The piano is a very refined piece of technology. Dr. Andrew McPherson, senior lecturer in digital media at Queen Mary University of London, respects that its hundreds of years of development is architecturally remarkable.

But very little has changed in the past century or so. Innovation around the piano seems to have stalled. While still maintaining the current culture of piano-playing and what makes the instrument so great, can we change that? Maybe McPherson will be the one to do it–with the electronically-augmented magnetic resonator piano he’s built.

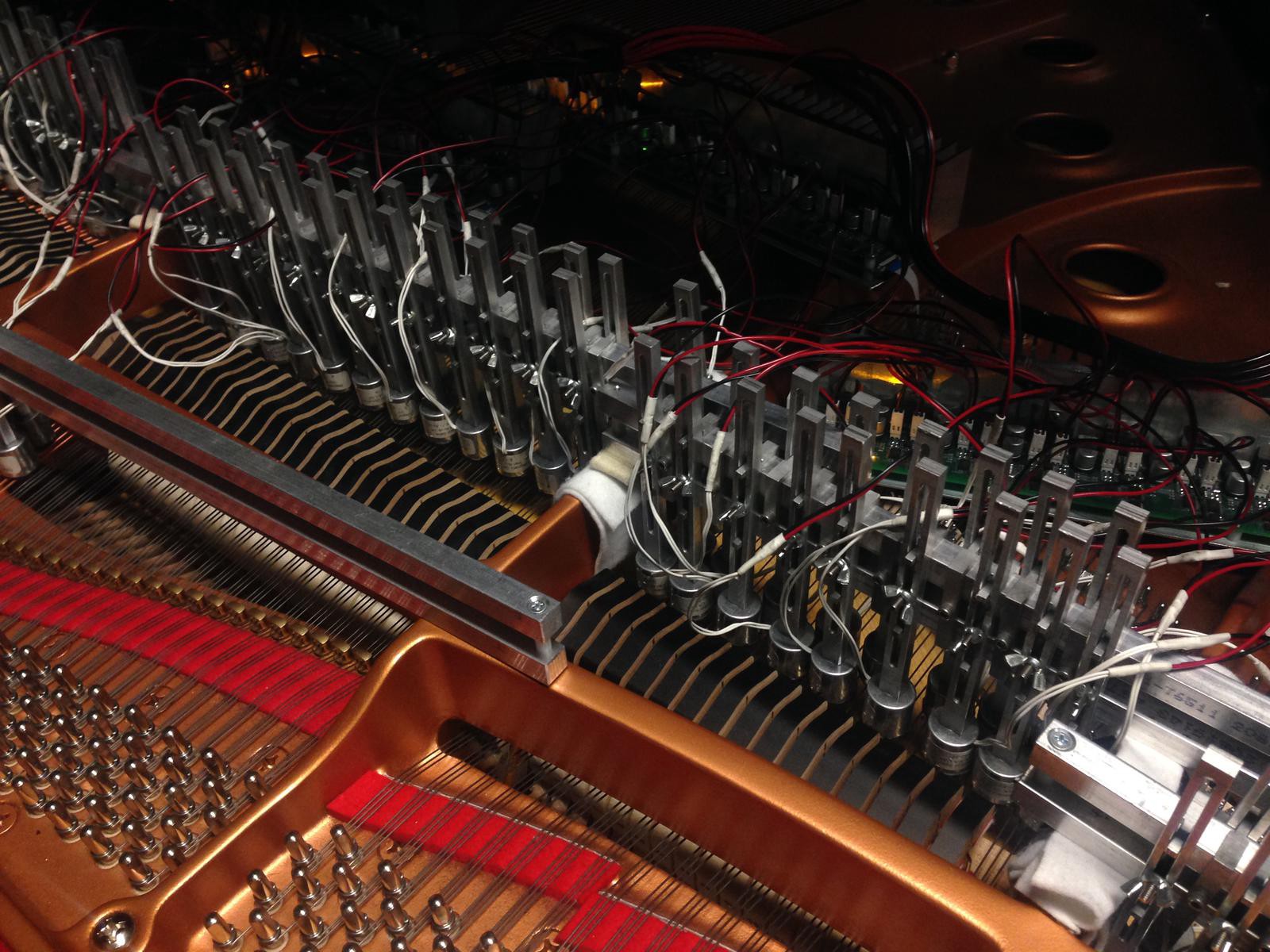

It’s not the first project to try to add something to a piano, but McPherson says he’s offering an inverse of the “prepared piano” approach–which relies on the placement of objects like forks, marbles or paper clips on or between the strings–because those tend to highlight the percussive nature of the instrument. In contrast, McPherson is “exploring the resonance of the strings, entirely independently of the hammer action. It’s pulling out the other half of the piano,” he says.

McPherson is a viola player, not a pianist (as well as a composer and electrical engineer), and in a way he’s bringing string-player techniques to the piano. He describes the setup as a bit like taking a bow to the piano’s strings. Just as you might choose to pluck the strings on a double bass or draw a bow over them, the magnetic resonator piano offers a different way to interact with the inside of a piano.

McPherson built his first version after he finished his Ph.D. in the 2008″”9 academic year and has been working with a range of musicians ever since. It was important to him that the piano was not just a vehicle for his own music, so in 2011 he rebuilt it based on feedback from other uses.

He was looking to respect the training and culture of piano-playing that’s already in place. McPherson wanted an instrument that extends the capabilities of the familiar acoustic piano, while still remaining recognizable. Playing the piano is complicated; people spend years of their life learning the skill, he added. “You can’t tell people to unlearn everything they know about the piano and expect them to go for it. So what I’ve tried to do here is keep as much of the traditional piano as possible, but add to it new techniques, in a way that allows people to bring their expertise to the table,” he said.

McPherson’s also intent on keeping it as an instrument that’s playable and doesn’t use the addition of electronics to take human action out of the equation. There’s loads you can do when you start playing the strings of the piano with magnets–make a crescendo, change the pitch, play different harmonics–but, McPherson says, “I needed a way to control all of this in a way the player could engage with, otherwise it’s just a pile of possibilities. And I didn’t want to pre-program it because it’s not really an instrument in the same way.”

You still play the instrument using its keys. He shows me. The effect is a rich, rather echo-y and slightly spooky noise, not unlike an pipe organ.

Says McPherson, “It’s creating a new tool for composers and performers, but ultimately not replacing the human elements–someone writes a piece and someone plays a piece. But the instrument is capable of a lot more thanks to the addition of this electronic kit. It’s a fusion of electronic and acoustic. It’s not a synth[esizer].”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Fast Forward section, which examines the relationship between music and innovation. Click the logo to read more.