Last week’s newsletter included a link to a Vice profile of Naomi Wu–”the face of China’s cyberpunk city.” That was one of mine. I put it in because, well, how often do you get profiles of Chinese celebrities (even, or especially, the niche ones) in Western media? I read it, thought it was interesting, wrote the link, then moved on.

Over the last week, however, Wu has been trying to get Vice to retract the piece, and Vice has been defending its reporting. I won’t dwell here on the specifics of the disagreement–it includes allegations of doxxing, censorship, endangerment, sexism, breaches of journalistic ethics, and more–and the discussion about this specific issue is easy enough to find on Twitter.

No, I want to talk briefly about something that I’ve seen here, and elsewhere, recently, which journalists seem to be coming up against. It’s to do with Wu saying that the “contract” (a request from Wu that certain topics be off limits in the piece) between her and the Vice reporter, Sarah Emerson, was violated, and that’s in part why she’s so upset. It’s not just the content of the article; it’s a difference in interpretation of how enforceable that “contract” was, and what it represented in terms of the power balance between them.

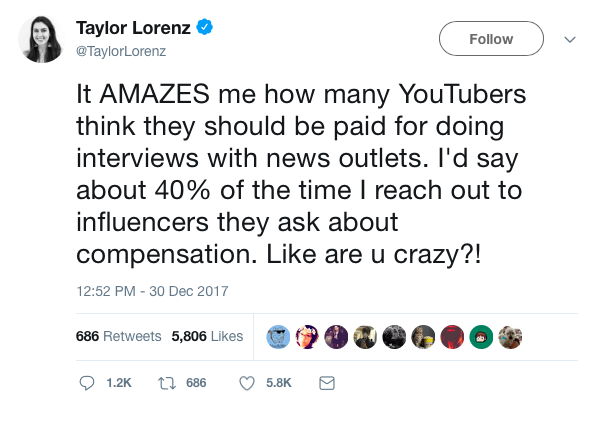

I’d argue it’s the same kind of mentality that Daily Beast tech reporter Taylor Lorenz tweeted about back at the end of 2017:

(She followed it up with an example in a later tweet: “ME: So you just sent out a racist tweet to your 400k followers, I’m doing a story on this, can you offer comment or context?” YOUTUBER: For $5,000.”)

The problem here comes from two worldviews clashing. The reason many people speak to journalists has, traditionally, been because it’s a way to access a platform–for free. You can shape public perception of your work, counter accusations, announce new products, tell a story that you feel is important, etc., etc. At the same time, journalists aren’t meant to pay sources because it creates an incentive for people to say what they think the journalist wants to hear.

Wu was not paid, and did not expect payment, for the Vice piece. But she makes YouTube videos and fans fund her through Patreon, like so many other people trying to make it as self-facilitating media nodes. The disintegration of journalism-as-media-gatekeeper has also eroded that old incentive to speak to a journalist for access to a platform. It’s still there, obviously, but it’s just one option rather than the only option. And the culture of collaboration on platforms like YouTube is very different to that of an interviewer-interviewee one. It’s standard practice on YouTube for creators to cross-promote each other–going on each other’s channels, making something together, growing an audience together. The quid pro quo is more explicit, both in terms of how it’s agreed and how it is about boosting both parties.

It’s never been as easy for one person to become a media entity, someone with as much reach and influence–in the purest, non-marketing-bullshit sense–as a newspaper with a hundred people on staff and a hundred and fifty years of reputation to cash in. There’s an echo here of what’s happened with the gig economy, I suppose–broader economic and political forces acting in tandem with technological innovation to incentivize people into the realization that they are individuals worth something, even if it’s in the most basic of currencies: time for money. Why should someone whose days are spent talking to a camera for money not talk to a journalist for money as well? Where’s the collaboration? Where’s the audience sharing? Where’s the contract?

I’ve been a journalist for a while, but I went to j-school less than a decade ago–the old lessons about paying for sources, and the entitlement that journalists should expect when it comes to accessing people for interviews, were the same as they had been for decades. This is a very new thing, but I doubt it’s going away–especially now children are starting to grow up thinking “professional streamer” is a legitimate vocation. (No judgement intended, either–I watch people playing ludicrously-complicated strategy and simulation games on Twitch all the time.)

I have no idea what might happen if this kind of thing continues to escalate, because, as anyone in media can tell you, we can’t afford to pay everyone we speak to.

(Seriously, please don’t do this to us, us dinosaurs–we are dying.)

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our The Internet section, where we report on the past, present, and future of the information superhighway. Click the logo to read more.