures of cute animals, sitcoms, babies”). Then there was this list of work-oriented “Tips and Tricks”:

- Adjust settings in Facebook and Twitter to turn off autoplay

- Use Post-its to block out graphic material when viewing video repeatedly

- Turn off the sound

- Adjust window size of the video to small

At the bottom of the sheet, the last sentence in bold red caps reads: “WE ARE ALL HERE TO SUPPORT EACH OTHER.” If I’ve learned anything in the past two years, it’s that it takes a village to do this kind of work–so it’s a real privilege to have access to a community of individuals sharing the same longitude and latitude, and the same box of Kleenex.

Like her students, Koenig herself is also in deep. “I’ve been supervising the verification of videos provided by the Syrian Archive. I was also involved in monitoring the recent elections in the Democratic Republic of Congo, although there was a period when it was hard to get information out from the ground,” she wrote to me. “I’ve also been consulting on our two legal cases–one of which concerns a situation in Central America and the other in an African country.”

Joanne Mariner, a senior crisis response adviser at Amnesty International who has investigated violations of international human rights and humanitarian law in Sudan, Afghanistan, Ukraine, Colombia, the Central African Republic, and the Balkans, said that for her there’s rarely a turn-off button when it comes to war. “I wake up in the morning, and the first thing I do is grab my phone and see what horrors have occurred while I was asleep.”

But she also pointed out that just as technology brings an omnipresence nearly impossible to escape, sometimes it can provide relief and reassurance when other aspects of conflict become unwieldy and unpredictable. She spoke particularly of the comforts that encryption apps like Signal and WhatsApp provide: “One of our biggest concerns is the threats to local human rights activists and others we communicate with, and the possibility of government surveillance. The use of encrypted messages apps helps assuage some of these concerns.”

Paul Deschner, a developer and project manager at the Harvard Law Nuremberg Trials Project who has coded and created much of the database, also takes comfort in advancing the work itself. “Creating a virtual room folks can walk into to find and examine documents underlying the culture of the Nazi regime seems really worthwhile,” he said. “And recent political events put that into even greater relief. My main sense of satisfaction relating to the project comes in making evidence of these documents. Bringing them to light. Making them accessible.”

About a year ago, I began to see traces of GiTMO everywhere. When I walked into a bar to find the World Cup on TV, I thought immediately of the time then-presidential candidate Donald Trump lambasted the Department of Defense for building a million-dollar soccer field at GiTMO during a campaign speech. When I drove by a zoo, I thought about the Cuban rock iguana population, which received protection under the U.S. Endangered Species Act after researchers studied aboard the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station. When I watched the Oscars and spotted Dakota Johnson on the screen, my mind wandered to GiTMO’s Fifty Shades of Grey controversy. I was slowly documenting the history of the detention camp in U.S. pop culture with an archive in my mind. It wasn’t healthy.

In May 2016, I hit a breaking point: that is, I went through a breakup. I lost someone who had so very much wanted to hear about my work and read my writings–but I had refused because the words simply weren’t ready, because I had so many emails to send, because I had so many legal documents to read, because my questions always led to more questions. I had no time for fiction podcasts. I had no time for board games about quilting. I had no time to go for a run. I had completely lost myself.

Since then I often return to an email exchange with Nikolaus Wachsmann, a professor who spent over 10 years researching and writing KL: A History of Nazi Concentration Camps. In an email to me last July, he wrote, “Perhaps the most important piece of advice I can give you is to keep trying, throughout your research, to strike the right balance between scholarly detachment and empathy–which is easier said than done.”

Now, I talk about my work (the part that’s on the record) with friends who don’t spend their days thinking about confinement or conflict. It helps me feel less alone. I even learned a few breathing exercises from a New York yogi, and while I think they’re silly, I do do them.

I also think more about the bureaucrats, government officials, and active-duty servicemembers on the receiving end of my emails. They undoubtedly have stressful lives, too. I’ve learned that when trying to decipher the nuances of conflict and technology, it is rarely healthy to remain on a warpath.

In a recent exchange with Matt Seccombe, I asked if he had any advice for future war crimes researchers. He returned to a common theme in our correspondence. “Get a dog,” he wrote, before adding: “They have to accept that if they take this seriously there will be some difficult days and maybe some nightmares. They should expect this to come and to pass. They may get some emotional/mental bruises, but they won’t break.”

He went on: “Remember that even the shocking material is interesting, often fascinating at the level of fine detail, so it’s always a learning experience (to use the cliché). It helps to ventilate some of the pressure, either by writing about it (e.g., my monthly reports) or talking about it. It’s important not to get completely absorbed in it–hence the dog.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our The Way We Work section, which looks at new developments in employment and labor. Supported by Pearson. Click the logo to read more.